The research centre dedicated to the science of cracks

- Published

Cracks are everywhere from pavements to bridges

Whatever their size, cracks can be bad news. They make planes fall out the sky and bridges fall down. On a more mundane level they trip you up on a badly-maintained pavement.

Now Strathclyde University in Glasgow is claiming a world-first with a centre dedicated to a new science of cracking-up.

The concept of peridynamics - from the classical Greek words for "around" and "force" - emerged from the United States at the turn of the century.

It uses sophisticated computational models to simulate and analyse these fissures that can mean the difference between triumph and disaster.

But the director of Strathclyde's Peridynamics Research Centre, Dr Erkan Oterkus, says cracks are not always a bad thing.

Teeth create cracks when biting into a chocolate bar

"Think about a chocolate bar," he says. "If you want to enjoy this bar you have to open the package.

"To open the package, what you need to do is tear the package. So you need to create a crack."

So far, so delicious.

"Then your teeth need to split this chocolate bar into smaller pieces. Your teeth are actually creating lots of cracks in your mouth. If you think about it, cracks are everywhere."

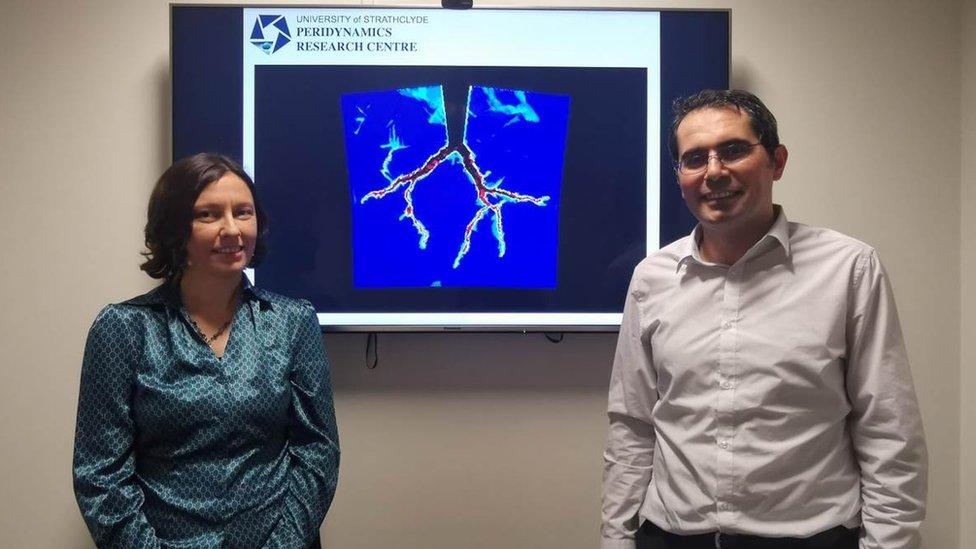

Dr Selda Oterkus and Dr Erkan Oterkus - the co-director and director of the Peridynamics Research Centre at Strathclyde University

Dr Oterkus came to Glasgow from Turkey via Nasa in Virginia. His co-director Dr Selda Oterkus is also his wife.

The peridynamics centre is part of Strathclyde's engineering faculty but it is not all bridges, planes and ships.

Selda explains that they have been working with the Korean giant Samsung to examine cracking in electronic components.

These cracks appear because of steam in unexpected places.

"The electronic package has polymer components," she says.

"During storage and shipping these components absorb moisture. Then during the soldering process, when you want to combine the electronic components together, the temperature rises and it creates vapour pressure - it creates a crack."

High vapour pressure creates cracks in popcorn when you heat it

She has a food-based analogy - popcorn.

"It's the same idea. If you want to make popcorn in your home, it has a shell and it has content in it," she says.

"And when you heat it, the shell gets broken because of high vapour pressure inside."

Other methods already exist for studying how cracks form and spread but each tends to focus on a different scale: very small things or quite big ones.

The computer modelling used in peridynamics means it can be used to simulate cracks of any size in often complex materials like composites.

A fundamental principle is that the same equation can be applied to a material whether or not it has a crack.

One challenge to which it is being applied is global heating.

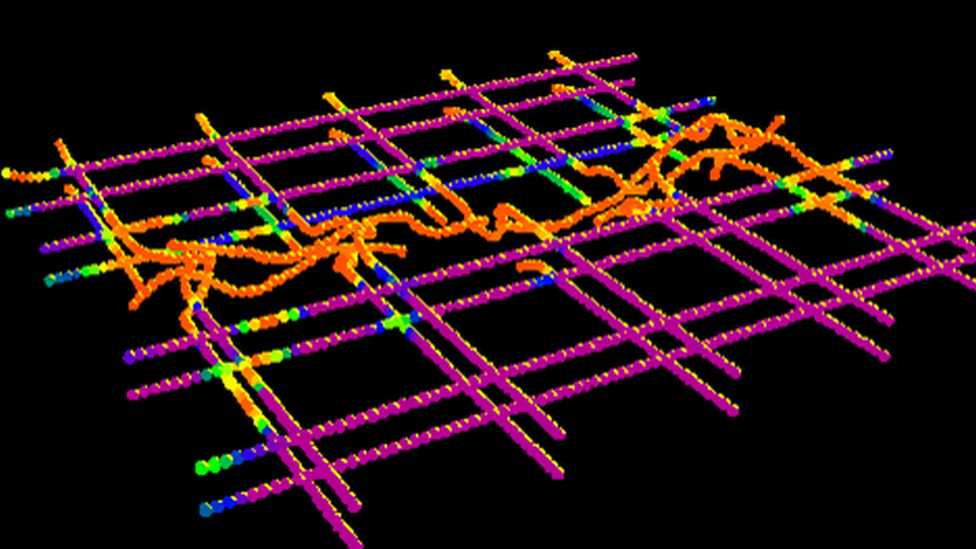

The centre uses computer models to show how cracks appear

As the climate warms it is opening shorter shipping routes between the Far East, America and Europe through seas on the edge of the Arctic.

The sea ice on these northern routes can be cracked but ships can crack too. Peridynamics can simulate the behaviour of both as they interact.

"What we know from history, for example the Titanic accident, is that if we are just designing ships without considering the effect of ice impact, it can create big damage to the ship's structure," Erkan says.

"By using peridynamic methodology we are trying to simulate what is happening in this particular process.

"We are modelling ice as a material and the ship as a material, and we are trying to simulate what happens when these two different objects are in contact with each other."

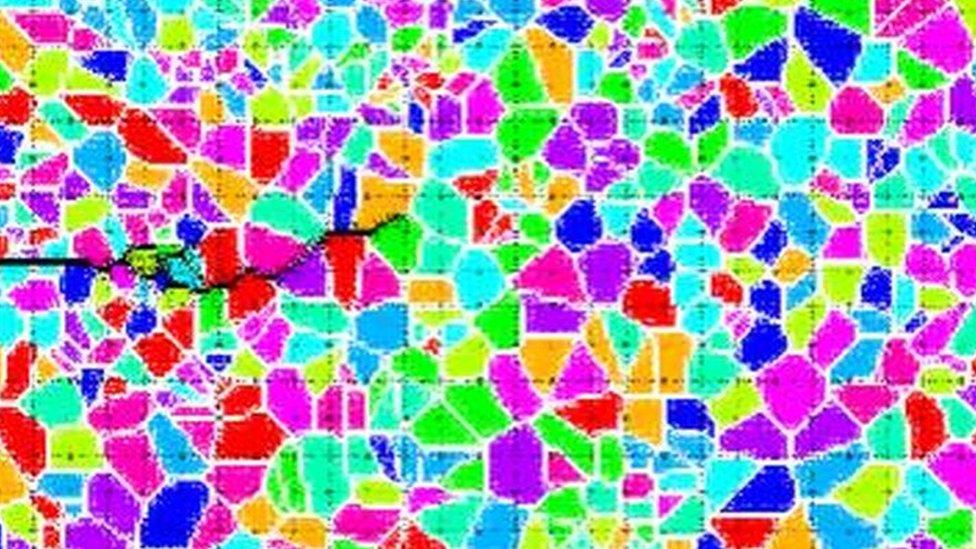

The university studies the many ways in which cracks appear

Peridynamics can also simulate how aircraft behave when they are struck by hail or lightning.

But it can also be applied to softer objects too. Like us.

It can be used to calculate the damage a bullet would do to a human body.

Thermal flows, whether in an aircraft struck by lightning or a cold glass suddenly filled - and cracked - by hot water can be calculated.

The discipline challenges not just existing techniques, but tenets of physics that have prevailed for more than 2,000 years.

The Aristotelian view was straightforward: to move something you must touch it.

That works but it's not the whole story.

Let's say you want to smash a wine glass.

You could throw it at the wall. You've touched it and it's moved - that's what's called a local force.

Or you could just drop the glass on the floor. You haven't thrown it - gravity did the work this time, without touching it. That's a non-local force.

Peridynamics can take account of both types, using the concept of the "horizon".

Not, in this case, the thing behind which the Sun vanishes at night. In this case it's the term for how near or far away a non-local force can be and still have an effect.

The research centre is engaged in a three-year project supported by the US Air Force to find out how well this horizon can be defined.

Peridynamics holds out the prospect of increasing safety by better understanding how forces near and far could affect buildings, aircraft and even our bodies.

In practical terms it could mean the difference between a ship cracking the ice or ice cracking the ship.

Or indeed whether that chocolate bar cracks your teeth.