The female shipbuilder cast aside after the war

- Published

Janet Harvey is finally being recognised for her work in the shipyards during the war

Janet Harvey worked on some of the biggest battleships built during World War Two but when the conflict was over she was "cast aside" as the men took over once again.

She is now 96 and her memory of her wartime service as an electrician in the Clydeside shipyards has faded a little.

But she remembers clearly the reaction of the men when she first walked into the yards as an 18-year-old in 1940.

"It was horrendous," she says.

"It was awful. All the men were looking at us and whistling.

"It gradually quietened down and you got used to it but it wasn't an environment for young girls."

Janet (bottom right) was one of seven women working on shipbuilding in the yards

Before the war, the shipyards of the Upper Clyde had been almost exclusively male.

Jobs such as welders and electricians were not done by women.

"Women weren't in that industry at all," Janet says. "The men would have objected, actually."

But with so many skilled male workers away overseas, women were drafted in to boost numbers as Britain tried to bolster its naval fleet.

The Royal Navy 'fast battleship' HMS Vanguard was one of the ships Janet worked on

Janet was just 18 when she got a letter telling her to register for war work.

She was given the choice of welding, joining the land army or becoming an electrician.

Janet has been working in a shop since she was 14 and did not really fancy any of them but decided to be a "spark".

She did three months training at college before she donned an ill-fitting navy-blue boiler suit and started work at the Fairfield shipyard in Govan, which was then owned by Harland and Wolff.

Solid friendship

Before long she transferred to John Brown's shipyard in Clydebank, where she worked wiring up the electrics in the cabins of battleships.

She says there were just five female electricians and two female welders among thousands of men.

The woman stuck together and struck up a solid friendship.

"We were very close," she says.

Three of the women were a few years older than Janet and they tried to protect her and make her feel comfortable, she says.

Before the war shipbuilding was an almost exclusively male environment

As well as the constant wolf-whistling from the men, Janet says she had to endure long, tiring days in which she set off from home at 06:30, often after spending the night in the air raid shelter during the Blitz.

"A lot of time you did not get any sleep and you still had to go to your work in the morning," she says.

"You couldn't stay off. You had to be really ill to stay off your work."

The shipyards of the Clyde were targets for the German bombers and Clydebank was devastated by bombing in 1941.

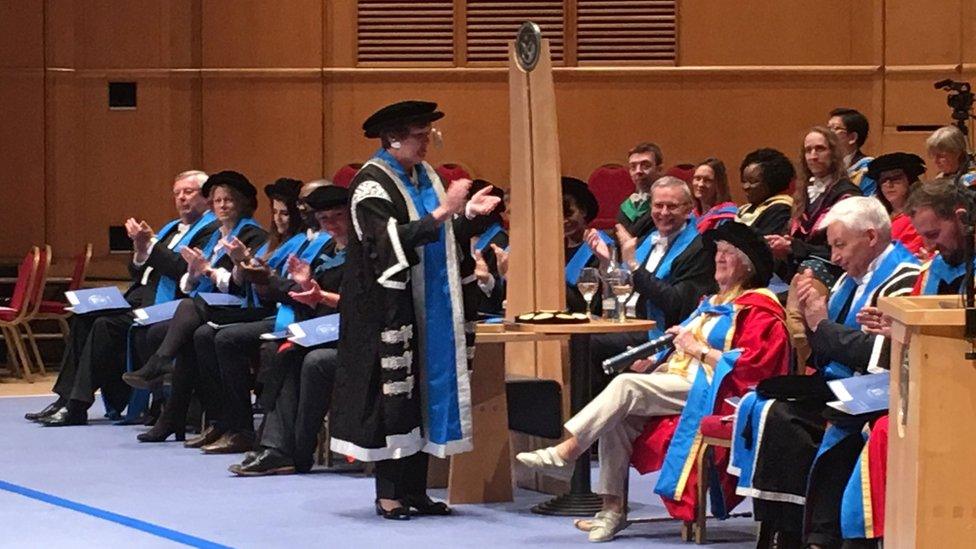

Janet received an honorary doctorate from Glasgow Caledonian University

Janet says she did not worry about the bombs during daylight and tried to concentrate on doing a good job.

The biggest project she worked on was HMS Vanguard, the largest and fastest of the Royal Navy's battleships, which was only finally finished after the war was over.

She says the construction of the massive warship was "hush, hush" and she was told not to discuss it with anyone.

But one of the highlights of her six years in the shipyards was when the crew came to take over the Vanguard and thanked everyone who had worked on it.

She says she felt a great pride and achievement when the officers congratulated her.

'Let down'

However, almost exactly a year after the war was over the emergency government order that had taken her into the shipyards was rescinded and Janet's career came to an abrupt end.

She was immediately made redundant.

"We felt let down," she says.

"They did not give us time to pull ourselves together. There was not even a letter to say you did a good job."

Janet Harvey is finally being recognised for her work in the shipyards during the war

Although she had found the shipyard experience difficult and had often been counting the days until it ended, she felt "cast aside" by the way it finished, she says.

There was no recognition of the contribution that she and the other women had made to the war effort.

"We were proud of what we did," she says.

"We thought we did a good job."

On Tuesday, Janet's service was finally recognised when she was awarded an honorary doctorate of engineering from Glasgow Caledonian University "in recognition of her outstanding contribution to the war effort with the Glasgow shipyards".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Janet says it is quite a surprise to get such recognition seven decades later.

"I'm quite thrilled," she says. "It's taken a long while.

"What took them so long?"

After the war, Janet did not continue her career as an electrician because even outside the shipyard it was a trade that had very few women.

Instead she returned to shop work but she says she was always handy around the house when it came wiring plugs or changing fuses.

And although she says she is too old to do any wiring now, she still has the original hammer and pliers from her shipyard toolbox.

They are a souvenir of six years of war effort and sacrifice that are finally being recognised.