Covid in Scotland: How much longer will lockdown last?

- Published

- comments

The first minister has confirmed that Scotland will be in full lockdown until "at least" the end of February.

Nicola Sturgeon said the current restrictions were working, but added the level of Covid infections clearly remained "too high".

How much progress does Scotland need to make before lockdown can begin to be eased?

Measuring the epidemic

Scotland's national clinical director, Prof Jason Leitch, has talked about using World Health Organisation (WHO) indicators when calculating the level of Covid-19 transmission in the country.

He told BBC Scotland this week that the Scottish government was aiming to get the number of cases below 50 per 100,000 people and the percentage of people testing positive under 5% before it would consider relaxing restrictions.

Doing both of these things would put Scotland in the WHO's "level 2" category of community transmission, where it's judged there is a "moderate incidence" of locally acquired infections.

The WHO's seven categories range from "no active cases" to "level 4" community transmission, when the general population is at high risk of being infected.

In the organisation's guidance on implementing measures to control Covid-19, external, the WHO also lists two other ways of calculating the levels of Covid in a population: hospital admissions and death rates.

Governments using this guidance will balance these indicators against the other health harms and economic impacts caused by lockdown measures.

It's also likely the Scottish government would want to see rates remain below the WHO thresholds for sustained periods, rather than briefly dipping below the line.

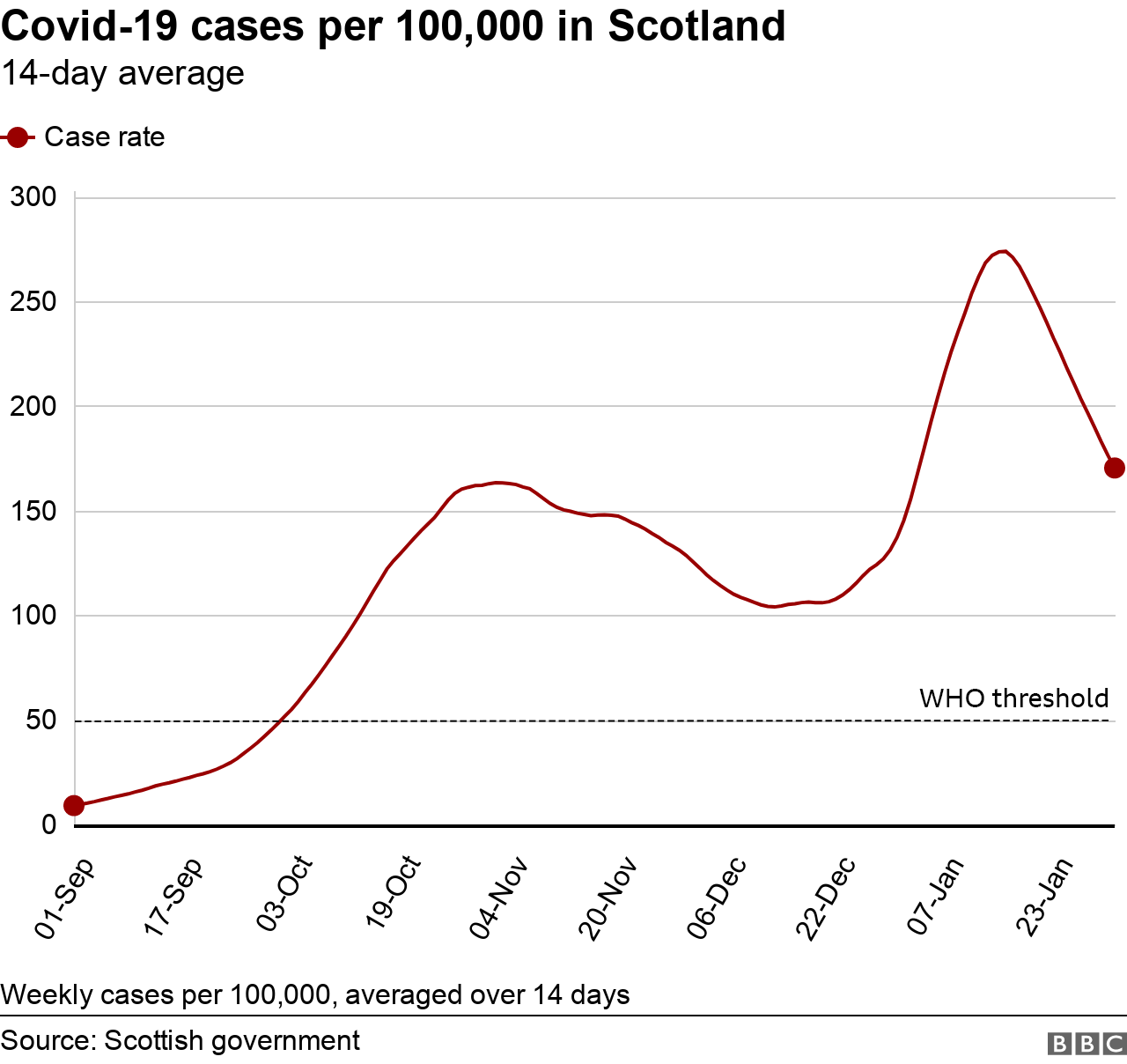

1. The number of cases per 100,000 people is much too high

The WHO advises governments to look at their weekly confirmed cases per 100,000 people and then average the figure out over a 14-day period.

By this measure, Scotland had a rate of 165 cases per 100,000 people on 2 February.

There's been a sustained decline in this figure since the middle of January, but the rate is still well above the WHO's level 2 threshold of 50.

The last time Scotland was below 50 cases per 100,000 was at the beginning of October.

It's difficult to compare this rate with the first outbreak in the spring as there was no mass testing earlier in the pandemic.

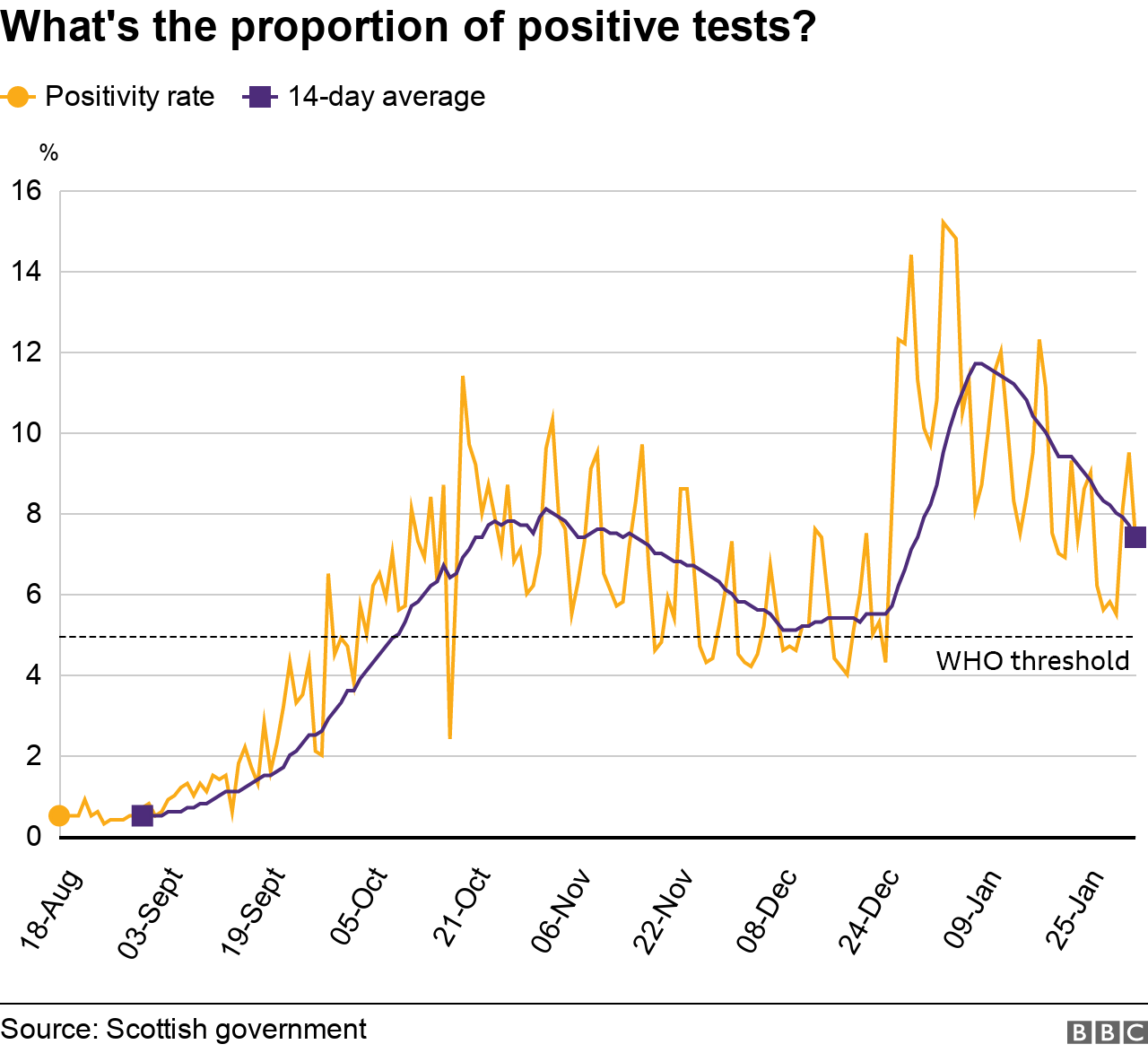

2. The percentage of positive tests also needs to come down

The Scottish government measures the positivity rate by dividing the number of positive tests per day by the total number of tests carried out.

The figure it's aiming for is 5%, which again would put Scotland in the WHO's "level 2" of community transmission.

Like infection rates, the number is declining, but there's still some way to go.

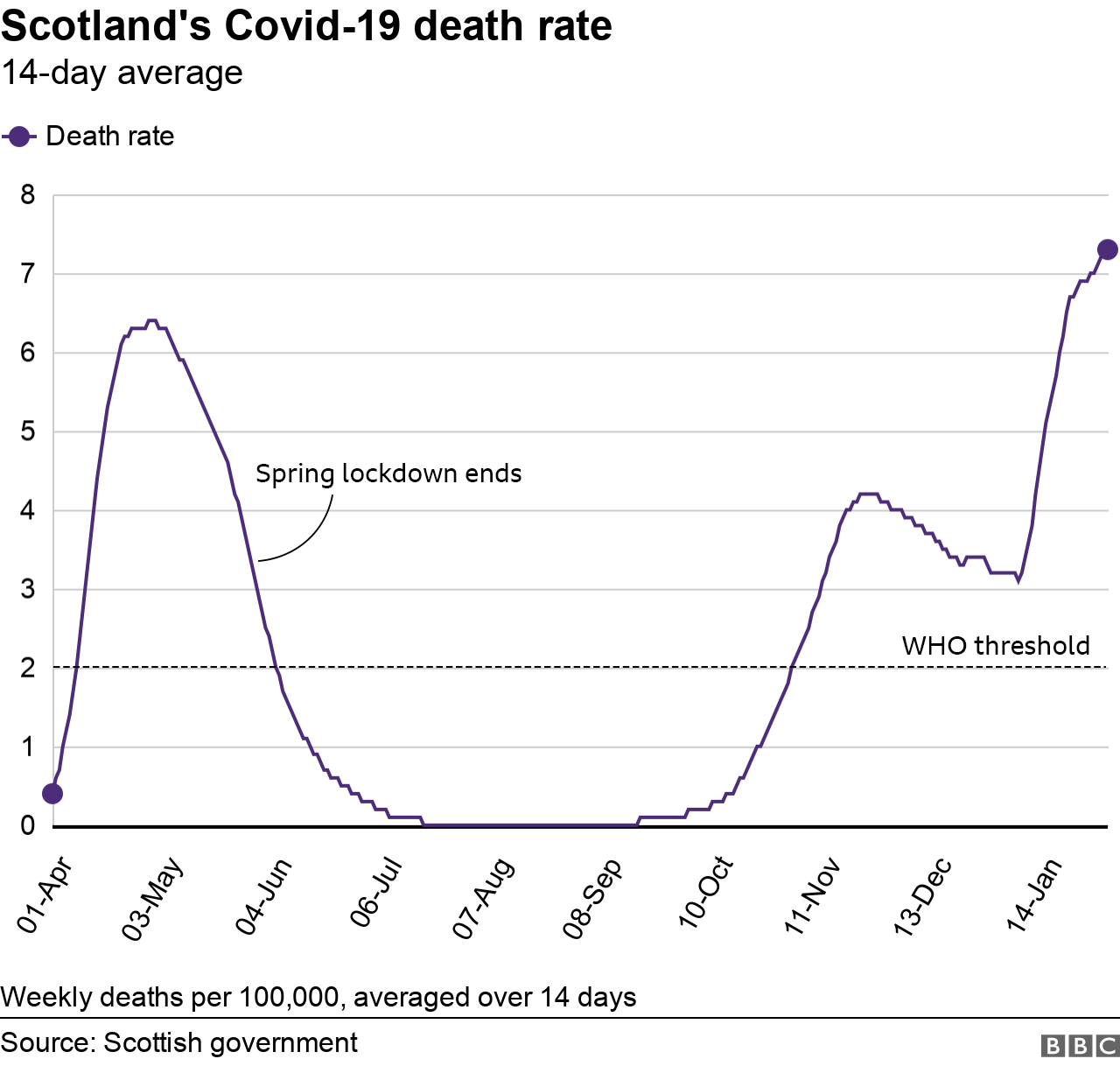

3. The death rate has not begun to decline yet

The WHO says governments should look at the number of weekly deaths "attributed" to Covid-19 per 100,000 people and average them out over 14 days.

A death rate of two per 100,000 people or less needs to be achieved to indicate "level 2" community transmission, according to the WHO.

This chart counts deaths in Scotland within 28 days of a positive test for Covid-19. If the wider definition of all death certificates mentioning the virus were used, the rate would be slightly higher.

The rate in Scotland is currently just over seven and has not yet begun to decline.

The full lockdown in the spring ended on 28 May, although the easing of restrictions was phased over several weeks during the summer.

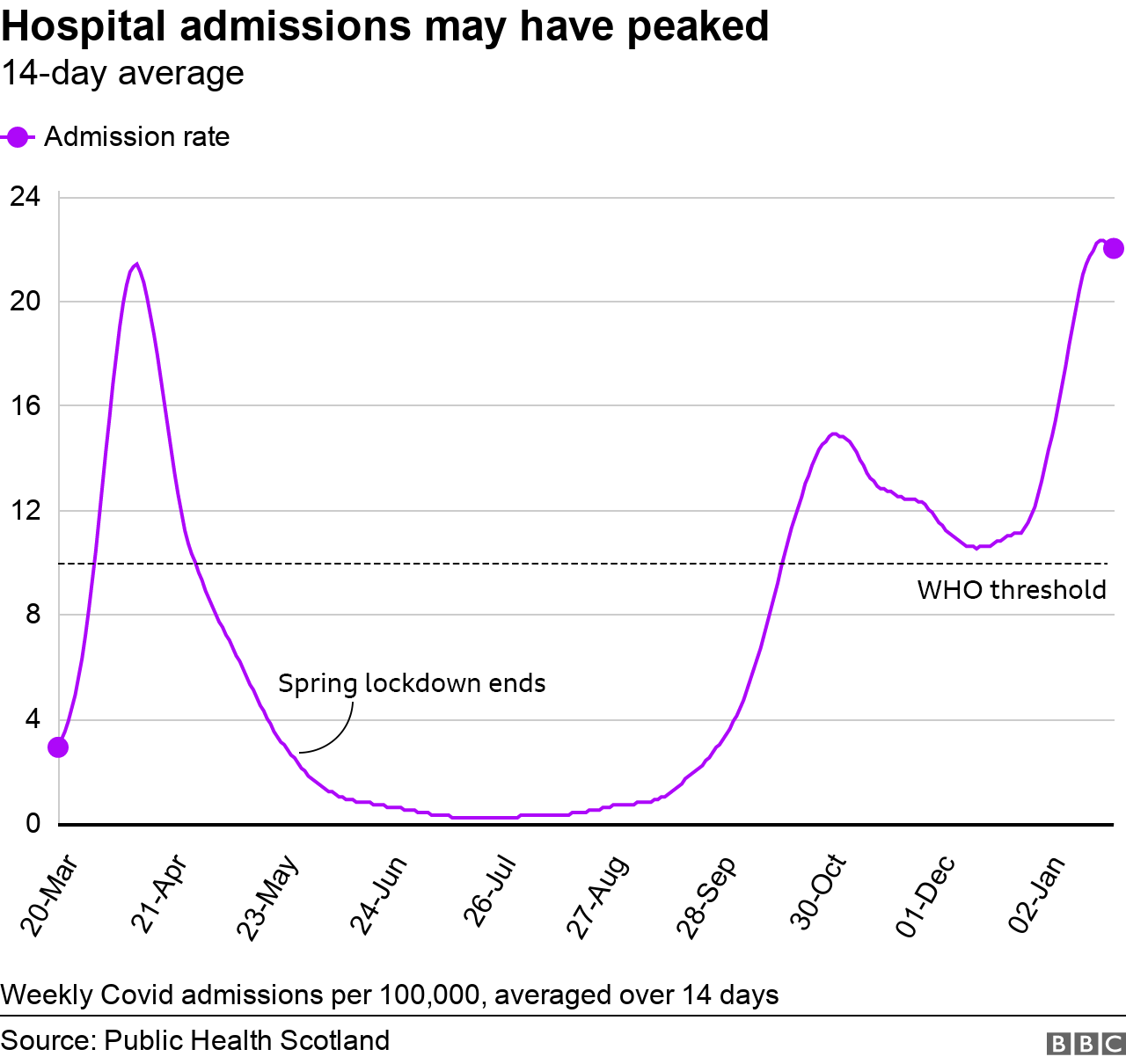

4. Will hospital admissions begin to fall soon?

Figures on Covid-19 hospital admissions are currently available up to 22 January, when the 14-day average of weekly admissions was 22.

The WHO threshold in this instance is 10 cases per 100,000.

The 14-day average has not yet begun to decline significantly, but daily admissions appear to have peaked on 11 January, according to Public Health Scotland figures, external.

In the spring, the decline in infection rates was followed by a decline in hospital admissions and finally a fall death rates.

If this pattern is repeated, then a corner may have been turned in this second wave - but there is still a long way to go before the rates of infections, hospital admissions and deaths are where the Scottish government would like them to be.

5. The vaccine needs to reduce illness

In the world race to vaccinate, Israel is out in front after giving first jabs to more than half its adult population. So, what are we learning from their mass vaccination programme?

Assessments by the Israeli Ministry of Health (MoH) report signs that infection and illness in the over-60s is being driven down. The fall appears to be most pronounced in older people and areas furthest ahead in their immunisation efforts. This suggests it is the vaccine, and not just the country's current lockdown, taking effect.

The MoH data suggests infections and illnesses fell consistently from 14 days after receiving a first jab onwards.

In Scotland just under 14% of those aged over 16 have had an injection with England at more than 18%; Wales at nearly 17% and Northern Ireland at 15.59%.

Infectious disease specialist Dr Susan Hopkins told the BBC's Andrew Marr programme on Sunday that the UK should see its vaccination programme, which began on 8 December, reducing Covid illness within the next fortnight.

While the current vaccines are said to be highly effective in preventing severe sickness in individuals there had been less assurance over whether they could prevent virus transmissibility. However, early research on the Oxford-AstraZenenca vaccine points to good news.

The results of a study, which has not yet been formally published, external, suggest that the vaccine may have a "substantial" effect on transmission of the virus.

It means the jab could have a greater impact on the pandemic, as each person who receives it will indirectly protect others too.

As well as showing an effect on transmission, the study found the vaccine offered 76% effective protection from a single dose for three months.

Do you have a question about the Covid restrictions in place in Scotland? Use the form below to send us your questions and we could be in touch.

In some cases your question will be published, displaying your name, age and location as you provide it, unless you state otherwise. Your contact details will never be published. Please ensure you have read the terms and conditions.

If you are reading this page on the BBC News app, you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question on this topic.

- Published2 February 2021

- Published13 January 2023