Oil major shifts to minor key

- Published

Shell is among several major oil companies trying to find a route from heavy dependence on the black stuff for big dividend payouts, towards a greener future.

Its new strategy holds firm on current production levels of oil and gas, and takes some big bets on being able to mitigate that.

Not following the path of its rivals, towards a big bet dependent on renewable energy investment, it is taking an approach focused more on the customer, the retail and the service end of its business.

This is a time of unprecedented challenge to the old ways - disease control, curtailed travel, the digital economy, automation of jobs, voters in revolt, and, not least, tackling climate change.

Some are going to be swept out of the way. Oil and gas producers are trying to find a way to ensure they're not among them, and can instead catch the tide.

The easy bit is declaring your company is now about "energy". Several companies have set out their intention of becoming big in wind and solar power. But these are capital-intensive and not high-margin.

Much more difficult is reducing the dependence on oil and gas for generating shareholder returns.

Royal Dutch Shell is the latest to set out its vision and targets. In a lengthy presentation by chief executive Ben van Beurden on Thursday, one word that only snuck out on two occasions (that I noticed), was "oil". It seems to have become a dirty word, more commonly referred to as "upstream".

Shell currently operates 44,000 petrol stations in more than 75 countries

The company is prouder of its leading position in gas, arguing it is a necessary alternative to coal, a baseload back-up for intermittent renewable power and replacing oil burn in shipping. Its scenario-planning foresees LNG (liquified natural gas) growing at 4% per year up to 2040.

Adding together oil plus gas, rising to 55% of the joint total, production is on track to remain steady through this decade, and to be the main way of sustaining and growing dividends into the 2030s.

Energy parks

You're more likely still to hear talk of transition. And while the aims are lofty and the time horizons are distant, that still leaves a long tail of attachment to the old ways.

Having peaked in 2019, Shell's oil production is expected to fall by 1% to 2% each year. Some big new projects will get backing until 2025, and after that, there will be no new frontier projects, but a lot will continue pumping.

The company is retreating from several oil basins, including Nigerian onshore, which has brought a barrelful of cost and reputational damage. Divestments are targeting $4bn per year. Only nine core regions will be retained - the UK's offshore sector being one of them.

Other assets will be sold off, almost always to companies without such a consumer reputation to protect, less exposure to fickle public shareholders, and fewer qualms about carbon footprint.

With the oil majors reducing their presence in UK waters, asset ownership by lesser-known, private-equity or sovereign-backed, late-stage specialist drillers is now a feature of the UK North Sea.

But Shell is trying to take on responsibility beyond its drilling.

With 14 refineries (reducing to six, to be known as "energy and chemical parks") and a huge worldwide retail arm, it retails three times more oil produced by others than it produces itself.

Plug-in points

The intention is to reach net zero carbon by 2050, including all the other oil and gas that it sells. The boss says that, by mid-century, he doesn't want to be selling to anyone who isn't mitigating the climate changing effects of burning it.

So Shell's approach is to focus on marketing, to innovate with new premium products, to improve energy efficiency, to recycle plastics, and to become a service company to customers who are willing to pay to offset their climate-changing impact.

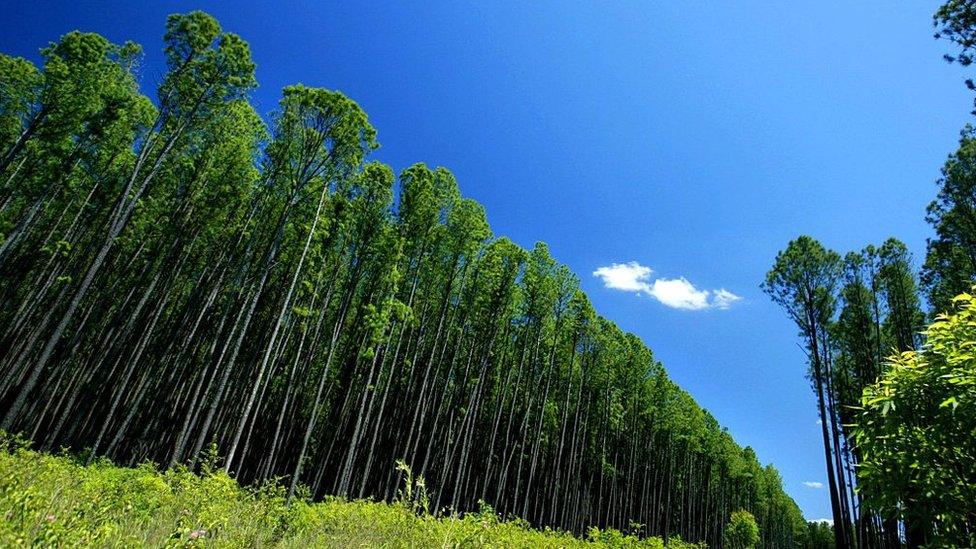

Shell aims to spend $100m per year on natural solutions to climate change, including forestry

On its own account, it aims to spend $100m per year on natural solutions, including forestry as a carbon sink, and less natural ones, including carbon capture and storage (50 million tonnes of it each year), and to go big on making hydrogen power work commercially for industry and heavy transport.

With such a big forecourts presence - 44,000 outlets in more than 75 countries - it intends to build that specialism from 6,000 plug-in points for cars in 14 countries to 50,000.

It made a small contribution towards that last month, buying Ubitricity, a German company with 2,700 charging points in the UK, or 13% of the total. Shell already had 1,000 at its forecourts.

Shell recently bought German company WiTricity, which has 2,700 charging points in the UK

But one striking aspect of this plan is that Shell is not following BP or Equinor into renewable energy stakes, at least on anything like the same scale.

It wants to double the amount of electricity it sells, having bought and rebranded First Utility three years ago, adding 450,000 Post Office broadband customers in the UK last month.

With expanding service station retail, adding collection points for online purchases, it's diversifying, but not focusing on renewable investment.

The vision has been set out on the same day a Shell-led joint venture has announced a subsidy-free wind farm in the Dutch North Sea. But it sees its strength as being a retailer and not a major generator of green electricity.

And wanting to be a good global citizen, it is aiming to get electricity to 100 million people who don't currently have it at home.

Tricky transition

This is a very tricky transition. Shareholders, both retail and institutional, are seeing oil majors less as a sure bet and questioning whether it's an ethical one.

The pressure is on all the oil majors - both to keep the dividends flowing and the share price up, and to set out a persuasive trajectory towards a greener future.

But if business isn't taking part in that transition, or is only pushed into it reluctantly by regulation, it's doubtful that climate change targets can succeed with them.

Related topics

- Published11 February 2021

- Published11 February 2021