The RAF weathermen who helped save D-Day

- Published

The 518 squadron flew missions from Tiree almost every day no matter what the weather

D-Day could have been one of the biggest disasters in military history were it not for the decisions of a Scottish weatherman and data from an RAF squadron based on a small island off Scotland's west coast.

Group Captain James Martin Stagg, from Dalkeith near Edinburgh, was the chief meteorological adviser who persuaded US General Eisenhower to change the date of the Allied invasion.

Stagg not only predicted a storm on 5 June 1944, but made the vital forecast that the weather would break for long enough the following day to allow Operation Overlord to go ahead.

Some of the data that helped inform Stagg's decision came from a little-known RAF squadron operating on Tiree.

The 518 Squadron flew dangerous missions from Scotland's west coast hundreds of miles out into the Atlantic in all weathers to send back meteorological readings.

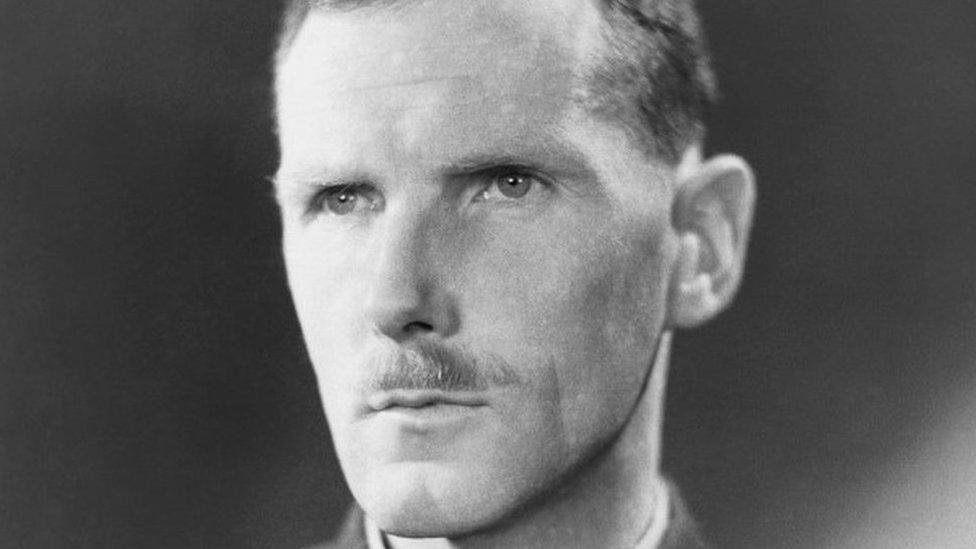

Group Captain Stagg was the chief meteorological adviser to Operation Overlord

The Normandy landings were the largest seaborne invasion in history and laid the foundations for the Allied victory in World War Two.

They had been planned for 5 June but low tides and good weather were vital to be able to get hundreds of thousands of troops on to the beaches of France.

The low tides were easy to predict but getting the weather right as well was another matter.

Low cloud would mean no air cover and rough seas could sink landing craft.

U.S Troops rushing to the Normandy Beaches in France during the D-Day landing

In those days, many years before satellite imaging and computer modelling, weather forecasting was far from an exact science.

Prof Liz Bentley, from the Royal Meteorological Society, said: "In 1944, the forecaster was reliant on pure weather observations."

However, observations from land stations could not tell forecasters what the weather was like far out in the Atlantic.

This was where the 518 squadron came in.

Some of the crew from 518 squadron on the beach at Tiree

It was their job to fly from the inner Hebrides out over the Atlantic in specially-equipped bombers and record the weather conditions.

Dr John Holliday, a local historian on Tiree, said the story of the 518 squadron's contribution has never properly been told.

The Normandy landings were the largest seaborne invasion in history

The RAF unit moved to the island in September 1943 from Stornoway on Lewis.

According to Dr Holliday, their mission was to fly on two "tracks" for hundreds of miles over the Atlantic and radio back temperature and air pressure measurements, which were fed to the headquarters near London.

The squadron used Halifax bombers, which had all their bombing equipment stripped out to help them fly the long-range sorties.

Dr Holliday says the missions could take eight to 10 hours and were often conducted at night and in severe weather conditions, requiring "amazing" navigation skills.

The graves of some of the men that died are in this Tiree cemetery

"Consequently they lost a lot of men," he says.

"This was one of the most dangerous stations to be in."

In January 1944, eight men died when a meteorological flight got lost in bad weather and hit cliffs at Bundoran in Donegal.

Dr Holliday says: "I'm struck with admiration when you look at what they had to do and read their descriptions of the battering they got out in the Atlantic. It is just extraordinary."

An aerial view of Allied Naval forces engaged in Operation Overlord on 6 June 1944

The island of Tiree was transformed by the presence of about 3,000 military personnel, with many from Canada, New Zealand, Australia and Poland as well as the UK.

One of the squadron crew, Warrant Officer Gordon Wilkes, later wrote: "We were never glamorised on the front page of the daily newspapers, or talked about in pubs and bars, but we were always there, whatever the weather."

He calculated that 10 aircraft and 54 crew were lost while operating from Tiree in 1944.

Meanwhile, in the south of England, at the heart of the Allied Supreme command, was Group Captain Stagg.

Using the data from Tiree and other squadrons, he fought to convince General Eisenhower to delay the landings by one day.

General Dwight Eisenhower was the commander of Allied forces in Europe

Eventually Eisenhower listened and the largest maritime operation in history was put on hold.

Prof Bentley, from the Royal Meteorological Society, said there was much disagreement between the US and UK forecasters.

She says: "They had ruled out 5 June as too stormy but Stagg had seen one observation about 600 miles to the west of Ireland that showed the surface pressure was beginning to rise, so there was potential for things to settle down."

They came back on the morning of 5 June to check if this was still the case.

A break in the weather allowed the invasion to go ahead

Stagg felt there was an opportunity for a small ridge of high pressure to be settling in the English Channel the next morning but he was still met with disagreement.

Prof Bentley said it was likely that the German forecasters were also expecting the bad weather to continue and had not expected an invasion under those conditions.

If the D-Day landing had not taken place on 6 June they would have been delayed for two weeks and on that day the Channel was again hit by a large storm, which meteorologists would have struggled to forecast.

Instead, Stagg was proved right and the D-Day invasion went ahead on 6 June, beginning the liberation of German-occupied France, and later Europe, from Nazi control.