Scapa Flow scuttling: The day the German navy sank its own ships

- Published

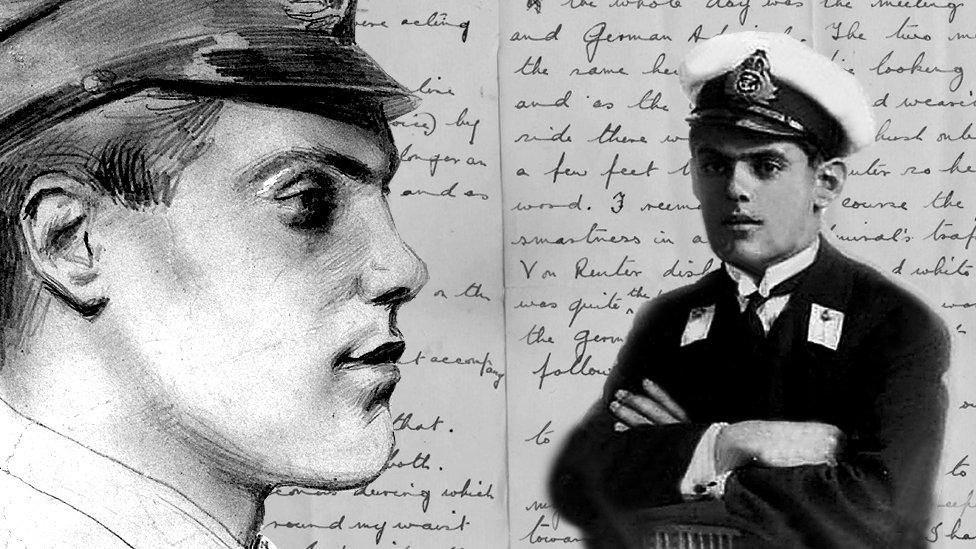

German battleships sinking off the island of Fara

In waters off Orkney a century ago, 52 German warships were sunk in one day - but this huge naval loss was not inflicted by enemy forces.

Instead the scuttling of the German High Seas Fleet in Scapa Flow was a deliberate act of sabotage ordered by a commander who refused to let his ships become the spoils of war.

It was the single greatest loss of warships in history and the nine German sailors killed that day were the last to die during World War One. The final peace treaty was signed just a week later.

After the fighting in WW1 ended in November 1918, the entire German fleet was ordered to gather together in the Firth of Forth, near Edinburgh, to be "interned" by Allied forces.

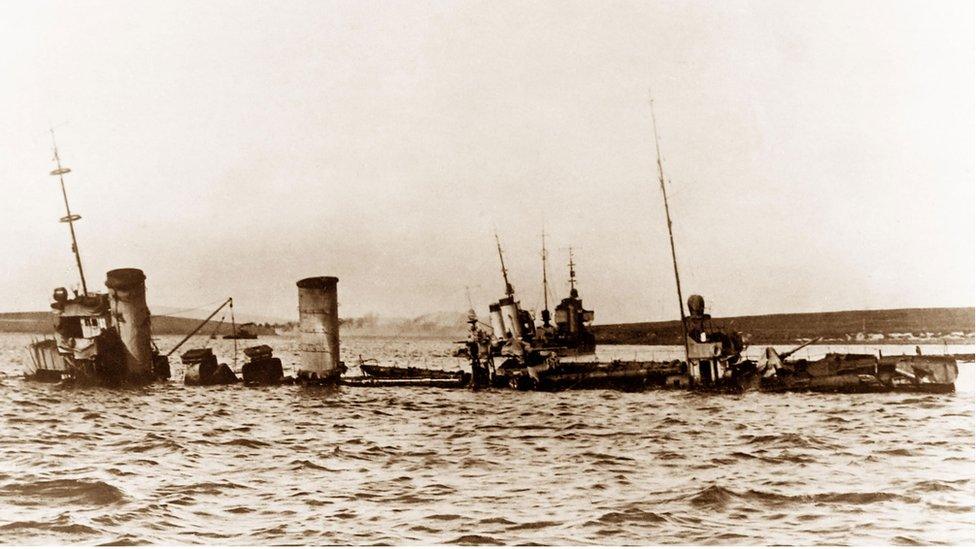

The battlecruiser Derflinger just four minutes before it disappeared beneath the surface

Nine German battleships, five battlecruisers, seven light cruisers and 49 destroyers - the most modern ships of the German High Seas Fleet - were handed over to the victorious forces off the east of Scotland.

Within a week, the 70 German ships were escorted to the sheltered waters of Scapa Flow, off Orkney, where they and four other vessels were held while the details of the peace talks were worked out.

The final decision on their fate was to be taken at Versailles, but until then German sailors were kept on board their ships in the vast natural harbour. At Versailles, the victorious powers wrangled over what to do with the ships. Britain and the US wanted them destroyed. The French and Italians thought it better to share them out between the Allies.

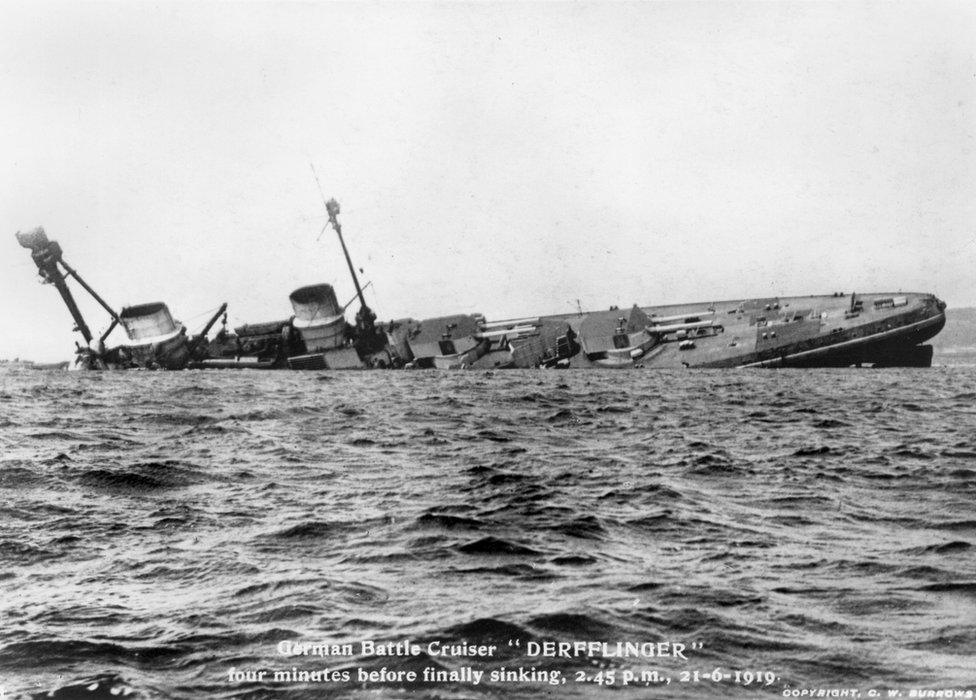

The fleet was in Scapa Flow for seven months before it was scuttled

"The ships were not actually surrendered and that's why there were no British troops on board them to prevent them being scuttled," Tom Muir from Orkney Museum told BBC Radio Scotland's When the Fleet Went Down. "They were German government property and remained that throughout their time here."

The German commander, Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, was not kept informed of what was happening outside of his ships. He had to rely on briefings from British commanders and old copies of the Times newspaper, according to Tom Muir.

The peace talks had been intended to conclude on 21 June but the deadline was extended. As far as von Reuter knew the talks had failed and he was fully expecting his ships to be boarded and seized by the Royal Navy. The German admiral felt duty-bound not to let that happen.

Mr Muir says: "Von Reuter had already sent letters around the commanders of the ships telling them that he was planning to have the fleet scuttled at his signal. Ironically it was the British drifters who were carting those letters around to the officers on the other ships."

On the morning of 21 June 1919, the British fleet took advantage of good weather to steam out of the harbour on exercise. At 10:30, von Reuter's flagship, Emden, sent out the seemingly innocuous message - "Paragraph Eleven; confirm". It was a code ordering his men to scuttle their own ships.

The day the German High Seas Fleet sank

52Warships sank to the seabed

9German sailors were killed

7months after the end of World War One

7wrecks still lie in Scapa Flow today

The "paragraph eleven" signal, using semaphore and searchlights, took a while to reach all the ships because they were positioned right across the vast flow. "They would have waited and like a wave it went through the ships from north to south," says Mr Muir.

Beneath decks, German sailors began to open seacocks - valves that allow water in - and smash pipes. Mr Muir says: "They had all been deliberately flooded from one side first so that they would turn over and sink because they believed it would make it more difficult for them to salvage them."

At first it was not clear what was happening and it took a couple of hours before it became apparent that the Germans had deliberately sunk their ships.

The German sailors took to small boats to escape their sinking ships as the few remaining British sailors onboard Royal Navy drifters, small vessels about the size of fishing trawlers which often escorted destroyers, tried to work out what to do.

The crew of a German destroyer abandoning ship

The only civilian witnesses were schoolchildren from Stromness who were on a trip to view the German fleet onboard a water tender.

One of the schoolchildren, 12-year-old Leslie Thorpe, wrote that one German boat full of fleeing soldiers did not have a white flag and the British fired on it with a machine gun.

"The one thing that should not be forgotten is men died that day," says Mr Muir. "We see all these images and it is just a huge piece of metal rolling over in the sea and sinking and you forget about the cost in human terms.

"The men in the drifters were ordered to open fire on the defenceless German sailors. They had no weapons, they were not allowed them and they didn't have any."

It is believed nine Germans died as a result of the actions that day.

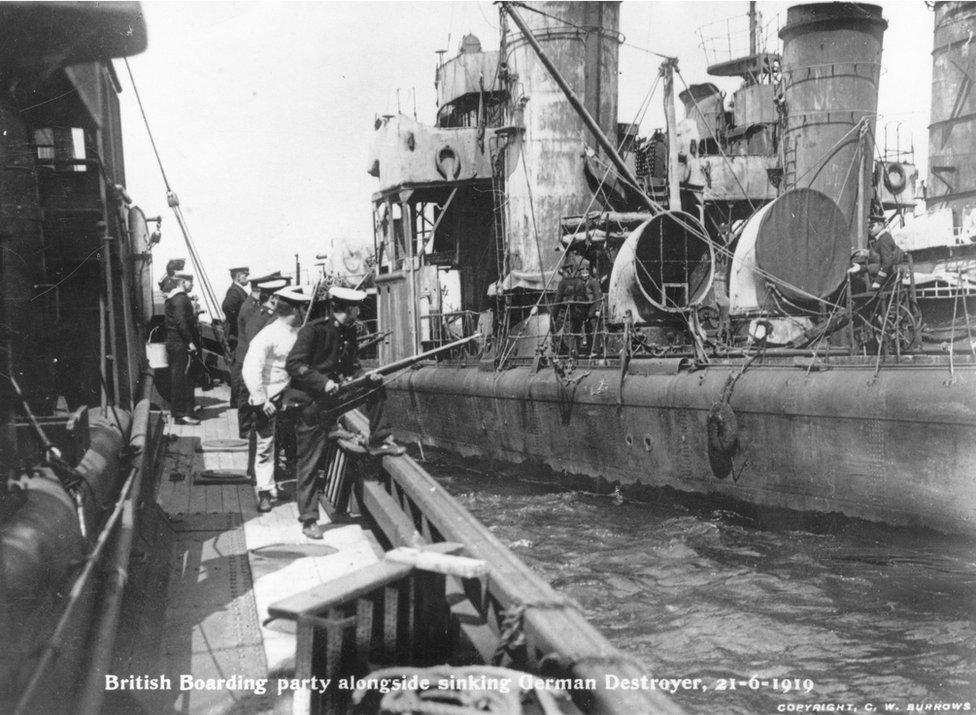

British Boarding Party alongside a German destroyer

By 17:00, most of the German High Seas Fleet had disappeared beneath the surface of Scapa Flow. The Hindenburg, the biggest German battlecruiser, was the last to sink.

During the 1920s and '30s many of the 52 ships were lifted from the sea bed by commercial contractors and broken up.

The seven wrecks that remain are now classed as scheduled monuments, nationally important archaeological sites given protection against unauthorised change. Earlier this week it emerged that four of the vessels, which are now owned by a retired diving contractor, are being sold on eBay.

"The scuttling of the German fleet removed them from being a bargaining chip in peace negotiations but it was seen as a hostile act by the British," says Mr Muir. "In Germany it was seen as a way of restoring some honour. The navy had not let the ships fall into enemy hands."

A senior German officer declared at the time that this act had wiped away the "stain of surrender" from the German fleet.

When the Fleet Went Down: Scapa Flow @100 is on BBC Radio Scotland at 11:30 on Friday 21 June

- Published21 November 2018

- Published19 June 2015