Who owns Scotland? The changing face of Scotland's landowners

- Published

How does land ownership affect Scotland’s people and environment?

For centuries, the Scottish countryside has been dominated by the image of tweed-clad lairds and their wealthy friends hunting, shooting and fishing on sprawling, heather-covered estates.

The entitlement and privilege that built this way of life survived almost intact for more than 500 years, with Scotland said to have the most unequal land ownership in the western world.

More recently, a new breed of owner has emerged alongside attempts by the Scottish government to modernise the rules.

But campaigners argue that the reforms have not gone far enough, and that the concentration of land in so few hands is still leading to abuses of power.

This article was inspired by questions sent in by readers of the BBC website.

So who owns what in Scotland?

Ben Nevis, Scotland's tallest mountain, was sold to the John Muir Trust in 2000

Unfortunately, this is a tough one to answer.

The basic problem is that it's not as easy as it could - and many would argue should - be to find out who owns which piece of land in Scotland.

A Scottish government project which aims to map who owns every part of the country by 2024 was launched five years ago, but has so far only managed to register about a third of the country's total land mass.

The government believes 57% of rural land is in private hands, with about 12.5% owned by public bodies, 3% under community ownership and about 2.5% is owned by charities and other third sector organisations. The remainder is thought to be owned by smaller estates and farms which are not recorded in those figures.

The Green MSP and land reform campaigner Andy Wightman reckons that half of the country's rural land is owned by only 432 landowners - a picture that has remained largely unchanged in recent decades.

This is a problem, according to a report by the Scottish Land Commission, because having so much land in so few hands can lead to abuses of power.

But the landowners are pushing back, fed up with what they describe as outdated stereotypes of their businesses.

The Duke, the Sheikh and the Danish billionaire

The Duke of Buccleuch has been selling off parts of his vast estate in recent years

The continued dominance of the private estates in rural Scotland can't be underestimated, and they often remain in the hands of the same families for generations - an average of 122 years, according to the Scottish Land Fund. Grouse shooting, deer stalking and other country sports are said to be worth £350m to the country's economy.

The most prominent of the more traditional big landowners is the Duke of Buccleuch, who has moved to slim down his holdings in recent years but still owns about 200,000 acres, much of it in the south of Scotland.

However, the Duke was recently overtaken as the country's biggest private landowner by the billionaire Danish clothing tycoon Anders Holch Povlsen, who represents a newer generation of Highland laird.

Anders Holch Povlsen made his fortune through a clothing and retail empire in his native Denmark

Mr Povlsen is said to have fallen in love with the Highlands during a childhood fishing trip, and now owns about 220,000 acres spread across 12 estates in Sutherland and the Grampian mountains.

He recently thanked the people of Scotland for their support after three of his children died in April's attacks in Sri Lanka, and said the Highlands had given his family "special memories" over the years.

The billionaire ruler of Dubai, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum, has also been busy snapping up about 63,000 acres of Scotland's countryside, and plans to build a plush new nine-bedroom lodge at Inverinate in Wester Ross.

The site already boasts a triple helipad and a 16-bed luxury hunting lodge - but the latest proposals have drawn objections from locals.

Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid al-Maktoum owns Inverinate Estate in Kyle of Lochalsh

But the biggest landowner is...

Us. Or, to be more exact, the government agencies and other public bodies who manage huge areas of land on behalf of the nation.

By far the biggest of these is Forestry and Land Scotland, which was known until very recently as Forest Enterprise Scotland. It manages more than a million acres of public forest that is said to generate about £395m for the economy every year, largely through timber and tourism.

Elsewhere, about half of the Scottish coastal foreshore is held as part of the Crown Estate, while Scottish Natural Heritage owns a string of nature reserves across the country, such as Tentsmuir in Fife.

A farmer looks out over Loch Harport on the Isle of Skye

The National Trust for Scotland owns about 180,000 acres of land alongside the 130 properties it manages, and the MoD also still owns large swathes of countryside - such as the 25,000 acres of moorland at Cape Wrath in the north west of Scotland - which is primarily used for military training exercises.

Scotland's 32 local councils own about 81,000 acres between them, while conservation charity the John Muir Trust owns 60,000 acres, including the Ben Nevis Estate, and RSPB Scotland owns 125,858 acres of land for its network of reserves across the country.

One of the more surprising names on the list of the country's biggest landowners is the Church of England - which bought up about 32,000 acres of Scottish forestry in 2014 as part of a massive expansion of its investment portfolio.

What about absentee landlords?

Historically many parts of rural Scotland, such as the Isle of Eigg, have suffered from issues with absentee landowners - people who own a piece of land but do not live on it, and who potentially do not pay as much attention to it as they might.

But despite the amount of publicity given to the likes of Mr Povlsen and Sheikh Mohammed, the number of landowners who don't actually live in Scotland is not as big as you might imagine.

Registers of Scotland (RoS) says that just 6% of the titles it has recorded (104,257) are registered with an owner who has an address outside Scotland.

The vast majority of these were to people living in other parts of the UK, while about 24,117 are registered to overseas addresses.

However, research by Mr Wightman suggests that 750,000 acres of the country is owned in overseas tax havens, while separate RoS data suggests property in Scotland worth £2.9bn is owned by offshore companies.

Owning Scottish property through offshore companies is not illegal, but it does mean the landowners duck out of paying the likes of inheritance duties and capital gains tax - which are used to fund public services such as the NHS.

How big of a problem is all of this?

In a report published earlier this year, external, the Scottish Land Commission called for a radical reform of the country's land ownership rules, and warned that having so much land in so few hands was causing "significant and long-term damage" to some rural communities.

The commission, which was set up by the Scottish government, argued that the "land monopoly" that exists in many areas gives landowners far too much power over things like land use, economic development and housing.

And it said there was an "urgent need" for measures to be put in place to protect fragile communities, including tenant farmers, from the "irresponsible exercise of power".

Sheep farmers gather at Lairg auction

It did not single anyone out for criticism, and stressed that the problems were not confined to private landlords - with public bodies also causing issues in some areas.

The commission also said owners in many areas had a positive impact on the local community and economy, and highlighted how some were actively increasing the diversity of ownership by selling off some of their land.

But Sarah-Jane Laing, chief executive of Scottish Land and Estates (SLE) - which represents landowners - is worried that the land commission "still sees land ownership rather than land use as the prime route to dealing with issues being faced by communities".

Ms Laing says several SLE members, including Dalkeith Country Park near Edinburgh, have diversified into areas such as tourism and renewable energy.

The SLE also points out that Scotland's three new towns, such as Tornagrain in the Highlands, are being developed by rural landowners, and that private estates support about 8,000 jobs nationwide.

What is being done about it?

There have been some fairly big changes to land laws in recent years, largely aimed at making it easier for local communities to purchase the land they live on.

Among the most high-profile of these community buyouts have been on the Isle of Eigg and on the South Uist Estate, which includes the islands of Benbecula and Eriskay.

Islanders completed their purchase of Eigg in 1997

The latter of these saw 3,500 islanders join forces to raise the £4.5m it took to buy the estate's 93,000 acres and 850 crofts from absentee landlords in 2006.

Since then, residents have built three huge wind turbines - named Wendy, Fanny and Blowy - which have helped to boost the economy of the islands.

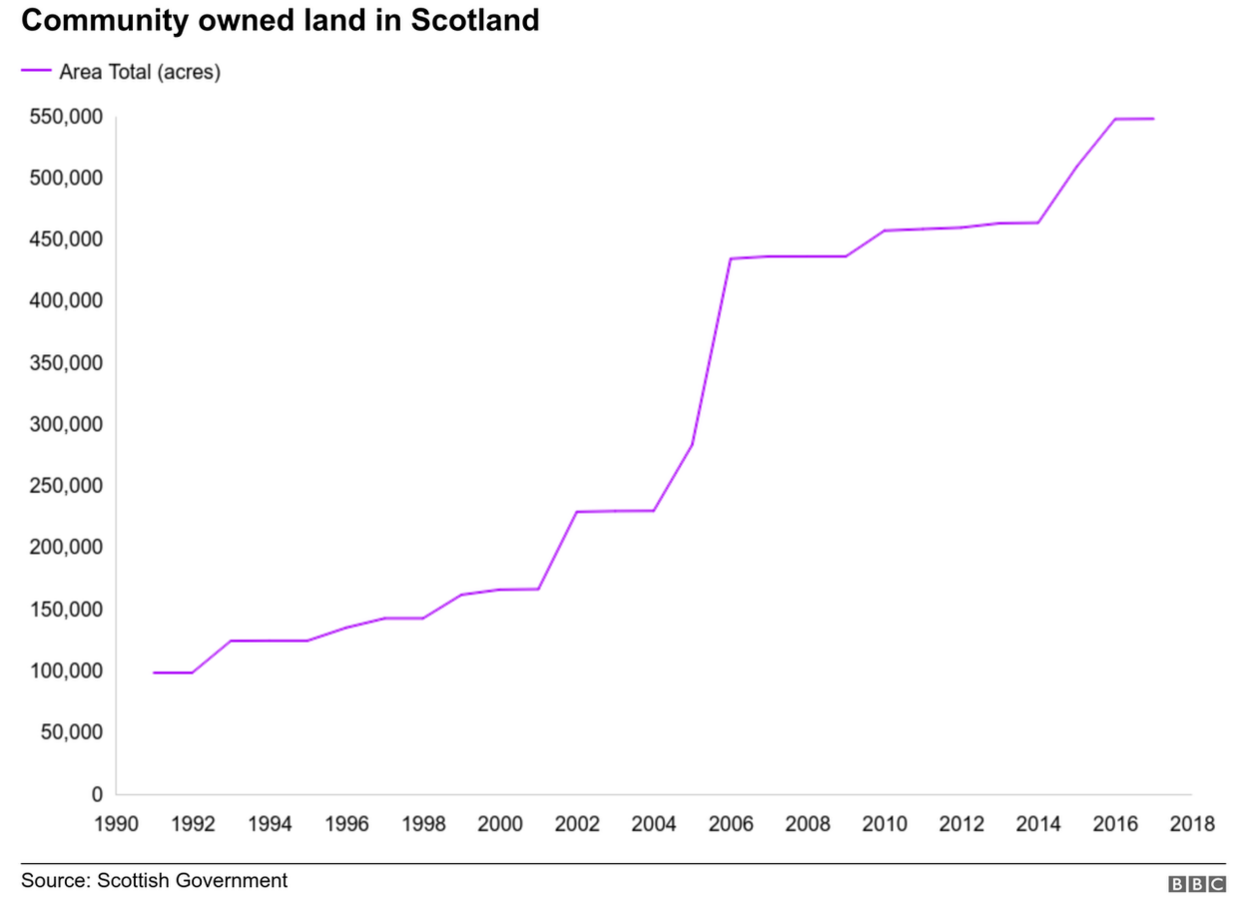

Alex Salmond, the then-first minister, set a target in 2013 of one million acres of Scotland being owned by local communities by the end of 2020.

The latest available figures show there are now 562,230 acres in community ownership across the country - including a Cold War surveillance station on the Isle of Lewis and a former church in Edinburgh.

Ministers are also considering the recommendations of the Scottish Land Commission, which include a public interest test for significant land transfers.

Further reforms seem highly likely, with government ministers consistently stressing that land reform is on a "radical journey".

Ian Cooke, director of Development Trusts Association Scotland, which helps community groups secure land, said: "For a range of reasons, I don't think many people thought this was a realistic target when Alex Salmond announced it, but it has usefully focused minds and driven activity towards more community ownership."

Mr Cooke points out "community ownership is a means to an end, rather than an end itself" and predicted a bigger role for local people in the lands around them in the future.

Do you have any other questions around land ownership - or any other topic - in Scotland that you'd like us to investigate?

Use the tool below and we could be in touch.

If you are reading this page on the BBC News app, you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question on this topic.