Why do patients get ill with hospital-acquired infections?

- Published

In recent weeks the deaths of four patients at Glasgow hospitals - three of them babies or children - have been linked with infections picked up during their stay. So how big a danger are hospital-acquired infections?

Why do people pick up new illnesses in hospital?

By their very nature, hospitals are places with high concentrations of people who are unwell. Many of them have already picked up infections in the wider community.

Bacteria, viruses and fungi are constantly being brought into hospitals by patients, visitors and staff. The challenge for healthcare workers is how to stop these multiplying and spreading.

A complicating factor is that hospital patients often have weakened immune systems and are less well able to fight off disease.

What caused the fatal infections in Glasgow?

The Cryptococcus infection at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital is linked to pigeon droppings

Two patients who died recently at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital - a 10-year-old boy and a 73-year-old woman - were infected with Cryptococcus - a yeast-like fungal infection. The most common form in humans is linked to pigeon or other bird droppings. It is thought it entered the hospital's ventilation system after birds got into a machine room near the roof.

Another patient became seriously ill in a separate Mucor infection. It's a type of mould, commonly found in soil or rotting organic material such as food. Infection is usually caused by breathing in spores. In this instance, a water leak in the patient's room is thought to have been the source.

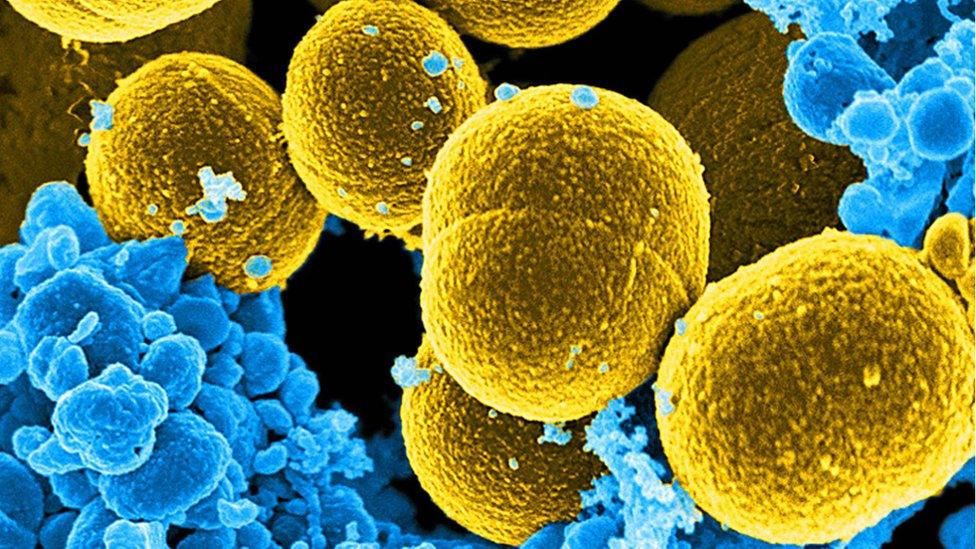

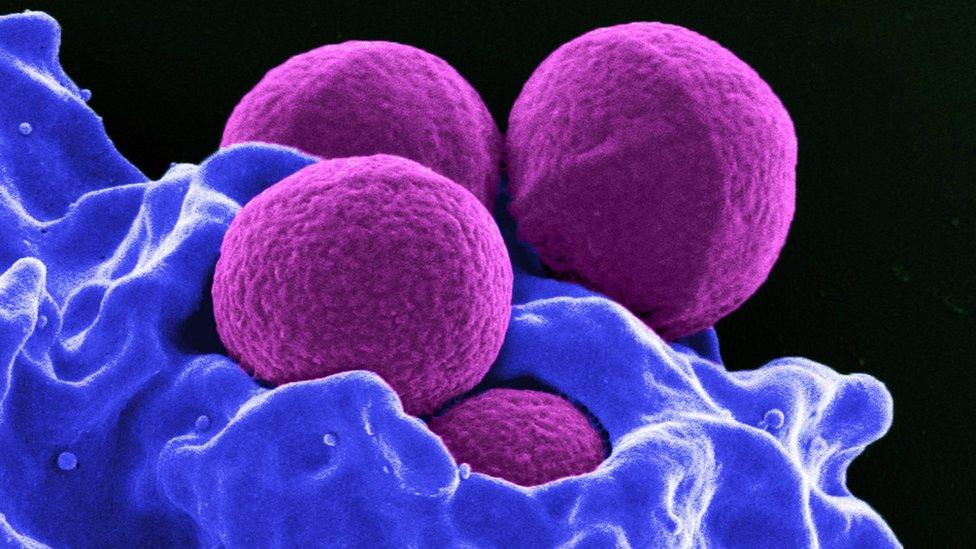

Two premature babies died and a third became seriously ill at the Princess Royal Maternity Hospital. They were infected with the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus.

It's a common bacteria - about a third of us have it on our skin and it's usually harmless. But these "staph" infections as they're known can become serious if the immune system is weakened.

The bacteria are usually transmitted by touch - but can become airborne through shedding skin cells, coughing or sneezing.

How common are such infections?

About a third of healthy people carry Staphylococcus aureus bacteria

Infections linked to Cryptococcus or Mucor are relatively rare - but "Staph" infections are much more common.

Staphylococcus aureus accounts for about 110 infections every month at Scottish hospitals.

Bacteria, viruses or other micro-organisms that cause disease are collectively known as pathogens - and there are a lot of them. Other common varieties found in hospitals are:

Escherichia coli - better known as E. coli. It's a bacteria found in the intestines of humans and animals. It can be spread through contaminated food, touching animals or poor hygiene. Some strains such as E. coli O157 produce toxins that can make people very ill but most people get better without medical treatment. There are nearly 400 cases a month reported at Scottish hospitals.

Clostridioides difficile - previously known as Clostridium difficile and abbreviated to C. diff. A very common type of bacteria, particularly prevalent in the soil which can cause a bowel infection and diarrhoea. It can particularly affect people who have been treated with antibiotics or who have been in hospital for a long time. Nearly 350 cases are reported a month on average at Scottish hospitals.

What about MRSA?

It's a variant of Staphylococcus aureus that has become resistant to several widely-used antibiotics - MRSA actually stands for Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The media sometimes refers to it as a "hospital superbug" as it mainly affects people staying in hospitals.

This is because such patients often have wounds or catheters that allow it to get into their body. A weakened immune system makes it more dangerous - and the concentration of unwell people inevitable in a hospital increases the chance of it spreading.

MRSA has become a serious problem in recent years, with many experts blaming a misuse of antibiotics - overprescribing or failing to complete the full course - which has allowed these resistant strains of Staph bacteria to multiply.

Is the problem getting worse?

Some progress has been made. A decade ago about 200 Staphylococcus aureus infections were recorded a month in Scottish hospitals.

That's fallen to about 110 a month, according to the most recent figures, although most of that improvement came in the years to 2012. Since then infection rates have been stubbornly static.

A major outbreak of C. diff was a contributory factor in 34 deaths at Vale of Leven Hospital in West Dunbartonshire between 2007 and 2008. An inquiry blamed "serious personal and systemic" failures" at the hospital.

But over the decade since then, the rate of C. diff infection has steadily fallen. For E. coli, a lack of historic data makes it harder to identify a trend.

What are hospitals doing about it?

In Scotland there's a national infection control strategy including a 10-point list of standard precautions:

Assess patients as soon as they arrive and identify the risks

Hand hygiene - a detailed set of procedures

Respiratory and cough hygiene rules

Protective equipment - gloves, double gloving, aprons, eye visors etc

Equipment - single-use items, decontamination procedures

Safe environment - areas should be visibly clean, with cleaning procedures in place

Linen - safe storage and transport for cleaning, with contamination dealt with appropriately

Safe management of blood and body fluid spillages

Safe disposal of waste, including sharps

Safe work practices, training and reporting of incidents

When an infection outbreak is identified a plan for tackling it is put in place including a "deep clean" of the area.

The National Clinical Director for NHS Scotland Jason Leitch says rates of hospital-acquired infections are low but remain a "fact of life in our healthcare system".

"The fact they are rare events gives us all the more opportunity to learn from them, and aim for zero," he added.

"That would be our hope that Scotland, although leading the world in infection control, would get better still."