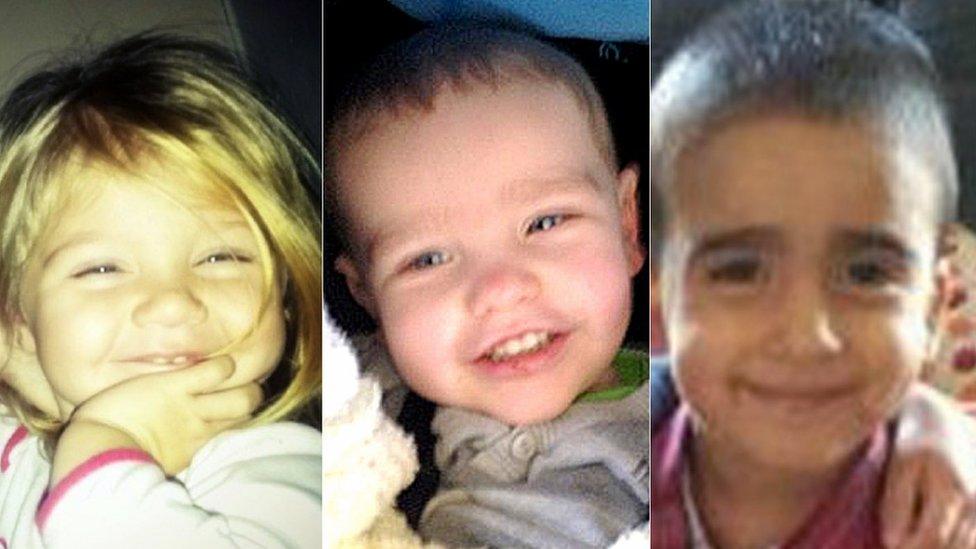

How toddler Lauren died of neglect

- Published

Lauren Wade was just two when she died in 2015

Lauren Wade was just two years and five months old when she was found emaciated, malnourished and unresponsive on the couch of her home in a north Glasgow flat.

The toddler showed no obvious signs of injury or natural disease but she was filthy, with a severe head lice infestation that had spread to her face and chest.

She was extremely thin, with her shoulders, ribs and backbone being "very visible" through her skin.

The palms of her hands showed black dirt in the creases and the soles of her feet were also blackened.

A toxicology report after her death in March 2015 showed the presence of alcohol and diazepam in her body.

Lauren's baby teeth were already showing signs of decay and there was evidence of severe nutritional deficiencies.

Margaret Wade and Marie Sweeney were convicted of the wilful ill-treatment and neglect of Lauren

Last month her biological mother Margaret Wade and her partner Marie Sweeney were convicted of the wilful ill-treatment and neglect of Lauren.

On Friday, they were both sentenced to six years and four months in prison.

The neglect of the toddler and two other children led to a Significant Case Review looking at how the health and social care agencies dealt with Lauren and her parents.

Lack of professional curiosity

According to Colin Anderson, the independent chair of Glasgow's Child Protection Committee, Margaret Wade and Marie Sweeney were uniquely cruel and "devious" in the way they avoided what they saw as "interference" from outside agencies such as health visitors and social workers.

However, he said that the case review showed there had been a lack of "professional curiosity" from those tasked with protecting young Lauren.

Lauren Wade had not been seen by health or social care for eight months

Mr Anderson said a large number of professionals had been in contact with the family but they had not pushed hard enough to see real evidence of improvement.

The case review says the thresholds used to determine what was acceptable in the care of children were too high in this case.

It said the flats where they lived were in Sighthill, an area of multiple deprivation, and the view had been taken that the mother, who was largely dependent on state benefits, was doing her best in difficult circumstances.

However, the flat in which Lauren lived with her parents was described as "uninhabitable" by the police officer who attended the scene on the day she died in March 2015.

Margaret Wade had been thought to have been a single mother

Rubbish dating back two years

There was rubbish strewn all over the flat and it was impossible to gain entry to the kitchen because the bin bags were piled up to waist height.

The bags contained food and rubbish dating back two years.

The couch where Lauren slept was so badly infested with head lice it had a large hole in it and had partially disintegrated.

Two other children in the house were also infested with head lice, were filthy and had strong body odour.

Significant Case Reviews

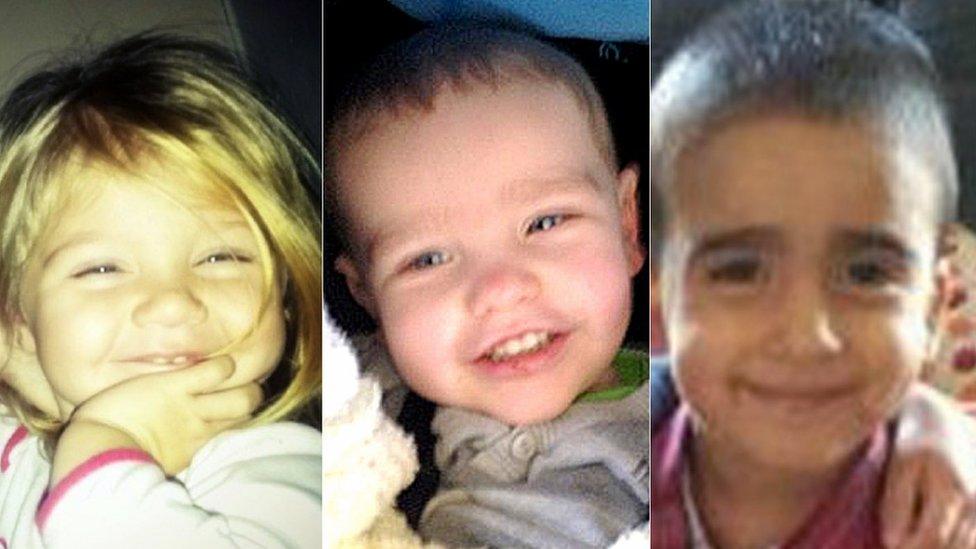

Madison Horn, Liam Fee and Mikaeel Kular all died in Fife in 2014

A review is commissioned when a child in the community has died or experienced significant risk or harm.

Fife Council had three high-profile reviews after deaths at the start of 2014.

In January 2014, three-year-old Mikaeel Kular was killed by his mother Rosdeep Adekoya, who had initially reported him missing. She was convicted of culpable homicide.

Liam Fee was murdered in Thornton near Glenrothes in March 2014 by his mother Rachel Fee and her partner Nyomi Fee.

Just a month later, only 10 miles away, two-year-old Madison Horn was killed by her mother's new boyfriend, Kevin Park.

The Significant Case Review reported in February 2016 but has not previously been made available because of the ongoing court case against the parents.

It concluded that the agencies involved "did not have an accurate, shared understanding of the family's circumstances and that many aspects of the case remained unclear".

'Struggling to cope'

Margaret Wade was 34 when her daughter died and Marie Sweeney was 33.

The review said that before Lauren's death the health, education and social work services thought that Margaret Wade was a single mother and they saw her as "caring but struggling to cope".

Marie Sweeney had been Margaret Wade's partner for 14 years

It was only during the police investigation that it was discovered she had actually been living with her partner for about 14 years.

The review said health staff had no awareness of Ms Sweeney as her partner and they did not know why she had withheld this information.

Reaching milestones

According to the Significant Case Review, Lauren was seen 13 times by health and family teams.

There were eight home visits, six in the first six weeks after she was born on 8 October 2012.

In these early visits she appeared to be gaining weight and reaching developmental milestones.

However, the month after her birth there were concerns from school about the hygiene of other children living in the house.

A series of home visits resulted in an improvement, the report said.

In February 2013 a health visitor said Lauren was still achieving milestones.

She said the house was reasonably clean but scantily furnished and in a poor state of repair.

The following month, when Lauren was five months old, she was formally assessed as not at risk and did not need additional support.

The next planned review was when Lauren was 30 months old. She died weeks before that review in March 2015.

Referral to social work

Concerns about the hygiene of other children in the house led to a health visitor raising serious concerns about the living conditions.

When a visit was arranged with social work a "significant improvement" was noted in the condition of the house.

There were further contacts with the health staff about head lice and diarrhoea but Lauren was last seen by a health visitor in July 2014, more than eight months before she died.

The review said there was no evidence anyone outside the family saw Lauren during those months.

'Key missed opportunity'

The Significant Case Review said it could find no explanation for the extent of the neglect Lauren must have suffered over her final eight months.

It said the lack of reassessment of Lauren's home conditions in June/July 2014 was the "key missed opportunity".

The review said social workers should have made a broader assessment of the home circumstances, but instead were led by the health and hygiene issues such as head lice.

According to the review there were a number of indications of neglect over a period of time but the child was not at the centre of the assessment process.

'A unique case'

Mr Anderson said the parents had not engaged with care agencies but had gone to great lengths to appear as if they were.

The chair of Glasgow's Child Protection Committee said: "At different stages it was clear they had made an effort to tidy the house and that led the workers to assume the situation had improved.

"There are key issues about workers not being sufficiently nosy or using professional curiosity to challenge some of the assumptions especially around self-reporting and self-assessment of parents - not pushing hard enough to find real evidence."

Colin Anderson believes child welfare workers need to "own" the concerns they have about a youngster's well-being

Mr Anderson added: "I've been around social work for almost 50 years and this case is unique in my professional experience.

"The devious ways in which the parents covered up some of the issues around Lauren's care and the way they tried to subvert professional involvement in the case is unique in my experience."

He said workers in child protection needed to "own" the concerns they have about a youngster's well-being.

Mr Anderson said lessons would be learned from the case.

He said: "It is about empowering workers to have more professional curiosity, to demand evidence of alleged improvements in a child's well-being and to follow up on their professional instincts and to challenge other professionals."

He said they should not fall into the trap of passing concerns on to others, but should "own these concerns until they are satisfied that the child's welfare and the child's safeguarding needs have been met".

- Published18 January 2019

- Published21 December 2018

- Published20 December 2018

- Published5 August 2017