'Just transition': How will oil towns survive move to greener world?

- Published

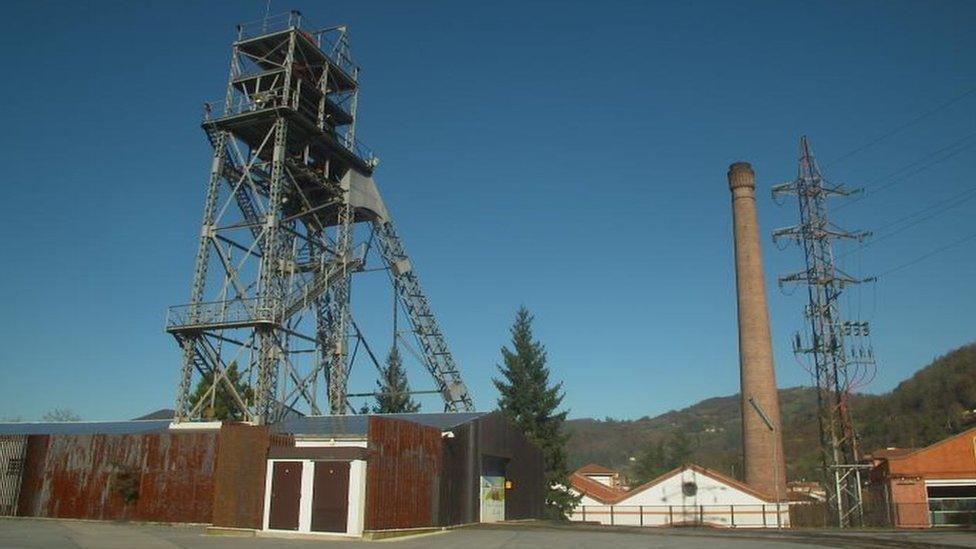

Much of Asturias, in the north of Spain, is dominated by the remains of old industries

How can places like Aberdeen - where the economy is built on oil - be shielded from economic damage when the climate crisis forces a transition away from fossil fuels?

Well, over the next 18 months, a Scottish government-appointed commission will grapple with that very question.

The aim is to avoid the impact felt in places like Fife after the coal mines closed in the 1980s.

The concept of "just transition" is being considered by many nations meeting this week at the UN Climate Change conference in Madrid.

Appropriately, the host nation for COP25 is leading the way in justice for communities being hit by the need to reduce our emissions.

A 250m euro fund was announced last year by the Spanish government to help people whose pits are being shut.

Much of that is happening in Asturias in the north of Spain where hundreds of mines closed in the 1990s with devastating consequences.

Retired miner Artemio Fernandez Alvarez said: "It was a total impact because they hadn't thought about any other alternative. It was a total closure of mining. The valley used to have up to 24,000 and it went down to not even 4,000."

For many former miners their only connection to the industry now is through a traditional choir

Fellow miner Salvador Fernandez Tunon added: "If there had been a change it should have come with new jobs. They created a few companies but they only lasted two years. And we don't know where that money went."

That was in the past for those who once dug the rich coal seams at Mieres in the Turon Valley.

With the industry long gone, their link now is through the miners' choir which performs across the country in trademark boiler suits, helmet lamps and steel toe-capped boots.

Generally, they are living comfortably enough but they fear for younger generations.

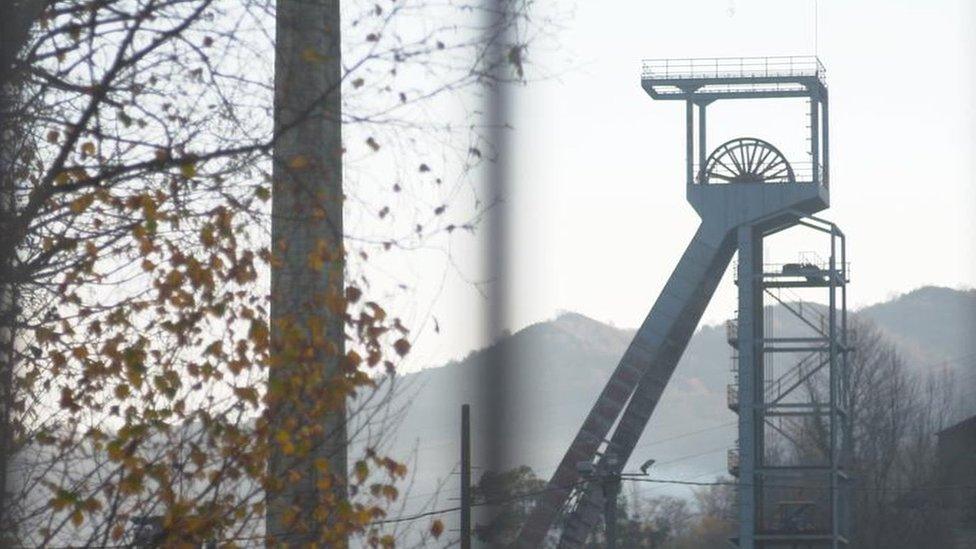

Former mine workings are being used to harness geothermal energy

Mario Coto Coto said: "Young people don't have access to anything. The majority have to leave. Maybe a few work in retail but the job situation here is bad."

This issue is being thought about carefully back in Scotland.

A Just Transition commission was formed in 2018 and has been given two years to produce recommendations.

But Spain is ahead of the game having already committed money to the process.

One technology which has created jobs in the former mining town of Ariondo is geothermal energy.

They have flooded a mine where the ambient underground temperature warms the water which is processed through heat exchangers to create a district heating system.

Gregorio Rabanal Martinez, president of HUNOSA Group, said it provides alternative employment to some of those who lost their jobs when the mines closed.

But added: "That company had 23,000 workers in the 80s. Now we have 1,000 workers but still are the biggest company in that area.

Pit heads remain as a reminder of the industry which once dominated the region

Just next door, the University of Oviedo is researching alternative energy sources to coal.

Dr Eduardo Alvarez Alvarez explained: "It's a problem but it's also an opportunity because we now have some industrial companies which don't really demand a lot of energy.

"So, if we are able to attract new investors and prepare new sources of energy then we will be able to give them energy at a low price."

On a global scale, the energy transition in Scotland is much less urgent than that in Spain.

Coal is the dirtiest, most polluting hydrocarbon and to meet our climate change ambitions it has to be replaced quickly.

But First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has already said her government's support for oil and gas will now be conditional on a "just transition".

And so a lot of attention is being paid to what is happening in Spain.

- Published2 December 2019

- Published26 November 2019

- Published13 November 2019