Climate change: The COP25 talks trying to change the world

- Published

We know the warnings by now.

2019 is on course to be in the top three warmest years on record.

The UK government has declared a national climate emergency.

And now, UN Secretary General António Guterres says the "point of no return is no longer over the horizon".

That came ahead of the UN's two-week gathering of countries to discuss climate change and set targets - the 25th Conference of the Parties (COP25).

So what really gets done at these conferences - and do they actually work?

Climate activist Greta Thunberg was at last year's COP event in Poland

Many countries have individual targets related to climate change.

For example, the UK government has committed to cutting greenhouse gas emissions right down to net-zero by 2050.

But there are also worldwide targets for countries which take part in the UN climate change summits.

The Montreal Protocol, adopted in 1987, was an international agreement to try to heal the ozone layer, which protects Earth from ultraviolet rays but was being destroyed by man-made chemicals.

By last year it was found to be successfully healing - the Northern Hemisphere could be fully fixed by the 2030s and Antarctica by the 2060s, according to a UN report., external

The COP meetings - which focus on greenhouse gases - started in 1995. But it was 1997 when the first significant targets were set.

The Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol is named after the Japanese city where it was agreed

The Kyoto Protocol, agreed in Japan in 1997, set targets for 37 countries to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

The targets were different for each country, depending on how developed they were.

But the US pulled out in 2001 - because they were unhappy that developed countries had legally binding targets, while less developed nations didn't have binding targets.

Canada pulled out in 2011 and a lot of other countries missed their targets.

Doha in Qatar was where the Kyoto Protocol was amended

In 2012, the Kyoto Protocol was updated in Doha, Qatar.

But the deal only covered Europe and Australia, whose share of world greenhouse gas emissions was less than 15%.

However, it paved the way for the Paris Agreement in 2015 - also known as COP21 - which was another significant step in climate change talks.

The Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement went further than any other international climate change deal.

It was agreed by 195 countries in 2015 and came into force in November 2016.

Some of the main pledges were:

To keep global temperatures "well below" 2C above pre-industrial times and "endeavour to limit" them even more, to 1.5C.

To limit the amount of greenhouse gases emitted by human activity to the same levels that trees, soil and oceans can absorb naturally, beginning at some point between 2050 and 2100.

To review each country's contribution to cutting emissions every five years so they scale up to the challenge.

For rich countries to help poorer nations by providing "climate finance" to adapt to climate change and switch to renewable energy.

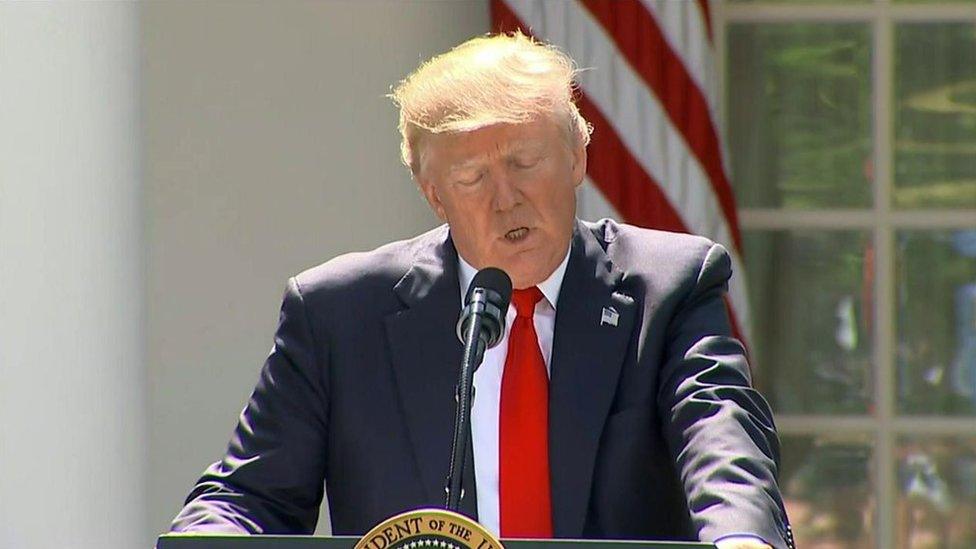

President Trump says the Paris climate accord "disadvantages" US

One of the main differences to the Paris deal was that it allowed countries to submit their own targets - rather than tell countries what their targets were.

This got the US and Canada back on board.

But since then, the US has started to withdraw from the agreement, as President Trump says it's unfair on the US economy.

He has said he wants to make it easier for fossil fuel producers in the US.

But there's an election in the US in November 2020, and a different president could cancel the withdrawal.

Do the talks actually work?

COP25 has started in Madrid and runs until 13 December

Although the Paris Agreement was generally well-received, the UN itself has said it doesn't go far enough.

A report from the UN Environment Programme in 2017 says the Paris Agreement only covers a third of the emission reductions needed.

It says that the world is still on course to warm by more than 2C.

The report recommends putting more ambitious targets in place in 2020.

COP25: What you need to know about the climate conference

Next year's targets are what's expected to be discussed at this year's COP25 in Madrid.

The 2020 summit will be held in Glasgow and countries have committed to submit new and updated national climate action plans.

The UN Secretary General António Guterres will tell the meeting that the world is now facing a full-blown climate emergency.

He said before the conference: "In the crucial 12 months ahead, it is essential that we secure more ambitious national commitments - particularly from the main emitters - to immediately start reducing greenhouse gas emissions at a pace consistent to reaching carbon neutrality by 2050."

It could be seen as an acknowledgement that while the climate change summits can be a step towards a better future, more needs to be done - and time is running out.

Follow Newsbeat on Instagram, external, Facebook, external, Twitter, external and YouTube, external.

Listen to Newsbeat live at 12:45 and 17:45 weekdays - or listen back here.

- Published2 December 2019

- Published26 November 2019

- Published3 May 2019

- Published2 December 2019

- Published12 June 2019

- Published1 June 2017

- Published5 November 2019