Q&A: Could social care charges in Scotland be abolished?

- Published

The SNP has pledged to scrap non-residential social care charges

SNP leader and Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has made a pledge that if her party is re-elected in 2021 it would scrap all non-residential social care charges. But what things do people currently get for free and what has to be paid for?

The background to free care in Scotland

Free personal care won the unanimous backing of Holyrood, external more than 17 years ago. The "flagship policy" enacted by a Scottish Parliament of just three years old meant people over the age of 65 were entitled to free services in their own home like help with getting in and out of bed, showering, bathing and eating.

At this year's SNP conference in Aberdeen, Ms Sturgeon reiterated that commitment set in 2002. She told party members that the "the principle behind free personal care is the same as free health care - if you need help you should get it".

The policy was enhanced in April when - under a move known as Frank's Law - free personal care was extended to people under the age of 65 who live with disabilities and degenerative conditions.

The legal change was brought in memory of the late Dundee United footballer Frank Kopel.

He was diagnosed with dementia at 59, but was too young to qualify for free care. So his wife Amanda campaigned over many years to have the law looked at again. Frank died in April 2014 and never benefited from the change.

So what do people have to pay for now?

While NHS care and personal care is free, fees are charged for a raft of services provided by local authorities in people's own homes.

Councils have the power to charge for things like;

meals on wheels

wardens, sheltered housing

making beds

community alarms

and laundry.

Income from these types of care service is estimated to be in excess of £30m a year.

How much are people charged?

What councils charge per serving

£3.45Edinburgh

£3.33Glasgow

£3.10Dundee

£2.56Renfrewshire

The fees vary across the country. Local authorities in Scotland set their own rules on charging and have their own charging policies. They can use their discretion about which services are charged for and the amount.

For example, in Edinburgh meals at home are charged at £3.45 a community alarm is £4 per week and transport is £2 per journey.

In Glasgow, the council charges £3.33 for every meal at home, alarms cost £3.37 a week, and home care services are £17.67 an hour.

In Dundee the charges look like the following: delivered food £3.10 per meal, community alarm £2.85 per week, handyperson services £3.90 per 15 minutes.

What's changing and why announce it now?

Nicola Sturgeon said her government would abolish these fees for social care provided at home if she were re-elected first minister.

It is unlikely the move would come into force immediately. Frank's Law, which was formally announced in September 2017 only came into effect in April this year.

But making the pledge public now gives a two-year lead-in time and offers local authorities a chance to plan for the changes.

Scotland's ageing population means people are living longer but with more complex needs.

The Scottish government wants more people to stay at home for as long as possible and avoid lengthy or unnecessary hospital stays or nursing home stays.

Nicola Sturgeon said: "I know from my own constituency experience that charges can be a barrier to people accessing the support they need.

"And if they can't get that support in their own homes, they are more likely to end up in hospital."

But there is huge uncertainty associated with projecting the future costs of long-term care and that probably means re-modelling regularly how it is delivered.

Is it affordable and will it happen?

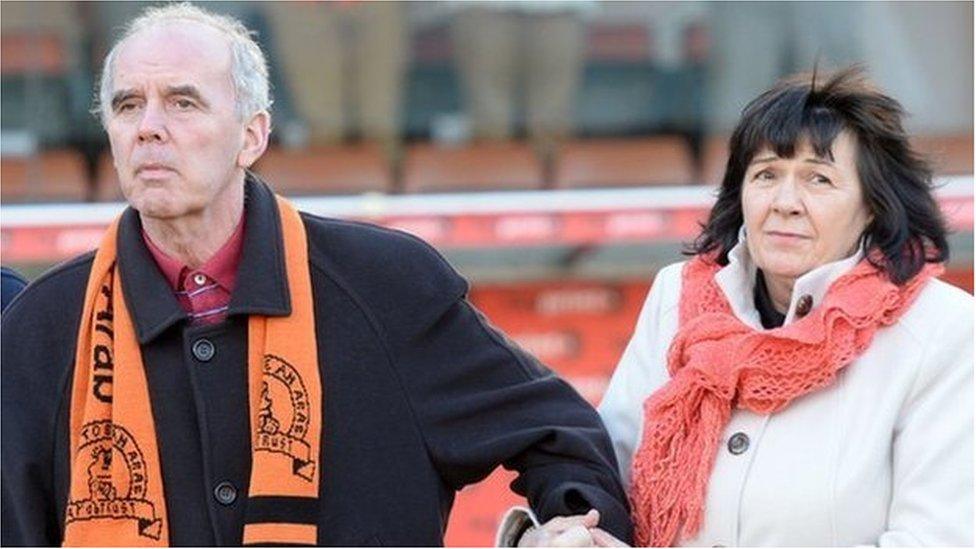

Amanda Kopel has campaigned for a change in the law since before her husband Frank died

At this stage this is a simple policy pledge and there is not much detail. Local authorities will have to provide the service and they are likely to put pressure on the Scottish government to help fund it.

Cosla, the umbrella body that speaks for Scotland's councils said it would look closely at "any plans put forward by a future administration which have a direct effect on local government and the social care support our communities receive".

A spokesman added: "We will continue to work with the Scottish government on implementing health and social care integration and reform in adult social care and, if necessary, will work with Scottish government to scope out this specific pledge.

"It is important to consider this proposal in the wider context of Cosla's ask for a fair deal in this year's local government settlement."

Big Scotland-wide policies, such as care for the disabled elderly, bring with them issues on implementation.

Take the latest move to fund personal care for under 65s. Mrs Kopel said she was continuing to hear of cases where people are being denied free personal care, despite the new law.