The Glasgow man who sketched the ultrasound machine

- Published

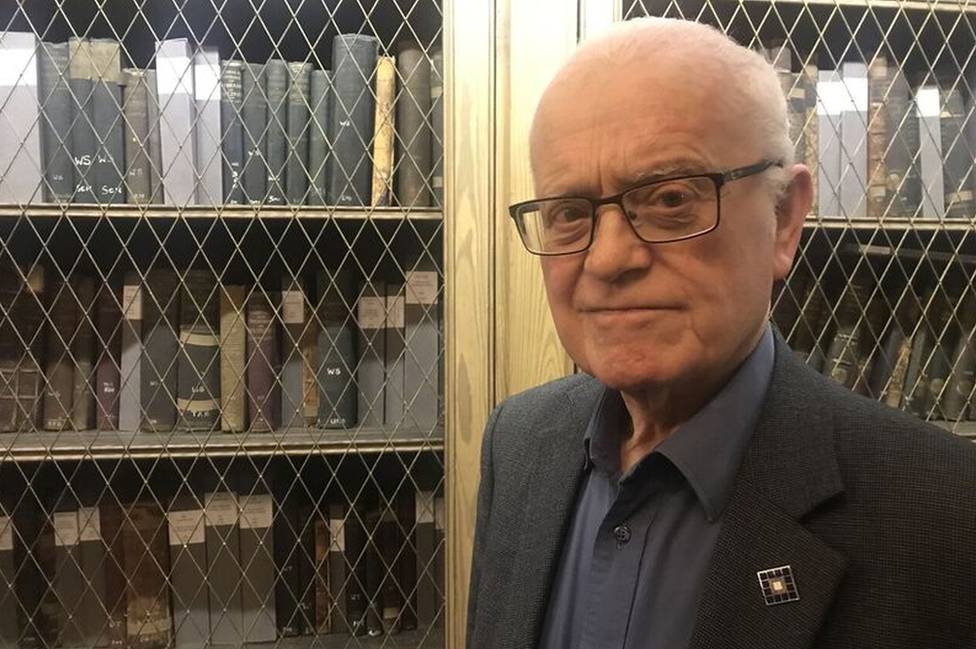

Professor Dugald Cameron is the man responsible for the early sketches of the ultrasound machine used in pregnancy scans

Going for an ultrasound is a common and routine part of most women's pregnancy.

The scans can examine mother and baby's health, as well as detecting any abnormalities early on in pregnancy.

However, it is little known that the idea, and indeed the machine, were both pioneered and built in Glasgow.

Ground-breaking

For a few short years in the late 50s and early 60s Glasgow led the world in its research and implementation of ultrasound and its medical uses.

2018 marks the 60th anniversary of the first paper to be published highlighting to the medical world the possibilities of ultrasound.

It was a unique and ground-breaking collaboration between experts in clinical obstetrics, engineering, electronics and industrial design, who created the first prototypes and production models of ultrasound scanners for routine obstetrics scanning in Glasgow hospitals.

At the heart of this was a young industrial designer from Glasgow, Dugald Cameron.

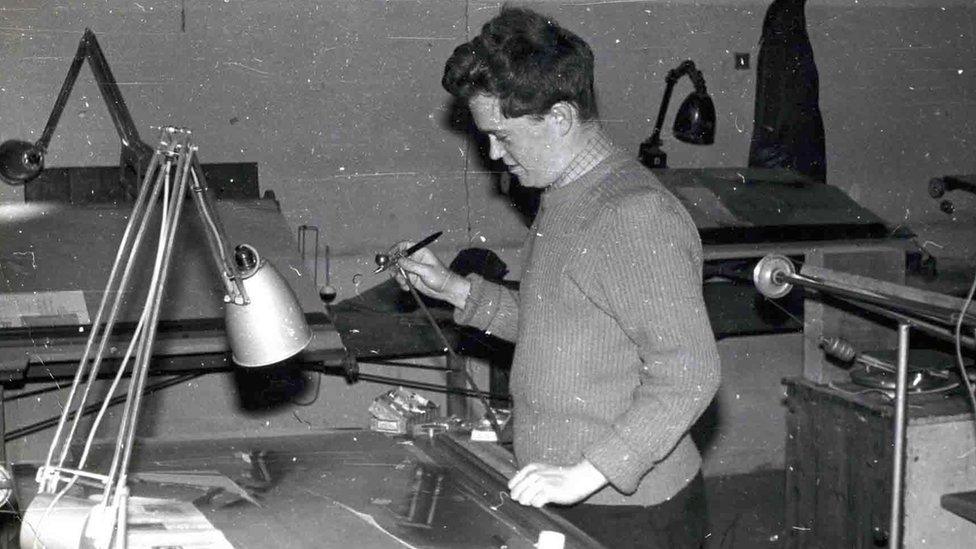

A young Dugald Cameron at work in his studio

"A student in the year below told me what work her brother-in-law, Tom Brown, was doing," Cameron explains. "My initial involvement began as a commission to make a drawing of a proposed unit."

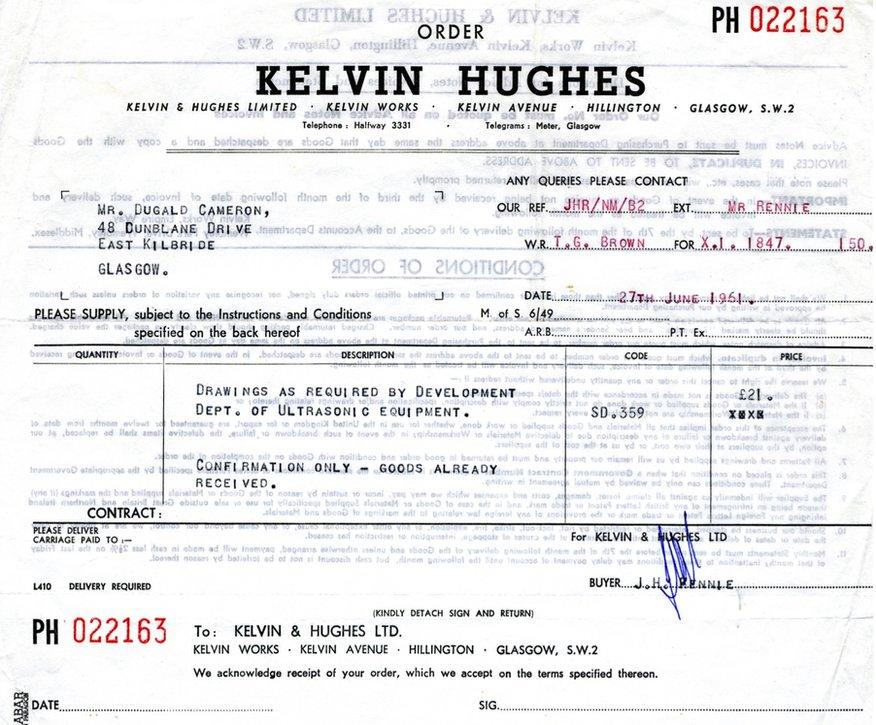

Tom Brown was a young engineer who worked for Prof Ian Donald at Glasgow-based firm Kelvin Hughes. Together with Dr John MacVicar, the three published their findings in the 1958 Lancet paper Investigation of Abdominal Masses by Pulsed Ultrasound.

"As a final year student I had persuaded Tom Brown to reconsider the design to facilitate its use by both medics and patients.

"The first outline drawings were done lying on the floor in Tom's flat and progressed in the industrial design studio in the east end basement of the Glasgow School of Art's Mackintosh Building.

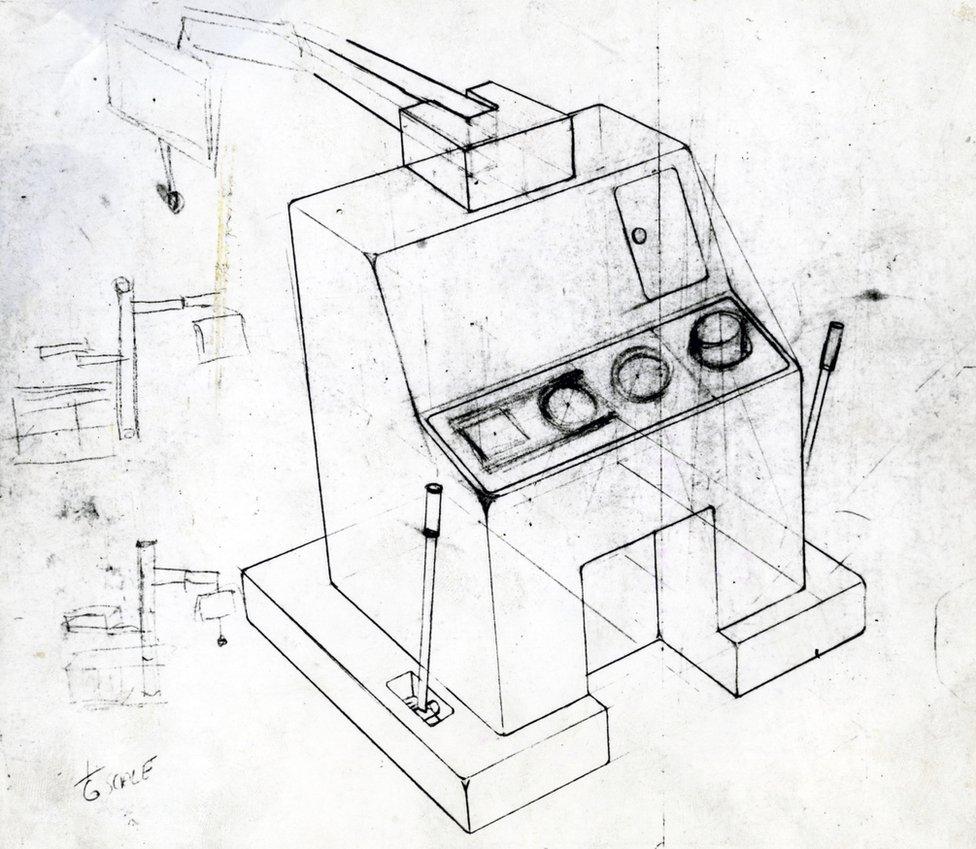

Professor Cameron's early sketches lead to what has now become an integral part of any woman's pregnancy

"I persuaded Tom to do another different arrangement because I felt the way it was coming out looked like a gun turret. This was no way to face a pregnant woman!

"I said to him 'We can do better than that'.

"The outcome of the redraw was the Lund Machine, and from this we went on to design the Diasonograph in 1965. This was the first ultrasound machine to go into service.

Cameron was paid £21 for his drawings of the ultrasound machine in June of 1961

"Ultrasound had been used for other things during the war, but Donald was the one who had the idea to use it for obstetrics and gynaecology.

"Unlike other attempts at medical ultrasound, the Glasgow experiments worked very well."

However, Glasgow was not in the forefront of this ground-breaking technology for long.

"Unfortunately in the 1960s the company which had made the original Diasonograph machines withdrew the product and the technology went on to be developed elsewhere," he says.

"It's one of these sad stories that should have meant a lot to Glasgow in terms of replacing the old industries with the new, but in fact didn't."

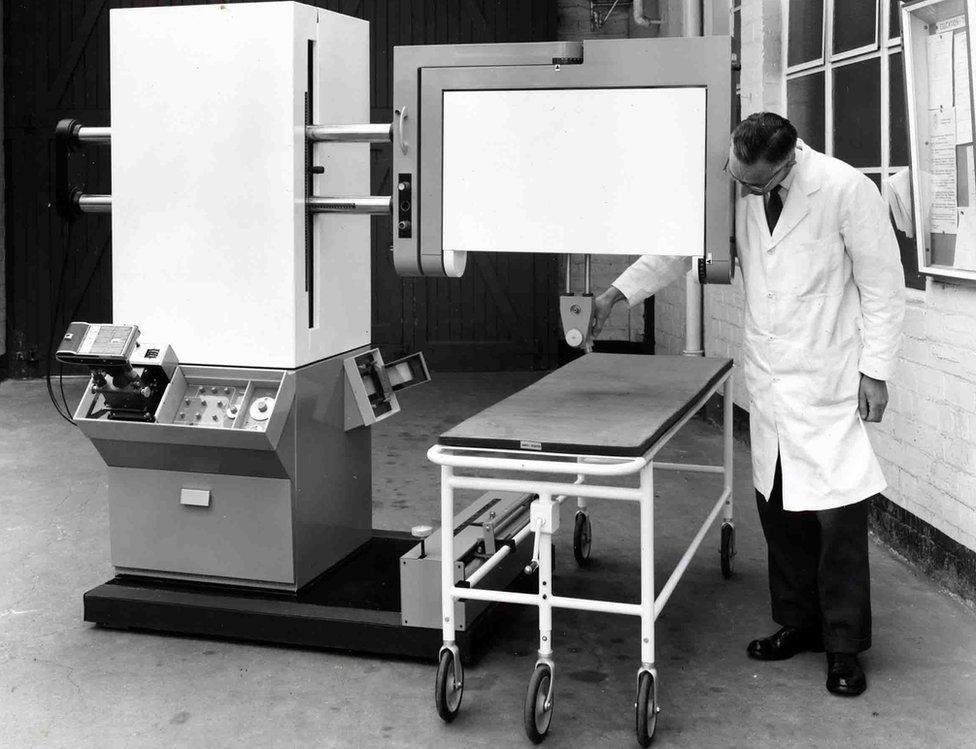

The Diasonograph, the first ever ultrasound scanner for use in obstetrics

Prof Cameron describes his frustration at the lack of recognition that Glasgow's efforts have received over such a world-changing invention: "This particular technology is used internationally," he explains.

"Almost every pregnant woman will have at least one scan, and it will be good news for her usually."

The development of ultrasonics for obstetrics were pioneered by Prof Ian Donald of Glasgow University and the development of the product owed much to the engineers working for Glasgow-based firm Kelvin Hughes, particularly Tom Brown.

"The city should take pride in this," says Prof Cameron.

"At least Glasgow has retained the prototype scanners," he adds. "The original one is in the Hunterian but, frankly, no-one seems to give a damn about it."

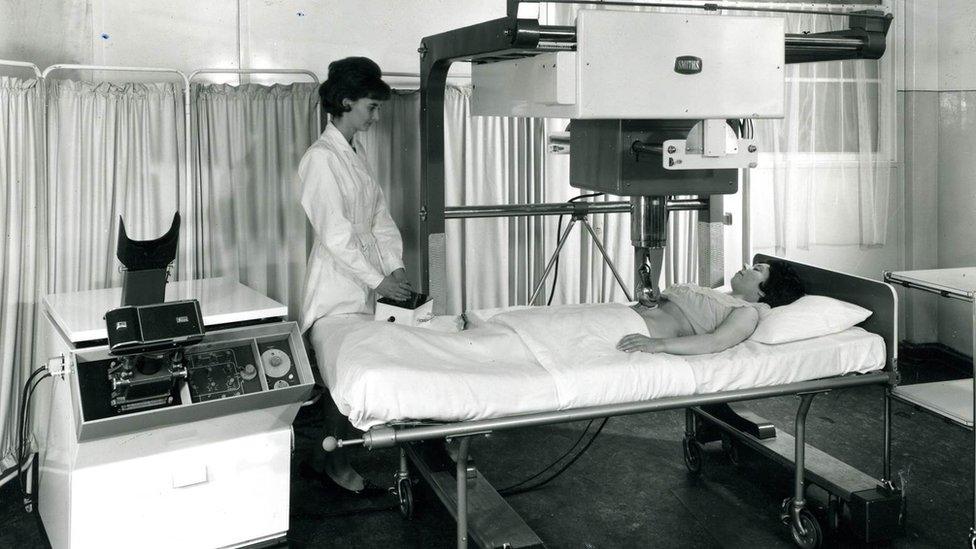

An early Diasonograph at work

In Prof Dugald's time at the Art School, the industrial design class was in the basement in the Mackintosh Building, whose future is uncertain after being hit with a fire for the second time.

"We worked between the studio and the workshop. You could be thinking of something and doodling it on your drawing board, and then you can go into the workshop, get a bit of wood, and make a model of it," Mr Cameron explains.

"It's a great way of doing things."

When asked about the Mackintosh Building, Prof Cameron's belief in the School was clear: "Only one thing comes to mind when I think of the Mackintosh Building, and that is 'resurgam' meaning, 'I will rise again', and again and again and again."

Cameron worked on the sketches in the basement of the east end of the Mackintosh Building

Prof Cameron has fond memories of his time at the Art School: "We had a great teacher of the general course called William Drummond Bone. He was a marvellous man; quiet and unassuming. He taught me the discipline of drawing.

"We did it every day. In fact I draw most days even now, have done so since I was a wee boy.

"It's a joy to do. It's a way that a designer gets to talk to himself. Drawing, really, is the basic language of creation."

Take in December 1958, Cameron (far left) with his classmates and teacher, William Drummond Bone (bottom, third from right)

Prof Cameron went on to become Director of the Glasgow School of Art in 1991 until 1999, after studying there in previous years.

Shortly after his time as director, he was appointed as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2000 New Year Honours "for services to Art and Design".

He, together with his former student Alastair MacDonald amongst others, set up the acclaimed Product Design Engineering (PDE) programme, which is jointly delivered by The Glasgow School of Art and Glasgow University.

Professor Cameron now combines his talent for drawing with his passion for flying

Current PDE students now look at what future innovations there could be in this important part of every expectant mum's pregnancy.

Prof Cameron recently gave a lecture at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow, in which he told his story of the ground-breaking invention, as well as imparting many words of wisdom.

"My firm belief that what the world needs is enthusiasm, eccentricity, and excellence," Cameron stated.

A young Dugald with fellow student Elsa Stevens, who introduced Dugald to her brother-in-law, Tom Brown

"Enthusiasm will get you through anything, eccentricity means you won't accept a conventional wisdom, and excellence is what we should always strive for.

"What Glasgow made is what made Glasgow.

"The decline of traditional industries was always inevitable. What Glasgow as a city produces now, is knowledge.

"Knowledge is what we make now, and it can be transported all over the world.

"We should be so proud of that, and make much of it."

- Published19 March 2017

- Published6 September 2017