Subsea alarm warns of North Sea oil well leaks

- Published

A total of 2,379 North Sea wells are expected to be decommissioned in the next 10 years

A team of Scotland-based researchers has developed a new technique to protect the environment if a decommissioned oil well springs a leak.

The new system's secret ingredient is a special substance that "pretends" to be oil - and then calls a satellite.

When the first North Sea oil came ashore in 1975, the future looked bright. These days we are a lot closer to the end of the rainbow.

Some North Sea oil and gas fields are already played out.

That doesn't just mean removing structures on and above the surface. Beneath the waves, wells must be capped securely to prevent what remains leaking out.

Kill fluid

The most up-to-date figures from the trade body Oil and Gas UK show there are around 11,000 wells in the North Sea.

A total of 2,379 of them are expected to be decommissioned in the next 10 years.

There are established techniques for stopping the flow and capping them, but who - or what - will raise the alarm if one starts to leak?

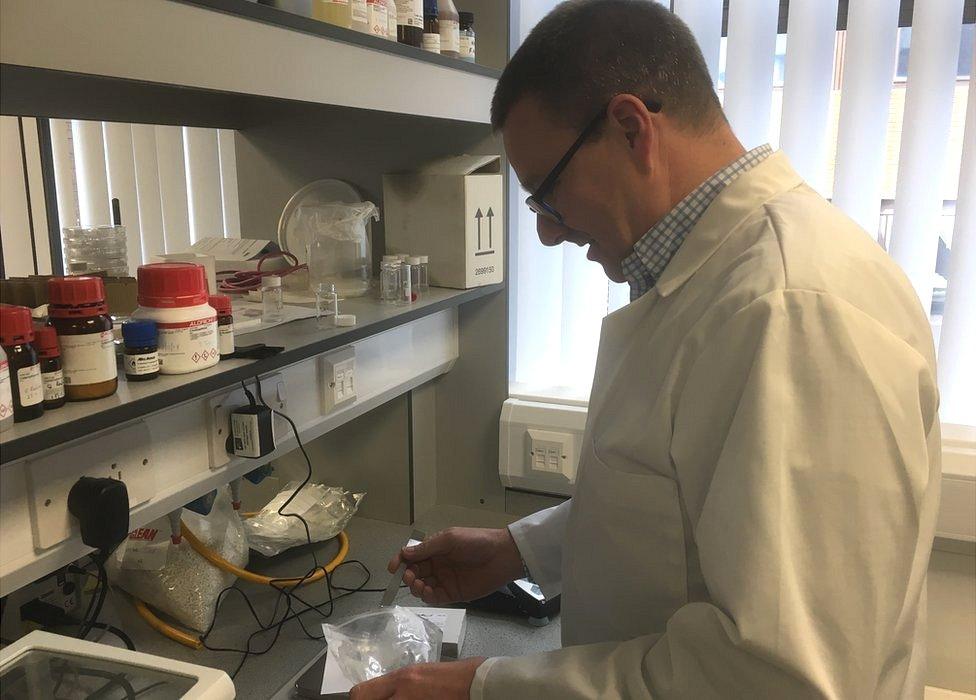

Professor David Bucknall, who holds the chair of materials chemistry at Heriot-Watt university in Edinburgh, leads a team that has developed a vital ingredient for something designed to act like a domestic smoke alarm.

Except this alarm will sit on the seabed at a capped well, and the ingredient is a fluid called SWIFT.

"It's a compound that we add to what they call the kill fluid," he says, "which is fluid they add to fill up the holes.

"They're then capped with concrete and the idea is that they should remain sealed forever.

"But if there ever is a crack or a failure in the pipe, then our fluid will come out."

Above it, a detector is waiting to be triggered by the fluid.

Professor David Bucknall says the system is designed to act like a domestic smoke alarm

"At that point the detector releases a buoy," the professor says, "and the buoy pings up to the satellite network and tells the controllers not only where it is but which well they have to go and look at and fix."

The concept of leaking fluid triggering a satellite buoy came from the Aberdeen-based company Sentinel Subsea.

They wanted a tracer compound that could withstand being held in a capped well for 100 years but would not harm the environment.

Secret formula

Heriot-Watt was approached to develop the compound. Its formula remains a trade secret.

Professor Bucknall says his team were able to simulate a century beneath the waves in a matter of months in the laboratory. "Depending on the depth, it has quite a large temperature gradient to survive in.

"The company also wants it to sit there for up to 100 years without reacting, so it has to be very passive in its behaviour.

"But it also has to act in a way that would simulate things in the oil well.

"So it has to pretend to be oil, but be sufficiently different enough from oil so we can distinguish it is coming from that well and not from some other source."

The aim of Sentinel Subsea has been to develop a system which both protects the environment and keeps oil companies' costs down.

The partnership with Heriot-Watt was supported by the Oil and Gas Innovation Centre (OGIC), which acts as a matchmaker between Scotland's universities and businesses in the sector.

OGIC's chief executive Ian Philips says 2017 was the first year in which the number of North Sea wells being decommissioned was higher than the number of new wells being drilled.

"With the total decommissioning expenditure over the next 10 years expected to reach £15.3bn on the UK continental shelf alone," he says, "collaborations like this... have the potential to bring further cost efficiencies and increase environmental safety standards."

The next steps will involve more laboratory and simulated field trials before independent validation tests take place.

The system is likely to be fitted to real capped wells later in 2019.

North Sea oil has provided an economic lifeline for almost half a century.

But nothing lasts forever, and this system holds out the prospect that it won't outstay its welcome.