Rats 'wrongly blamed' for 1900 Glasgow plague outbreak

- Published

The initial cases broke out amid the crowded and unsanitary tenements of the Gorbals

New research has finally established the cause of a plague outbreak in Glasgow almost 120 years ago.

A team at the University of Oslo said rats were wrongly blamed and the real culprits were humans.

Plague hit Glasgow in August 1900, with the initial cases amid the crowded and unsanitary tenements of the Gorbals.

The outbreak was part of the Third Plague Pandemic, which had begun in 1855 and was not declared over until 1960.

Got off lightly

The first pandemic was the Plague of Justinian and the second was the Black Death in the 1300s.

The Third Pandemic killed millions of people, most of them in China and India.

By those terrible standards Glasgow got off relatively lightly with 35 people infected and 16 killed.

Glasgow took drastic measures to halt the spread of the plague

Drastic measures were employed to halt the outbreak.

There were calls for trams, ferries, even coins to be disinfected and hundreds of rats were killed by a small army of exterminators.

Killing rats was a fashionable solution at the time.

'Parasites of mankind'

Just two years earlier the French researcher Paul-Louis Simond had shown how fleas from rats could transmit the plague bacillus Yersinia pestis.

Glasgow's public health authorities had their doubts and suspected people, not rodents, were transmitting it.

They found no evidence of plague in the rat population, concluding the disease might have been spread directly between humans, possibly by what they near-poetically described as "the suctorial parasites of mankind".

Now 119 years later the Oslo study, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, concludes the infection was indeed spread by human-to-human contact.

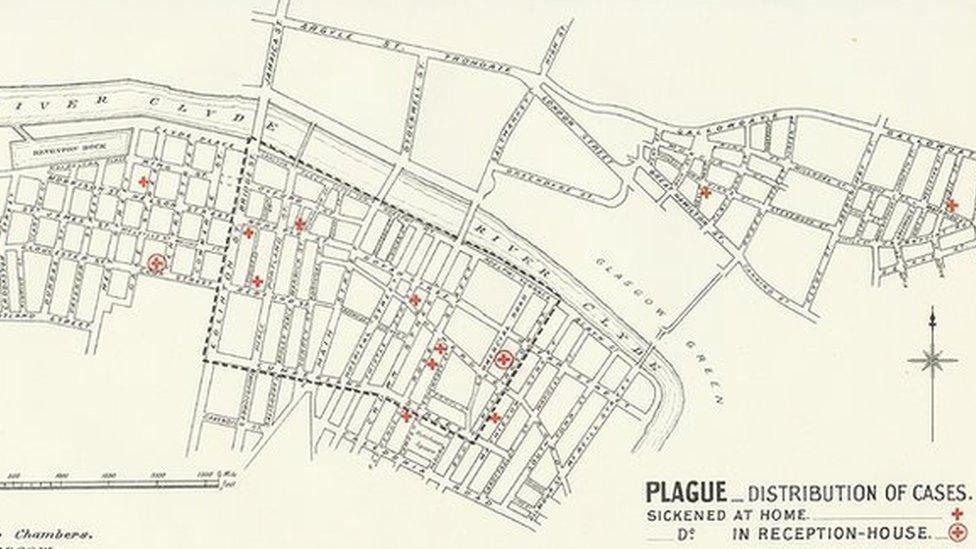

Map showing the distribution of plague cases in Glasgow in 1900

Lead author Katharine Dean and her colleagues, from the university's Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis, said they were able to reach their conclusion thanks to the meticulous records kept by the sanitary authorities at the time.

Back in 1900 the authorities had noted that nearly all of the cases could be linked by contact with a previous one.

Despite trapping hundreds of rats, which were plentiful in the slums, they found no evidence of a rodent outbreak.

Day Zero

The city's medical officer of health had immediately opened an investigation into the spread of the disease.

It established 3 August 1900 as Day Zero, noting that was when "Mrs B, a fish hawker", had become the first to fall ill, along with her granddaughter.

The authorities then searched for people linked with Mrs B or who had attended her funeral wake.

This led to the quarantining of more than 100 people in a "reception house" for observation.

With the support of the Catholic church, wakes following plague deaths were banned.

The new investigation used modern methods to expand on the historic data, finding a high rate of secondary infections within households.

The incubation period for each infection also pointed to transmission from person to person.

The authors said their results gave an important insight into the epidemiology of a bubonic plague outbreak during the Third Pandemic in Europe.

It also confirmed what officials had suspected all those years ago: Glasgow's rats got a bad rap.

- Published31 August 2013