Sturgeon pledges radical overhaul of children in care system

- Published

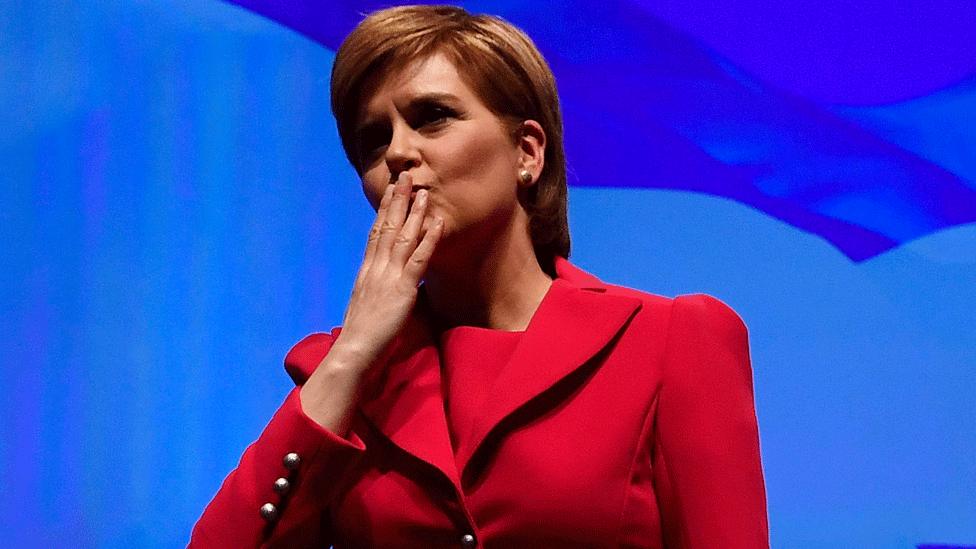

Nicola Sturgeon and John Swinney attended the launch of the review

Nicola Sturgeon has called a review into Scotland's care system "one of the most important moments" in her time as first minister.

She said she was "committed" to turning its vision for caring for young people into reality as quickly as possible.

The Independent Care Review, external said the care system should have love and nurture at its heart.

But instead, it said many young people experienced a "fractured, bureaucratic and unfeeling" system.

It said Scotland's care system was failing to give too many children the foundation they need for later life.

The independent root-and-branch review, which was instigated by Ms Sturgeon at the SNP conference in 2016, spoke to 5,500 people - more than half of whom had been in care themselves.

Ms Sturgeon praised the report for listening to the voices of those who had experienced care.

She told MSPs too many vulnerable young people had been let down and would pay the price for the rest of their lives.

The first minister said a radical overhaul was needed and a team would be set up immediately to form a plan to deliver the changes proposed in the review.

She also announced an Oversight Body which would be run by people outside the Scottish government and would include people with experience of the care system.

The review was launched at an event in Edinburgh

There are about 15,000 children in Scotland's care system.

Fiona Duncan, the chairwoman of the review, said the human cost of their distressing and disturbing experiences often had a lifelong effect.

She said the review had calculated that an "eye-watering" £875m a year was spent picking up the pieces of earlier failures in the care system.

This is money spent on mental health, homelessness and addiction services, which a far higher proportion of care leavers require as adults.

Ms Duncan questioned whether the care system was actually a "system" at all and said it could often prolong the pain it was trying to protect.

She added that people who were trying to do their best for young people were being "thwarted" by a system that operated when families and children were in crisis.

The review's findings include:

Brothers and sisters have been regularly separated and have no say about their future contact

Girls who have been sexually abused have been held in secure care

Some Children's Hearing panels struggle to understand and empathise with the young people before them

Care has become "monetised" with competition rather than collaboration

Children who have gone through secure care feel that restraint was used as punishment

Some children "actively sought restraint as it was the only time they felt human touch"

Some children feel staff were cold and stigmatising

There is an overworked and stressed workforce

Ms Duncan said the scale of the "listening" that had been done for the review demonstrated the "human cost is lifelong".

"Overcoming trauma requires a foundation of stable, nurturing, loving relationships", she said.

"However, the current 'care system' is failing to provide that foundation for far too many children."

'I was at risk of being harmed again'

Julian was taken into care as a child

Julian remembers being taken away from his parents in the middle of the night when he was five. He says it was dark, he was scared and he was not allowed to say goodbye. No-one explained where he was going or why, he says.

Even after he was taken into foster care full-time, he was not kept safe from harm, Julian says.

"I was put back into a situation where I was at risk of being harmed again," he says. "I was put into care because of neglect and the State should have been there to protect me. In many ways it failed to do that."

At the age of seven, he was adopted but he feels that neither he nor his adoptive parents were given the support they needed. He struggled at school and started self-harming.

"I was so angry and frustrated and confused and I did not know how to cope," Julian says.

At 16, he left home, moved into a homeless hostel and became addicted to alcohol. He describes the care system as a "cattle market" for homelessness.

Julian, who is now 27, says he was angry and frustrated

Julian, who is now 27, says he woke up one day and realised he needed to change.

He asked for help after years of refusing it and his early twenties went teetotal.

After studying for Highers, and an HNC, this September he is due to start a university degree studying law.

His motivation? He says his life has been dominated by legal processes over which he had no control. He believes that working within those legal processes he could help bring about change.

'Volunteer panel members'

Fiona Duncan chaired the review

Among her findings, Ms Duncan questioned whether the Children's Hearings System - where decisions are made that affect people for the rest of their lives - was fit for purpose and if it should rely on volunteers.

Children's Panels across Scotland are staffed by about 2,500 trained volunteers.

The review also called for an end to the inappropriate use of secure care and a complete overhaul of the care inspectorate.

Its recommendations include:

Everyone involved in The Children's Hearing System must be properly trained in the impact of trauma, childhood development, neuro-diversity and children's rights.

There should be changes to how panels work and who sits on them

A complete overhaul of the Care Inspectorate

No longer sending 16 and 17-year-olds to prison or detention

No longer excluding care-experienced children from school

An end to acute and crisis services

Support for families rather than stigmatisation

Ms Duncan said families were not getting the support they needed in order to keep their children at home with them.

She said if children did need to be removed from families then it was "essential" siblings were kept together for as long as it was safe to do so.

She said the whole workforce, paid and unpaid, must be supported to "love, nurture and cherish children".

For the first time the review also put a price on the annual cost of the looking after children in the care system, which is £932m.

"What we have sought to do is understand where all of the pockets of money are all across Scotland that are spent on children and young people in this thing that we call the care system," Ms Duncan said.

"It is an estimate because it was almost impossible to get access to all the information we needed. It is pretty accurate but it is a low estimate."

- Published25 July 2019

- Published19 December 2018

- Published15 October 2016