The people who die alone with no one to mourn them

- Published

When people die alone, with no obvious next of kin and no will, a small team of public servants steps in to help

I am alone at a funeral for a woman I have never met.

My only company is a plain pine coffin and two bouquets of flowers. One is from a friend recalling "many happy memories over the years"; the other is from a niece who never met her auntie.

There is muzak but no minister, so no final words for 67-year-old Carol (not her real name). The service is over in less than seven minutes.

Carol died alone, with no obvious next of kin - and no will.

When that happens in Scotland, cases are investigated by a small team in the national prosecution service, external. The Ultimus Haeres Unit (last heir in Latin) tries to find blood relatives, along with any assets that may be left.

I followed the team as they worked to piece together the lives of people like Carol, and make sure they are laid to rest - even if there's no-one there to mourn them.

'You feel the person is there watching you'

The UHU investigators wear forensic suits in order to minimise their impact on the property

At Carol's one-bedroom flat in a traditional Glasgow tenement the only sound is the swishing of the forensics-style white plastic overalls as UHU investigators Katy and Yvonne go about their work.

The two-hour search is diligent and painstaking, with everything in the flat returned to its original place when they are finished.

"In a sense you feel the person is there watching you," says Katy.

The main aim is to find a will, but the team are also looking for anything that helps find a bloodline relative or a friend who might be able to give them "a piece of the jigsaw".

Photos are carefully removed from frames to check for any writing on the back. Biscuit tins are checked and empty suitcases are opened. These are all places where investigators have found clues in the past.

Signs that she had lived a full life are peppered around Carol's cluttered flat.

Photos with smiling people her age and younger; an old passport with stamps from around the globe; snorkelling equipment found at the back of a wardrobe.

"She looks as if she's had a good life. I'd love to have spoken to her," says Yvonne.

A full ashtray and an open TV guide in the living room are clues to how suddenly Carol fell ill.

"That coffee cup is full, like she'd just made it before she went to hospital," says Yvonne.

One curious discovery is a passport for a man from The Gambia, which is found on the living room couch.

Checking the post can help establish whether a person had bank accounts and any other financial assets or debts

Cash and valuables are collected and logged for the long process of settling Carol's estate.

When the search moves to her bedroom there is another intriguing discovery - a photo, hidden in an underwear drawer, of Carol on what looks like her wedding day.

Katy and Yvonne are dwelling on this find when there's a knock at the door - it's the owner of the Gambian passport.

The man explains he's a friend of Carol's and is "the guy who came to look after her every day".

He wants his passport back and says his TV is in the flat too. He only leaves with the passport.

"He didn't ask about the funeral," Yvonne points out.

The search for a will is fruitless, but clear plastic bags full of files, photos and letters are gathered up and taken back to the office.

The next part of the job takes months - death administration is notoriously slow - and involves a flurry of letters and phone calls to a range of public and private agencies.

Contact is made with social workers and the housing association, and a friend is traced. But, as is often the case, the full picture evades investigators.

It is established that Carol was not a native of Glasgow. Items in the flat had suggested that she had a son - but this is never confirmed.

The investigators eventually trace a niece in another part of the country, who never met Carol. She is the only living bloodline relative, but wants nothing to do with the funeral.

None of the people smiling alongside Carol in her photos come forward either.

'He was a man about town, he was a playboy'

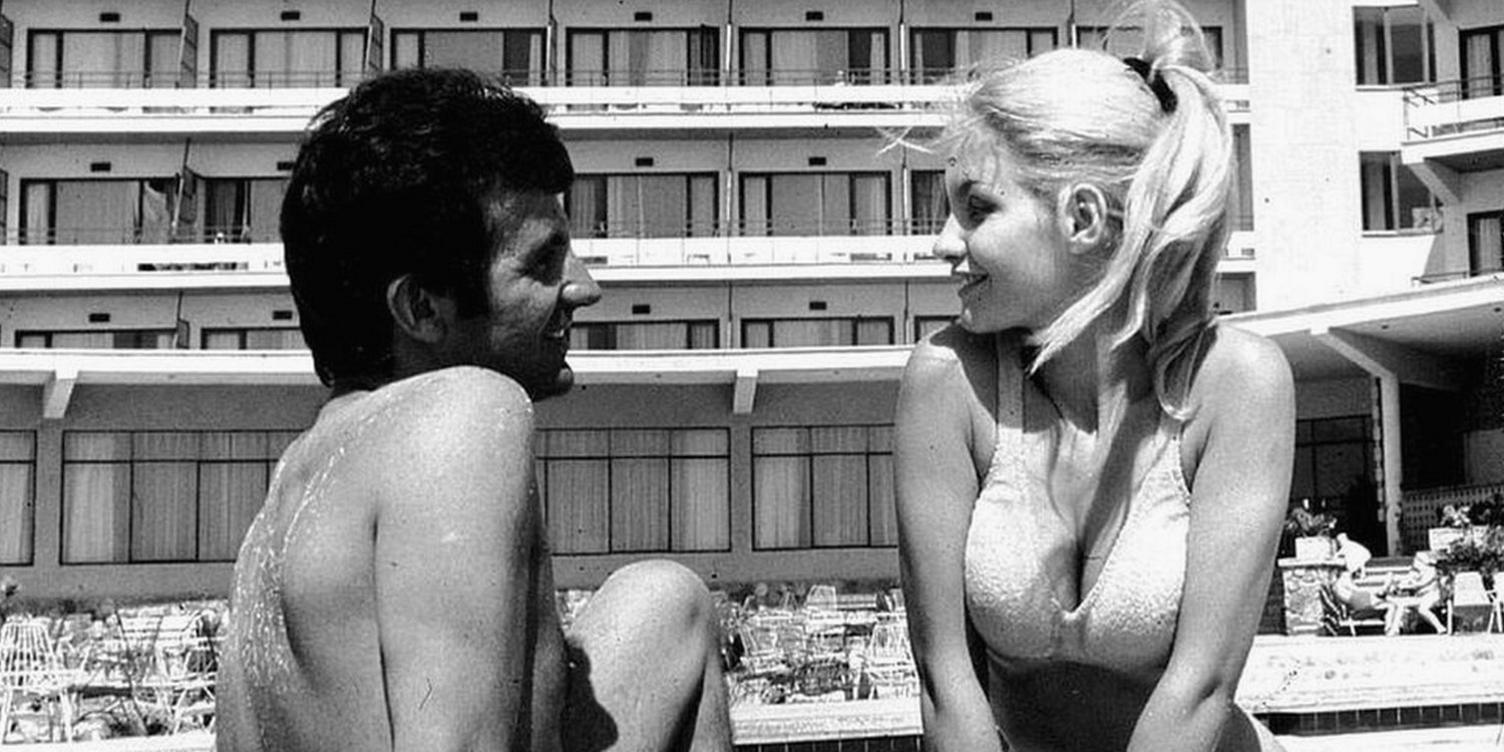

Robert on holiday in Spain with an unidentified woman. This was one of a number of pictures of Robert, some of which looked professionally taken, with glamorous-looking women

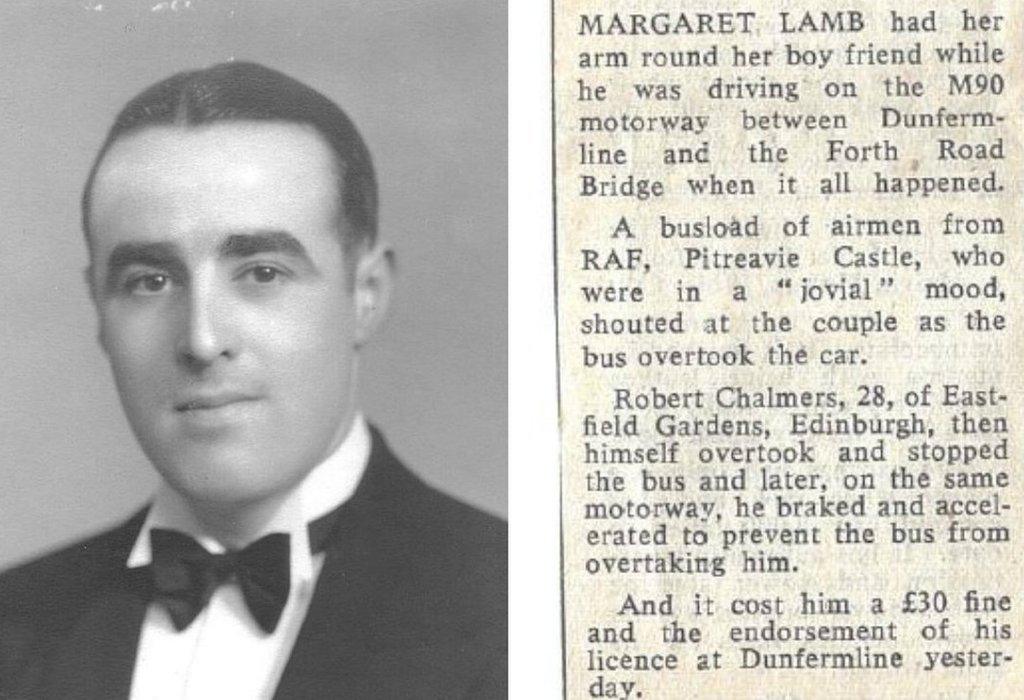

Robert Chalmers died alone in an Edinburgh hospital last April, just days before his 75th birthday.

For the hospital staff and then UHU investigators trying to piece his life together, there was initially little to go on.

But a public notice asking for relatives to come forward attracted the attention of genealogy firms, who traced Janet Bishop.

Robert was her mother's cousin - and, by coincidence, Janet is one of the country's top professional genealogists.

"My mother had spoken about him," she said.

"I knew he was the only one who had done better than the rest, but I didn't know anything else about him," said Janet.

"When I realised he had died and nobody knew anything about him I was intrigued. It came out he had not left a will - it was a bit strange."

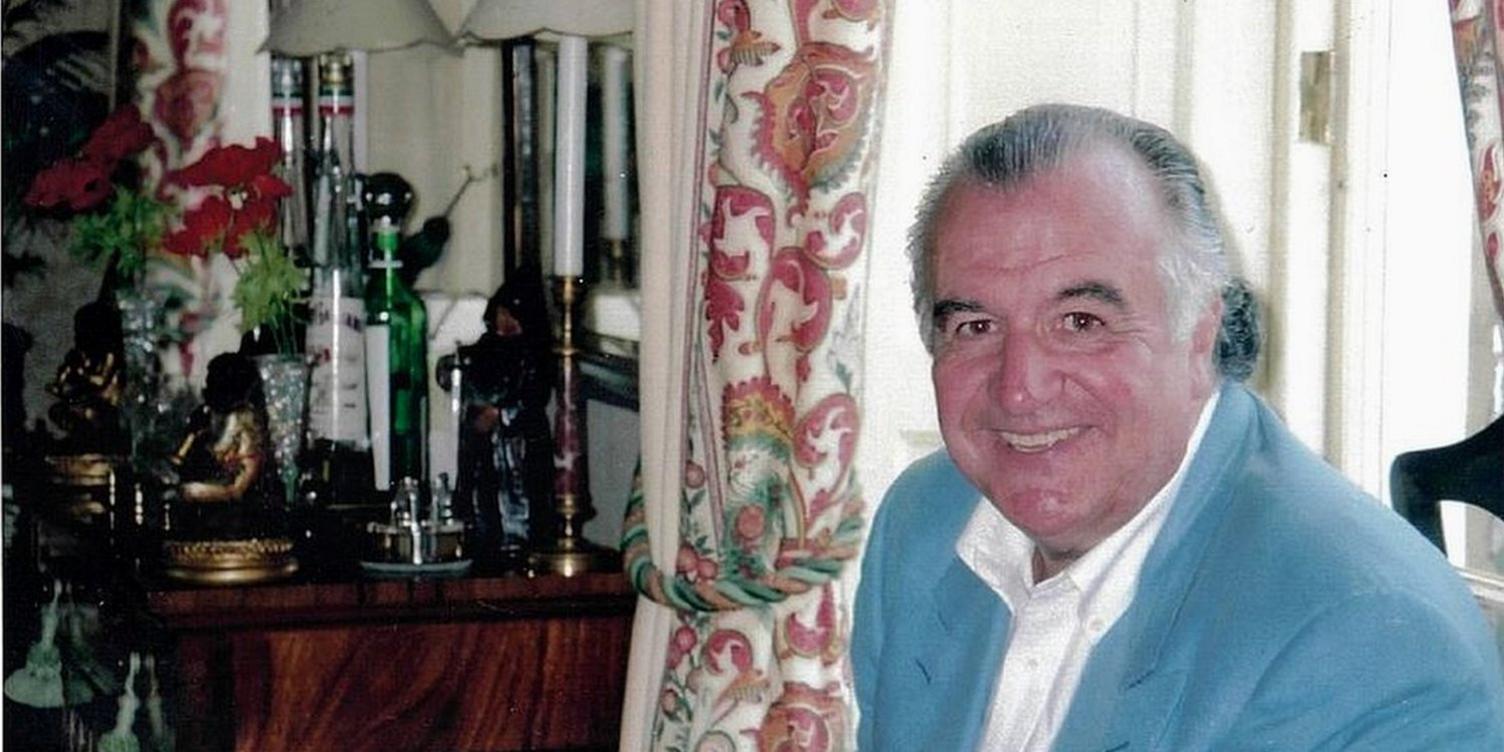

Robert's well-appointed flat in the plush New Town area of Edinburgh was full of clues to his life. It contained art, antiques and expensive watches.

But for Janet, who was appointed executor for Robert's estate, it was a cache of photographs and newspaper clippings which really caught her attention.

"I pieced together what I think was his life and he was obviously part of 'the set'," she explained.

"He would go to the places to be seen in Edinburgh, him and his pals around the New Town."

Robert had his own flooring company and lived alone in Edinburgh's New Town

Janet was particularly interested in a leather wallet with polaroid and passport-style photographs of what were assumed to be a string of Robert's ex-girlfriends.

"He was a man-about-town, he was a playboy," she says.

"Never married and had loads of girlfriends by the looks of it. He enjoyed the good things in life."

Friends and neighbours helped fill in some of the blanks. Robert was educated at a prestigious local private school and made his money through his own flooring company.

Janet was also told Robert was friendly with former England manager Terry Venables, and looked after George Best when he was living in Edinburgh and playing for Hibs in 1979.

His father had died when he was in his 20s and Robert was close to his mother. After she died it seemed, according to Janet, that it may have been easier for him to tell people he didn't have any family.

"He knew they were there, so to say to his friends 'I don't have any family' - that's not true," she says.

"What he meant was he didn't have any contact with them any more, but everyone has family, whether you like it or not."

A picture of what is thought to be Robert's father and a newspaper clipping Robert kept of a time he got into trouble with the police

Robert's flat has now been sold. Any money left over when the estate is settled will be split among his distant blood relatives.

But Janet doesn't think that is right.

"Whatever money he had is going to the wrong place now because he didn't say what he wanted to do with it," she says.

"The people who benefit, if we benefit at all, we are only entitled because the law says so.

"We did not know him, we gave him no help so why should we be entitled to anything?"

Janet says learning about Robert's life shows that people who die alone do not always do so in sad or difficult circumstances.

"Each to their own," she says. "I just wish he'd made a will."

'Before he was a name, now he's becoming a person'

Gerry's case was passed to the UHU after social services and the hospital could not find any family members.

The 85-year-old had fallen ill after moving from his housing association flat in Glasgow to a care home. Gerry (not his real name) was an organised man, which made the investigators' job easier.

A series of notebooks in his home detailed his financial affairs, as well as his meals. Corned beef was popular on Wednesdays.

Safe boxes in his wardrobe were found to contain £16,000 in cash.

"Before he was a name, now he's becoming a person," says Yvonne as she sifts through a box of old letters and Christmas cards.

Gerry had stored £16,000 in safe boxes in the back of his wardrobe

Gerry's organisation extended to a funeral plan and instructions for him to be buried at the family lair with his parents.

Retired locum minister Graham Morrison was asked to say a few words at the graveside for Gerry but he does not have much information to go on as he prepares for the short service.

"You do what you feel is right at the time," he said.

"It has to be done with the same respect as anyone else. It doesn't matter how many people turn up. This is about a person's life and the respect that has to be given.

"It could be any of us in these circumstances, but for the grace of God."

Graham has decades of experience of these types of funerals.

"I've done a full service for a homeless person, for people who were alone with no-one in the world," he said.

"Actually, I put a lot more effort into it if I'm honest."

UHU investigators work in pairs when conducting searches

As we approach the graveside, we have unexpected company.

A cousin, who never met Gerry, was traced that morning by the UHU and has come to pay their respects.

The windswept service at the graveside is short but meaningful. The lilt of Graham's Outer Hebrides accent feels tailormade for the occasion.

After the funeral, Gerry's estranged daughter is eventually traced and his estate is settled.

But the full story of his life, like why Gerry was estranged from his daughter, is never told.

'You're doing the right thing when nobody else is there'

Duty and dignity are the watchwords of Ella Harkin, who manages the Hamilton-based UHU.

"You never know how things are going to end," she says.

"You could have loads of family around you and then one day you're just yourself.

"These people have died and they have got no-one. The way I look at it is that they set up this unit to be that one.

"It's not even about money. It is about making sure they are put to rest respectfully."

Katy echoes the sentiment. "You're sad for that person, but in a sense you are doing the right thing for them when nobody else is there."

The team's daily work is littered with difficult conversations.

This can include breaking the news of someone's death, or explaining to a friend or a step-child that only bloodline relatives can benefit from an estate.

Yvonne says piecing together a life and tracing next of kin is what makes the more harrowing searches worthwhile.

The increasingly digital nature of the way we live our lives is creating new challenges for the UHU

The workload is growing. The unit dealt with 540 cases last year, a 66% increase on 2016-17, with cold winters and hot summers thought to be factors in that rise.

And the investigations themselves are gradually getting more difficult.

The shift towards conducting our lives online is actually making it harder to trace the lives of the dead.

The biscuit tins crammed full of important paperwork or battered personal phone directories are becoming rarer.

"For us to get that sort of information, we need more tools at our disposal," explains UHU manager Ella.

"Ten years from now, if we don't keep up, it will be harder for us to do our job. We need to adapt to the changes in society."

But what is likely to remain the same is how so much of the UHU's work can be traced back to the devastating impact of a breakdown in relationships.

"It is a shame, but it gets to that stage where sons and daughters don't speak to parents and vice versa. I think people always think there's time to make up, and now there's not," says Yvonne.

"People don't realise life is far too short for petty arguments."

(Some names have been changed to protect the deceased's anonymity)

A 30-minute documentary about Next of Kin can be heard on BBC Sounds

- Published7 September 2020

- Published9 April 2017