What have the Vikings ever done for us?

- Published

Sketch of a fleet of Viking ships on a raid

Life as a Viking was never easy.

Days were spent rowing longships, creating intricate art, or telling stories about duels between gods and giants.

Their legacy, however, extends beyond the bloody and gruesome tales that have themselves become legend and synonymous with Viking identity.

What, after all their raids and travel across Europe and the globe, have the Vikings ever done for us?

An example of Thor's hammer Mjollnir, was worn usually as a pendant.

Who were they?

Vikings were peoples from areas of Scandinavia - Denmark, Sweden, and Norway - who planted crops in spring and raided towns overseas in summer.

The Viking Age - when they were most active in their exploration and raiding - covers the period from the 8th Century until the 11th Century AD.

Norse settlers were those from these countries who came following the raids to trade and settle.

The Viking people were adept at using the land - many were farmers, in areas where the climate allowed them to grow crops. It was common to find barley, cabbage and turnips in a Viking larder.

Art was another strong element of Viking identity. According to Davy Cooper of the Shetland Amenity Trust, jewellery had a practical use.

"They displayed their religious affiliation through their jewellery. Many people wore Thor's Hammer," said Mr Cooper.

Associated with a thunderbolt, it was believed that Thor defended the order of the gods against their foes using the might of the hammer.

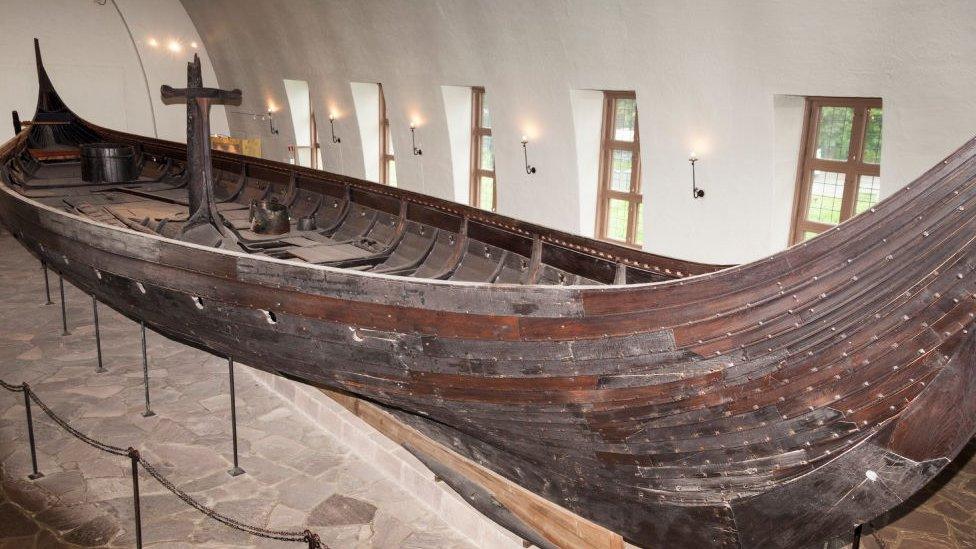

Gokstad Viking ship showcased in the Viking Ship Museum in Norway.

The Viking Expansion

Trade became more varied as the Vikings made their way across Europe, bringing conflict and commerce where they went.

One example was the Volga River in modern-day Russia. The Vikings who settled along the river, who were known as the Rus, gave Russia its name.

The Volga Trade Route opened up Northern Europe to the possibilities and potential of trade with Arabic nations and the Byzantine Empire.

According to Mr Cooper, the items plundered from monasteries along the way "allowed them to buy the things they couldn't produce on their own farms".

These included goods ranging from salt and dyes to spices which were collected in exchange for honey, fur and slaves taken from the Viking raids.

They travelled even further afield, arriving in modern-day North America towards the end of the 10th Century, where they are said to have had fractious relationships with native tribes in North America and Greenland. The Vikings termed them "Skræling", meaning "skin-wearer" or "wretched people".

A depiction of Norsemen landing on the coast of North America in the 11th century

How did they get there?

Viking technology was revolutionary. In particular, the marine technology they developed established them as world leaders, and feared anywhere there was water.

Mr Cooper said: "[Their ships] were designed for speed, to carry the maximum number of men, and to go a fair way up river systems."

He continued: "The shape of the boat meant it created bubbles on the edge of the planks [on the outside of the boat]. To all intents and purposes, a Viking ship rides on a cushion of air, and has far less resistance in water."

And for navigation they had a "sun compass" which was, according to Mr Cooper, "a very simple circle with a pin in the middle" which is used to take a reading according to the height of the sun and time of day.

But journeys sometimes had unexpected final destinations.

"They tended to get blown places accidentally, but they knew what direction to sail going back," said Mr Cooper. "That meant they could find the place again, and they could tell someone else how to find it."

Having used the natural world to provide food, the Vikings were able to utilise it in a novel way for navigation - in the form of crystals.

Mr Cooper said: "They used a crystal that, when turned in a certain direction it goes dark, and when it goes in another direction it goes light. So when turned to a light source they discovered that it even worked in fog if they knew where the sun was - meaning they could figure out what direction they were travelling in."

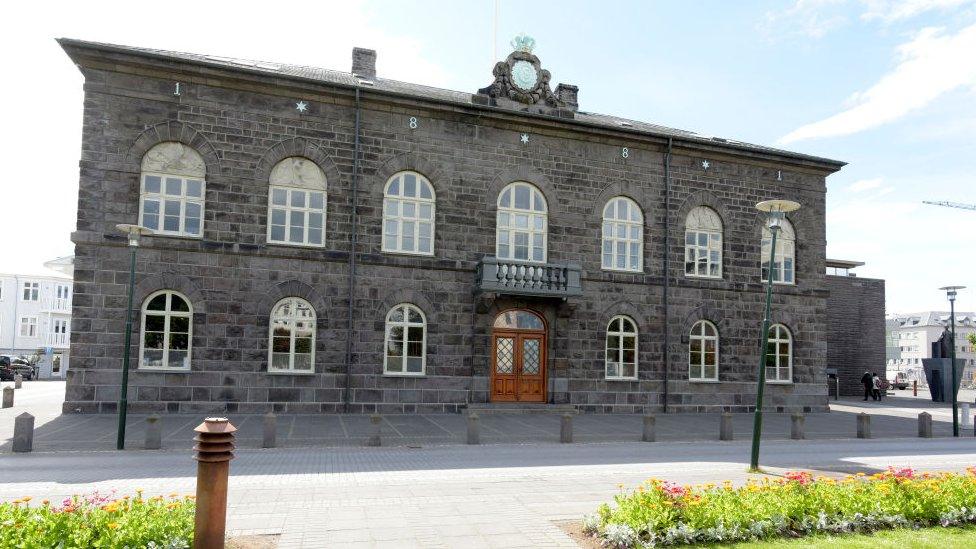

The Althing, the parliament in Reykjavik, originally established by Vikings in 930AD

Doing their 'Thing'

Viking society has been influential on modern life in numerous ways.

Art and language derived from Viking cultures is still evident literally in the day-to-day - 'Thursday' itself comes from 'Thor', the Norse god of thunder.

The Viking system of law contains elements which mirror the ethical codes of many cultures, along with a framework of ownership.

Mr Cooper explained: "They are still some of the laws we use to this day; don't kill, don't steal. A lot of it related to property and respecting property."

This loose set of guidelines and rudimentary laws were discussed at a gathering known as the Thing.

At these, alleged criminals would be tried by a group of their peers and could be found innocent or guilty. If the latter was the final decision, people could be fined, semi-outlawed, or fully outlawed.

In 930 AD, Vikings had established the 'Althing' in Iceland. It runs to this day, and is reported to be the world's longest running parliament.

The thing has left a mark on local communities, their names being derived from these gatherings.

Tingwall in Shetland was the site of the islands' local government until the 1500s.

Another prominent location is Dingwall in the Highlands. Archaeological evidence was found in 2013 confirming it was the site of a Viking parliament, built on the instructions of a powerful Viking earl.

Mr Cooper said: "The Viking system was almost like our current system still works. There was a local Thing, which was a local council. Then there was like, for example, a Shetland-wide Thing. Local Things would send representatives to that. Ultimately there was the King and court in Norway."

Icelandic Women's brooches, ornamented similarly to that from Viking Age Scandinavia.

In ways, this structure filtered through into egalitarian aspects of Viking society.

Mr Cooper said: "Women had rights in Viking times that they lost and didn't regain for 10 centuries. They could own land, they could inherit land, and they could speak at the Things.

"They were a fair-minded race. Despite their reputation. they had rules to live by.

"It's just that those rules didn't apply to anyone who wasn't a Viking."

- Published18 February 2018