Why are Scottish councils closing their outdoor centres?

- Published

Outdoor centres like Blairvadach offer activities like hillwalking, mountain biking and climbing

Residential centres across Scotland have given generations of schoolchildren a chance to experience the great outdoors, but yet more facilities are set to close this year. What is behind the decline - and why are people worried about the impact?

Since this story was published, Glasgow City Council announced that it had reversed its decision to close Blairvadach Outdoor Education Centre.

Last week, staff at Blairvadach Outdoor Education Centre in Argyll and Bute were called in for an emergency meeting.

Glasgow City Council officials told them that the centre - one of the largest of its type in Scotland - would be closing in less than four months.

The closure was part of a raft of savings in the council's 2020-21 budget which were due to be announced in a few hours. By the end of the day, the budget was voted through and the centre's fate appeared sealed.

The 44 staff at Blairvadach, on the east shore of Gare Loch, were left shocked by the decision, which quickly sparked a campaign to save the centre.

At many centres, children are given opportunities to explore both land and sea

Glasgow City Council says it is committed to exploring "new, innovative and alternative" ways to offer outdoor learning that "complements" a pupil's education.

But for parents like Ash Loydon, an experience at one of these centres can become a central part of their child's life.

Mr Loydon, an illustrator from Glasgow, has three autistic children who have all gone to Blairvadach for a week-long residential course.

His youngest son, Cassidy, has selective-mutism and uses only about 100 words. Since going to the centre two of those words are "Blairvadach" and "adventure".

"Cassidy was 11 when he went," Mr Loydon says.

"When he came back he kept saying 'Blairvadach, adventure'. He also made a painting of himself at Blairvadach. Two years later, he still talks about it."

Blairvadach opens up activities like kayaking, climbing and gorge walking to all youngsters, whatever their ability and background. The courses are subsidised and no-one's excluded.

Cassidy painted a portrait of himself at Blairvadach

For a parent who is constantly worrying about his son's safety - Cassidy has "no sense of danger", he says - sending your child away to such a centre could be an anxious time.

But Mr Loydon says Blairvadach is one of the few places he would trust to look after Cassidy for a whole week.

"There's something about the staff. You can trust them," he says.

"They treat the kids with respect and they treat them as individuals. It's a non-judgemental environment.

"And at the end of the day, everyone's covered head to toe in mud."

But there is a catch to making these experiences inclusive at a subsidised price, and it's the cost.

Gorge walking near Blairvadach: "At the end of day, everyone's covered head to toe in mud"

Council budgets are increasingly stretched and Blairvadach needs more than £1m a year to run - although its recent accounts show, external the centre's costs are reducing and income is rising, so the net expenditure is much less than that.

Many councils simply don't want the burden of running a fully-staffed, residential centre and all that goes with it and instead use centres run by charities or businesses.

Glasgow's decision to close Blairvadach, which opened more than 45 years ago, mirrors a story that has been repeated across Scotland in recent decades.

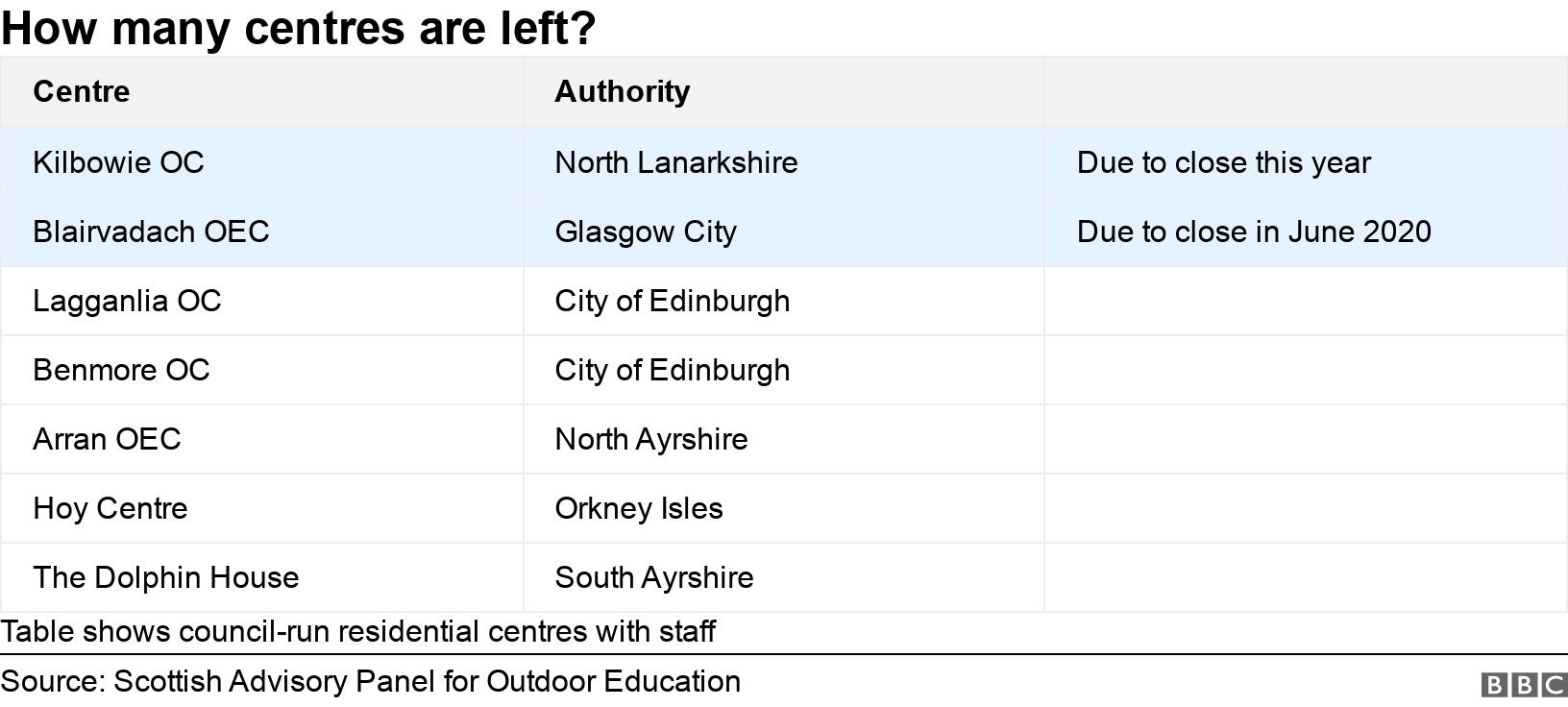

Recent research by the University of Stirling, external found there were 123 residential centres in 1982, more than 70 of them run by local authorities.

By 2018 that had fallen to 64 centres, with less than a dozen owned by councils.

Now there are just seven council centres left, two of which are due to close this year. They are Blairvadach and Kilbowie in Oban, which became a victim of savings being made by North Lanarkshire Council in its recent budget.

Both these closures have sparked a backlash from past and present users of the centres, with petitions to save Blairvadach and Kilbowie quickly reaching more than 10,000 signatures.

Some children in Glasgow already visit residential centres elsewhere in Scotland.

The city council said it planned to move its outdoor education provision to a "Glasgow-based model" in the future, using the city's parks and open spaces while working to ensure "improved and inclusive access for all".

It said this included a "very successful partnership" with Pinkston Watersports Centre which had been running since since 2015, offering outdoor education programmes based around the John Muir Award and National Paddle Sport Awards.

"This has proved a very popular model for our schools with outdoor education opportunities easily accessible during the school day," said the council.

"Uptake has almost doubled in the four years the centre has been operational."

Many centres aim to take children out of familiar environments and give them a different sort of experience

But Robbie Nicol, a former Blairvadach instructor and now a professor of outdoor education at the University of Edinburgh, says that taking children away from their everyday surroundings is valuable in itself.

"Your brain responds in certain ways to certain spaces. It provides different opportunities for learning," he says.

"There's something special about Blairvadach's long association with Glasgow - but it is outside the city.

"It's the idea that you're going away and going to do something different, travelling on the bus somewhere you've never been. Some of the children who go there have never been out of the city before."

Many outdoor instructors will have a story about a child they were able to reach in a profound way, and Prof Nicol is no exception.

He can remember telling a 14-year-old boy from Glasgow they were about to walk up a hill that was hidden in the cloud.

"He said to me 'does that mean I'll touch the clouds?'

"When I said 'yes', he was almost in tears. And these things happen all the time," he says.

Blairvadach costs more than £1m a year to run, but recent accounts show costs are dropping and income is rising

According to Prof Nicol, the "peak time" for outdoor education in Scotland was the late 1960s and through the 1970s, with the decline setting in from the early 1980s.

He's also critical of the commercial sector, which he says "lacks ambition".

"It hasn't been innovative. They rely too much on the thrills and spills and not on the connection with nature," he says.

"We need to focus on what kids can't get elsewhere."

The Scottish Advisory Panel for Outdoor Education has also voiced concerns about the increasing outsourcing of such services., external It believes the "educational quality, employment standards and equitable access to universal provision have often decreased".

Prof Nicol says outdoor education should focus on what children can't get elsewhere

David Fowler, an ex-principal of Blairvadach who retired in 2010, says he has witnessed the decline of properly resourced outdoor education in Scotland.

He had to resist an attempt to shut the centre down in the 1980s because it was too expensive and says he was always aware that outdoor education was a "soft target".

But he believes that well-resourced, council-run facilities are possible - as demonstrated by Edinburgh and North Ayrshire councils that have three big and flourishing centres between them.

Mr Fowler says you can't measure the benefits of a week in the outdoors with tests, but is convinced the impact on a child can last a lifetime.

"When I would give briefings to parents about the residential weeks, I can remember someone coming up to me afterwards and saying their grandson was going to be on the course and there he was sitting over there.

"They can recount the experience they had at the centre years later. It's so long-lasting," he says.

"You're not going to get the same experience in the parks of Glasgow. It's not going to give these kids a greater understanding of the world around them."

All images are copyrighted.