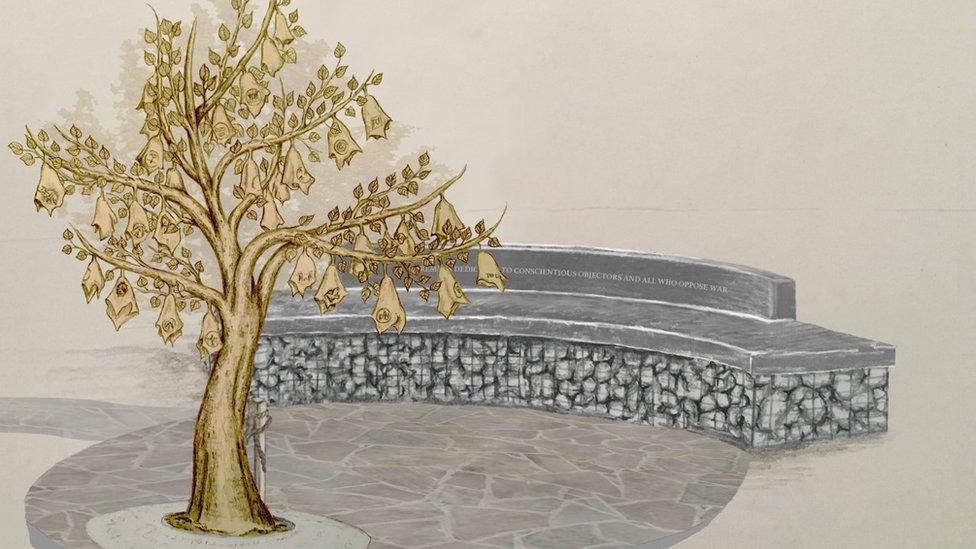

'Remember conscientious objectors too'

- Published

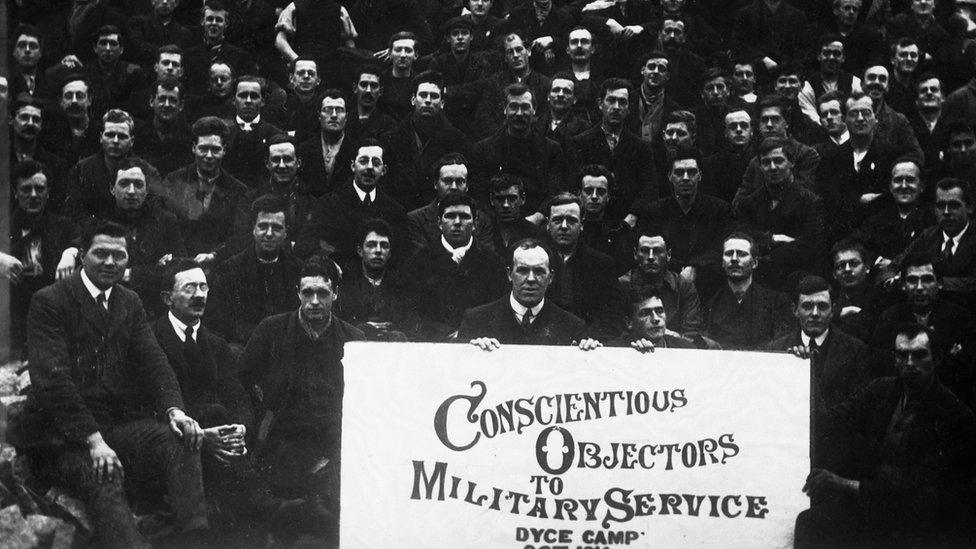

Dyce Camp near Aberdeen was closed following the death of a prisoner

On Sunday there will be reflective silence, heads will bow and buglers will play the Last Post as poppy wreaths are laid. Britain will remember those who did not return from war.

However, we should not forget those who did not go - the conscientious objector, according to Brian Larkin of the Edinburgh Peace and Justice Centre.

"There's wide recognition for remembering the men who died in the many wars, and that's as it should be, but the story of the opposition to war and of conscientious objectors is a very important part of our history, especially in Scotland", he said.

He believes the story of war is not presented accurately, if the opposition to war is not remembered and marked.

"We should remember that there has been a tradition of opposition and refusal to take part in wars - so we can consider what that might mean for us now.

"The first sentiments of remembrance from World War One were that it was 'the war to end all wars' and should never happen again - we need to rekindle that."

Following the Military Service Act in 1916, those who objected to conscription could apply to a local military service tribunal for exemption, making Britain one of the first countries to recognise conscientious objection.

During World War One 1,400 men appeared before tribunals in Scotland.

Tribunal panels were composed of those held highly in society and always included a military representative.

"The role of the military rep was really to make sure anyone who claimed conscientious objection was rejected, they always objected", according to Mr Larkin.

"Objectors were often only allowed to speak a few short sentences.

"In most cases objectors who were recognised were religious - in particular Quakers and Jehovah's Witnesses.

"If there was a political objection, they were rejected and put into the military and faced court martial. They had some horrific experiences - people suffered the consequences of their choice for many years."

According to Mr Larkin many were sent to prison - some up to six times.

Those sent to prison often faced hard labour and enforced silence, with many being force fed during hunger strikes and some thrown into pools of sewage .

The harsh conditions resulted in 73 deaths while imprisoned.

"The first conscientious objector to die in prison was in Dyce Quarry in Aberdeen in 1916, afterwards the government shut that camp.

"It took a great deal of courage and moral fortitude for people to go against the norms. That should be celebrated and recognised."

Mr Larkin also believes it is important to note the contribution many conscientious objectors made to society post-war.

Conscientious objectors

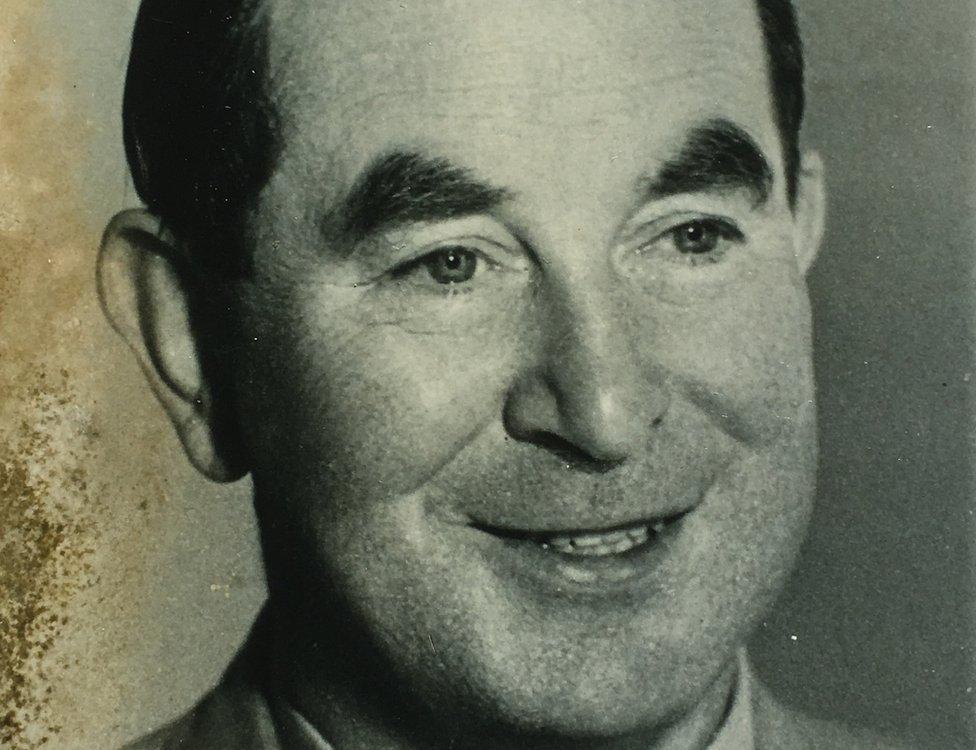

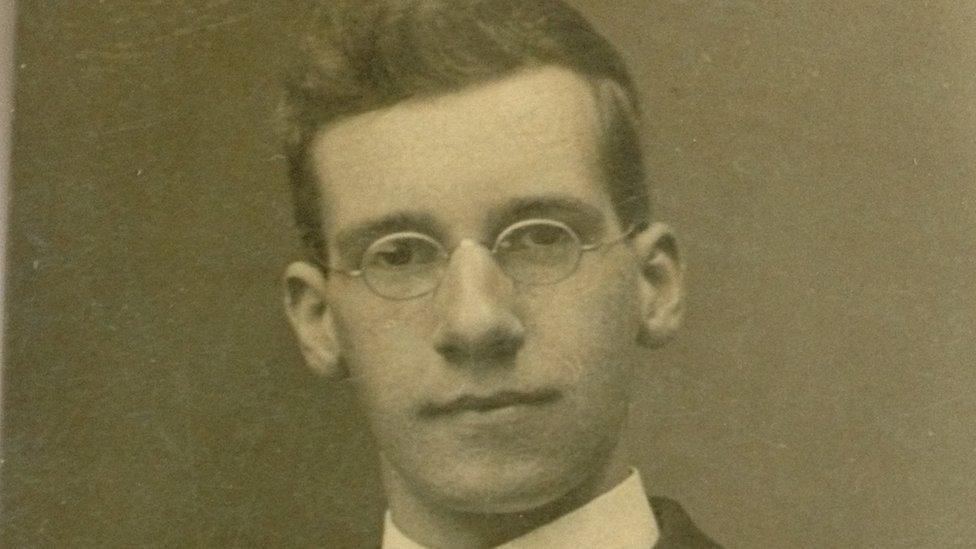

Arthur Woodburn, went from conscientious objector to secretary of state for Scotland.

Born in Edinburgh, he was not always an objector, but his views changed when, while working as a clerk at London Road foundry, he became aware of the arms trade of the time.

Arthur Woodburn became Secretary of State for Scotland after World War Two

When conscription began Mr Woodburn would have been exempt due to his occupation and and a kidney condition. However, he chose to notify authorities of his resistance and became a marked man.

He was imprisoned six times during World War One, including a spell in Calton Hill Gaol, in Edinburgh.

Following the war he rose up political ranks, becoming the MP for Clackmannan and East Stirlingshire for 31 years and joined Clement Atlee's cabinet in 1947.

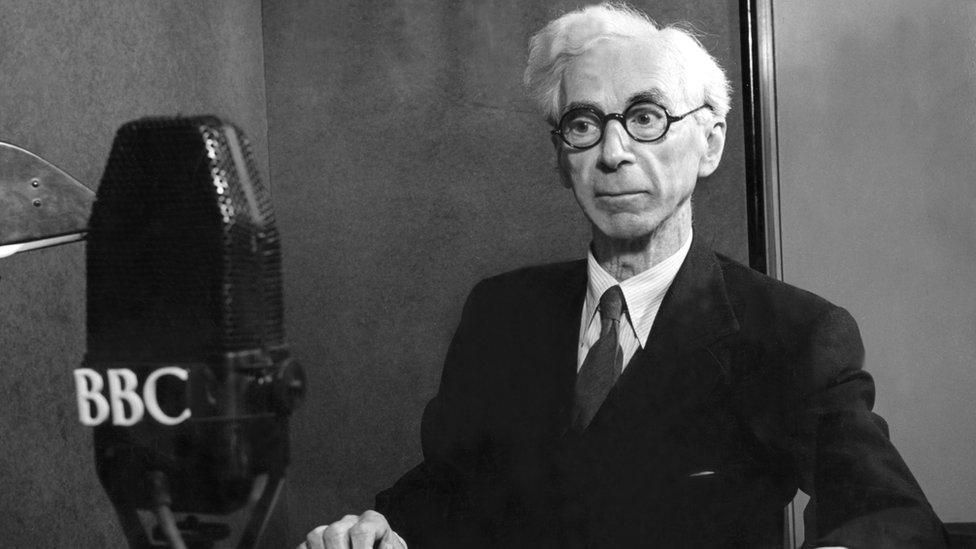

Philosopher Bertand Russell was a founder of the No-Conscription Fellowship, a British pacifist organisation

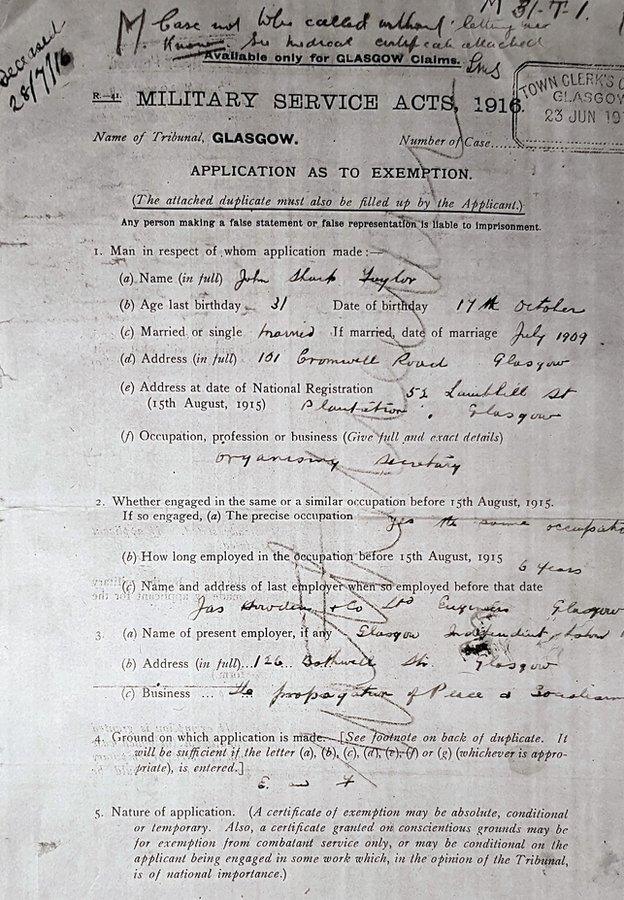

John S Taylor was a Quaker born in Govan, Glasgow, in 1885. He trained as an engineer but as a socialist, he soon turned to politics and was elected to the town council in 1912.

When conscription was introduced he filled in an exemption on conscientious grounds. Under it says, "The propagation of peace and Socialism". It was to be one of his last acts.

Exhausted from touring the country addressing peace rallies, Mr Taylor did not have the strength to survive when poison from a bad tooth found its way into his blood and he died in July 1916.

Recording his death The Govan News said: "The death of Councillor Taylor at an early age reminds us that it is not only at the front that careers are cut short and men of ability cut down before they reach maturity".

John Searson was working as a librarian in the Mitchell Library in Glasgow when he was called to military service.

He was one of the few granted exemption on moral and political grounds and was sent to shovel coal at a power station.

John Searson was eventually allowed to return to work as a librarian

Following the end to the War, Mr Searson reapplied to be a librarian but was unsuccessful. It would be 10 years before he could return to his career - when he did, it was to the basement of the Stirling Library in Glasgow.

When those who survived the battlefields returned home, John Searson, like many other conscientious objectors, had to start again from the very bottom.

- Published18 October 2018

- Published15 May 2018