'We need army of volunteers to track down virus'

- Published

Prof Devi Sridhar said ministers should emulate Germany's strategy to "test, trace and isolate"

A public health expert says an army of detectives should be recruited to track the spread of Covid-19.

Prof Devi Sridhar told the BBC the UK was still lagging behind other nations in its response to the pandemic.

She said ministers should emulate Germany which has enlisted medical students and furloughed workers to help "test, trace and isolate".

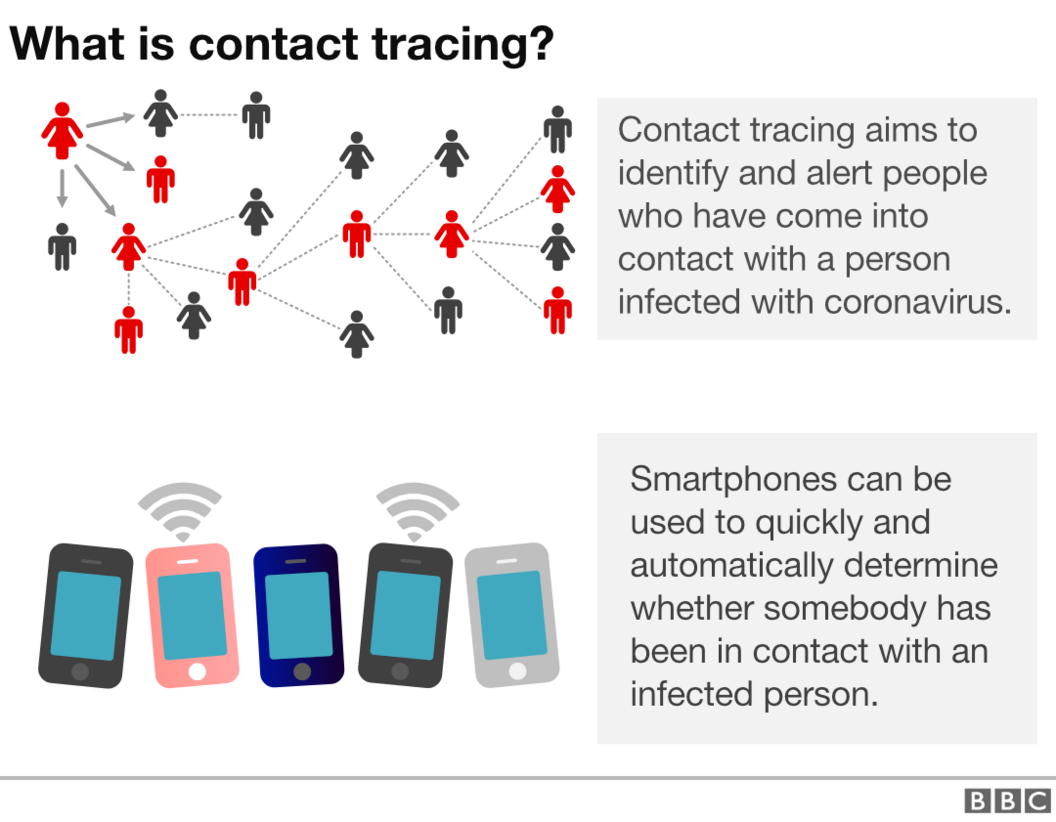

The strategy involves tracking down and quarantining the contacts of everyone who tests positive for the virus.

The aim is to arrest the growth of Covid-19 so that lockdown restrictions can be eased.

"The key here is to keep daily new cases low, because if we keep them low, we can keep a handle on the virus and we can ease other restrictions," said Prof Sridhar, of Edinburgh University.

Prof Devi Sridhar outlined three "paths" for the UK

Surveillance systems already in place for the 'flu including random community testing should be expanded, she said, to track any emerging clusters.

"There's three paths ahead," she explained. "One is we do nothing and a lot of people die.

"The second is we stay in some kind of lockdown and release cycle while all of us slowly get this virus which would destroy the economy."

The third path, which she favours, is to build "complex and massive" public health infrastructures" to "keep a handle on this virus".

"It requires a lot of people, contact tracers, almost like a whole workforce," she said. "Germany has recruited thousands of people just to do this."

"People are willing to volunteer. They want to help find a solution. And so if we can use that and actually train people and start getting that up and running, that would be a major step forward."

Prof Sridhar said smartphone apps which use Bluetooth technology to detect when a user has been in proximity with an infected person may be "a little bit" useful.

However she cautioned that too few people downloaded them in Singapore to make a major difference.

Prof Sridhar - who is chair of Global Public Health at Edinburgh University - is also a member of an expert group advising the Scottish government on its response to the pandemic.

She also chairs a Royal Society working group analysing Covid-19 data, whose findings are reported to the UK government's chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance.

Even with a comprehensive contact tracing programme in place, Prof Sridhar said physical distancing would be with us for a long time.

She said: "I think we're going to have to alter our behaviour in terms of having mass gatherings, concerts for the next year, year and a half until we know more about this."

What is Scotland's strategy?

Prof Sridhar said testing in Scotland needed to be ramped up dramatically from a current Scottish government target of some 3,500 tests a day to a range of 15,000 to 20,000.

Earlier this week the First Minister told MSPs that target was one she broadly recognised, adding that the assessment of the number of contact tracers would depend on what social distancing measures were in place.

Nicola Sturgeon signalled that she would publish a detailed paper on her government's test, trace and isolate strategy, "probably early next week."

The overall UK government target is 100,000 tests per day, a proportion of which is being carried out at sites in Scotland.

Early decisions 'did cost lives'

Assessing the breadth and depth of testing in Scotland is complicated by the fact that both the Scottish and UK governments are running their own testing centres with different eligibility criteria.

Prof Sridhar was an early critic of the UK government's plan to, in the words of Sir Patrick, "build up some kind of herd immunity" — in other words to let the virus spread through the population until it ran out of people to infect.

The concept, endorsed at an early stage in the outbreak by Scotland's national clinical director Jason Leitch, external - but since disowned by both London and Edinburgh - was always a "terrible idea," without a vaccine to protect the most vulnerable, she said.

"The real big difference between the UK as a whole and other countries is that we stopped contact tracing and we stopped containment in early March," said Prof Sridhar.

"What really surprised me was the [12 March] decision to stop testing for minor symptoms and to stop contact tracing, as well as to let mass gatherings go ahead and to let non-essential travel go ahead."

"We had the benefit of time. We knew where this was going."

On the question of whether those early decisions cost lives, Prof Sridhar says they did - and "probably did result in the virus spreading heavily throughout the UK".

She said: "Those early weeks when we didn't lock down early, we didn't do aggressive containment.

"We're in a difficult position because now we've basically got to put the genie back in the bottle."

- Published27 April 2020

- Published20 April 2020