Covid in Scotland: What's helping us to understand the new rules?

- Published

Pubs in the central belt of Scotland have had to close under new government measures

Last week the Scottish government published the evidence, external that guided the issuing of strict new measures. But does it bear up to scrutiny?

The 14-page report, containing a mix of confirmed case data, poll responses, and track and tracing figures, helped to inform the policy of closing pubs and restaurants in a big area of the country.

There is no question that the latest infection and death figures illustrate a resurgence of coronavirus in Scotland.

'Huge implications'

But Dr David Paton, chairman of industrial economics at Nottingham University's Business School, believed evidence presented in the government document failed to adequately vindicate the restrictions placed primarily on the hospitality sector.

He argued: "There's no sense of proportionality, Shutting down hospitality is quite unprecedented and extreme with huge implications for livelihoods, jobs, and public revenue."

Dr Paton said restrictions might previously have been considered in emergency situations when deaths and hospitalisations were spiralling out of control, and not when coronavirus-related deaths are averaging below three per day.

But the Scottish government has insisted that no measure had been "imposed lightly" and that moves were proportionate and always under review.

A spokesman said: "The scientific evidence around transmission highlight that the biggest risks are associated with close contact with an infected individual for a prolonged period of time, and we know that often comes from household mixing.

"We know that household mixing for an extended period of time can also happen in hospitality environments and 20% of positive cases have some link to pubs and hospitality".

The report ties an increase in the R number to the re-opening of pubs and restaurants on 15 July with an acknowledgement that "this cannot be entirely attributed to" the hospitality sector, and that the data doesn't necessarily "indicate where people who have tested positive were infected".

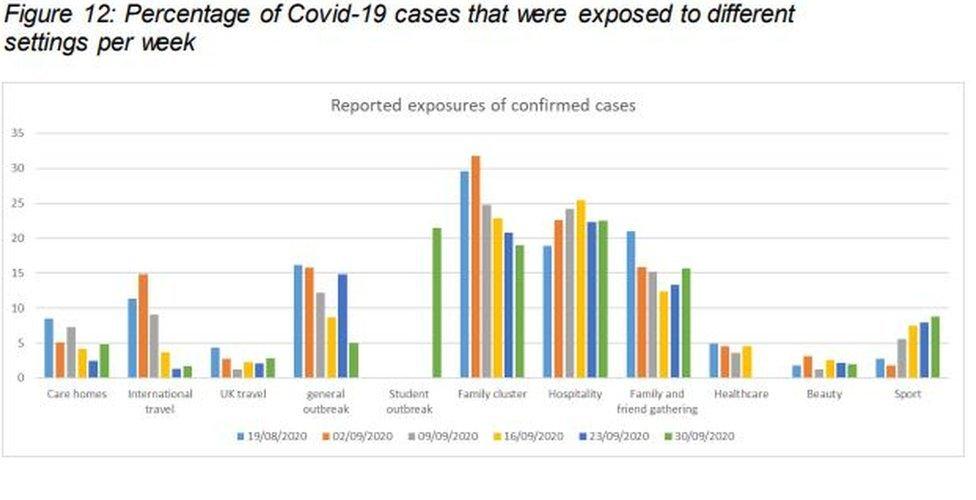

A graph in the document shows where the percentage of individuals visited within seven days of their symptoms developing or receiving a positive test.

A graph of different settings for transmission, taken from the Scottish government's science document

So, what does it tell us? The data shows a decline in positive cases linked to hospitality over the last two weeks and it illustrates that cases are increasing weekly in other settings such as sports and the gathering of friends and families.

The evidence paper also included Test and Protect data showing that the percentage of those testing positive who had reported hospitality exposure had risen to 26% by the start of October.

But the report does not give details on exposure to the virus in other settings like shopping centres, buses, ferries, supermarkets, offices, schools, factories, gyms or places of worship.

Linda Bauld, professor of public health at Edinburgh University, said "it's not as simple as counting settings" when trying to pinpoint ground zero for transmission hotspots.

She explained: "People are likely to spend longer in a pub or restaurant than in a shop, for example, and there is more face to face contact without face coverings on when people are eating and drinking.

"It's also very much the case in other countries that case numbers and clusters have been linked to hospitality venues, unfortunately."

What other data helps our understanding?

Aside form the Scottish government's science paper - written by Chief Medical Officer Dr Gregor Smith; Chief Nursing Officer Fiona McQueen and National Clinical Director Jason Leitch - is there other data which helps form a more complete picture?

Last week analysis from Public Health England, external said 14,826 people testing positive were referred to NHS Test and Trace, and reported at least one event within the transmission period.

And what were the most common activities? Shopping (13.3%) and eating out (13%). Could those findings be reasonably applied to Scotland too?

After the easing of lockdown in July and August, Google mobility data, external showed an increased use of public transport, retail and recreation in cities like Glasgow and Edinburgh.

So if we see more activity around retail and leisure, why were restrictions not extended to shopping centres, museums and libraries?

If we go back to Scotland's science paper, it highlights hospitality as the primary setting for people, from numerous households, gathering in a small space for prolonged periods of time, eating, drinking and conversing.

The counter argument from the hospitality sector is that they are good at "policing" their premises - no music, wearing masks when standing, one way systems to the toilets and time limits on visits are the core measures many have put in place.

There have been notable outbreaks among students at various campuses in Scotland

Dr Paton, who has warned of the economic impact of bringing back lockdown measures, said the Scottish government's report "seems to be selectively using and reporting data to bolster the case for more restrictions".

He explained: "[For example] the paper has chosen to model the most extreme scenario possible suggesting infections could go up to over 35,000 per day in November. Their modelling would be suggesting cases go up to an unprecedented level, not seen anywhere in the world."

But Prof Bauld has argued that the government's evidence is not based on "speculation".

She said: "It's a combination of association with general evidence about how we know the virus spreads, and the risks associated with different environments from studies in the academic literature to date."

However, the fact is - and as the evidence itself confesses - we still don't know for certain where people are being exposed to the virus.

LOCKDOWN: Six months that changed our lives

NUMBERS: Four key figures to watch out for