How US nuclear missiles found a base in Scotland

- Published

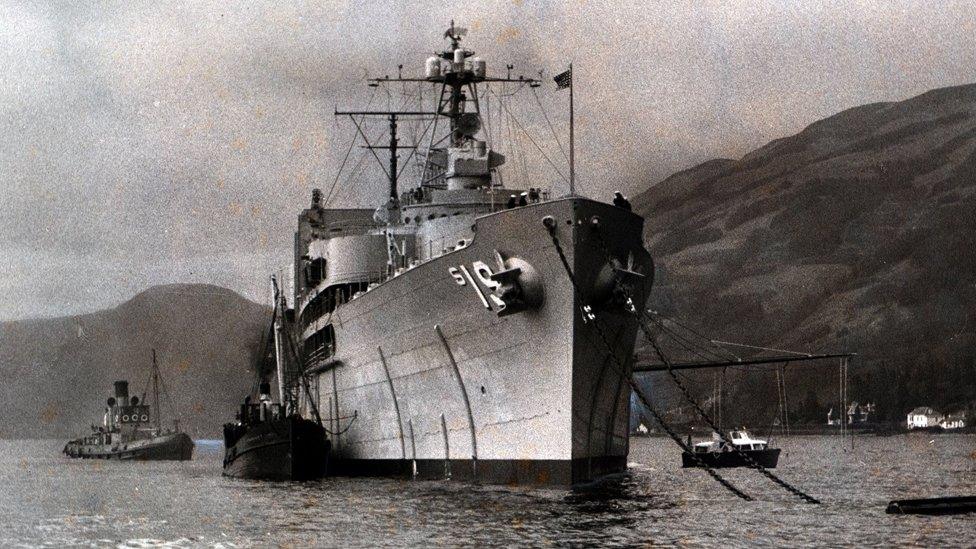

USS Proteus at anchor in the Holy Loch in 1961

Dunoon was no stranger to submarines and their crews by the time the first Americans arrived there in March 1961 but establishing a US base in Scotland was still a controversial move.

The Argyll town sits at the mouth of the Holy Loch on the east side of the Cowal peninsula. The loch opens straight out into the Clyde and a combination of deep waters, natural shelter, and easy access to the open sea, had already ensured it was a strategically important spot when war broke out in 1939.

The Royal Navy based submarines there throughout World War Two, carrying out operations across the Atlantic.

But the US base would be something completely different.

By the early 1960s both the USA and USSR were increasing the size of their nuclear arsenals.

The Americans developed the submarine-launched Polaris nuclear missile system but needed a base for their fleet in Europe.

The USA and Britain struck a deal which brought the missiles to the Clyde and over the course of the next decade the Americans would take over the Holy Loch while the Royal Navy built up its own base a few miles away at Faslane on the Gare Loch.

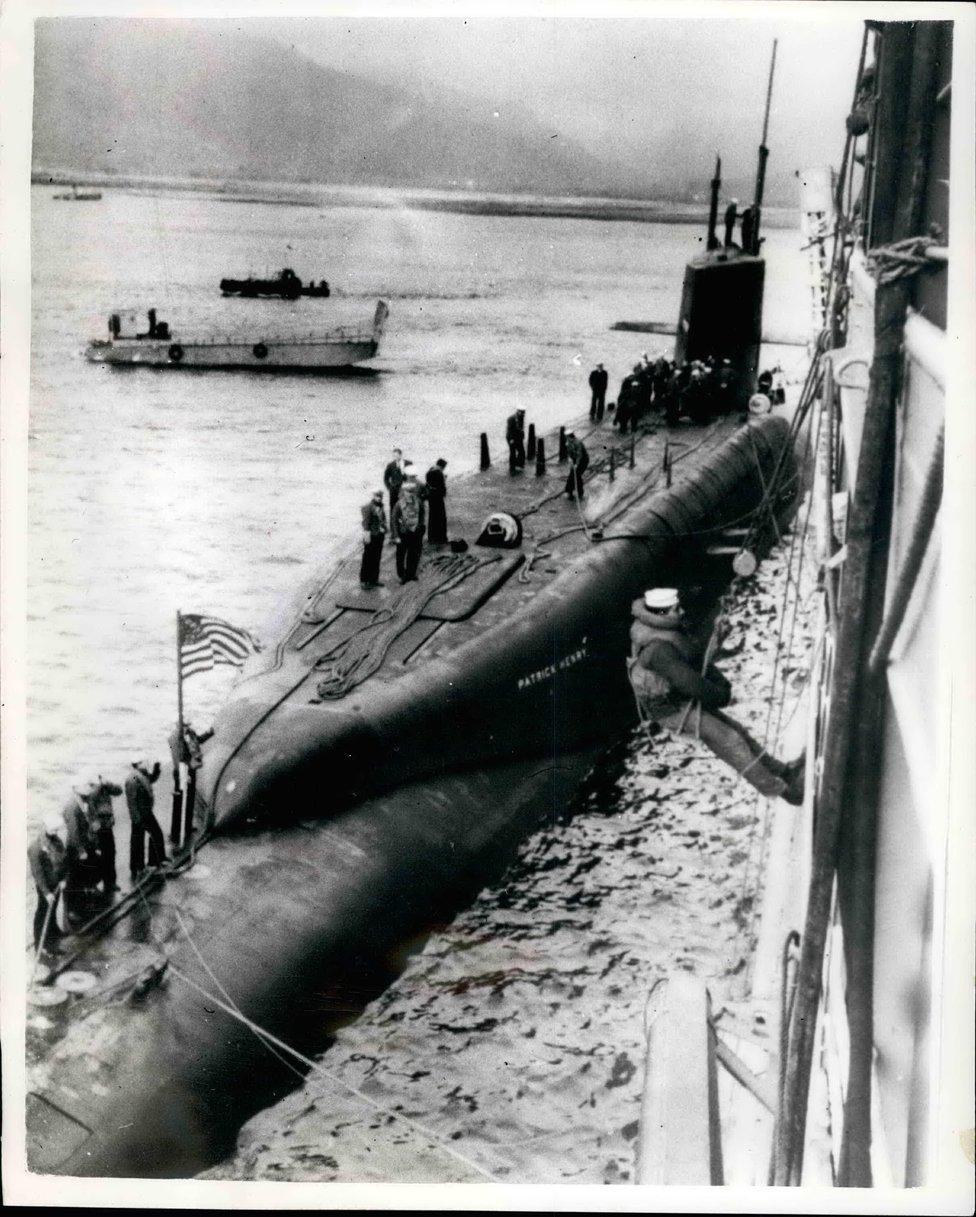

The American Polaris submarine 'Patrick Henry' arrived in the Holy Loch, and tied up alongside the depot ship 'Proteus'

On 3 March 1961, the submarine tender USS Proteus sailed up Holy Loch to establish the US base.

The giant ship, a veteran of the war in the Pacific, acted as a support vessel for the ballistic missile submarines, its crew dedicated to the maintenance of the underwater fleet.

The Proteus had a crew of 980 officers and men and up to 500 dependent families came with them. They would be based at the loch while the submarine crews flew in and out for tours of duty.

The US submarines brought the first Polaris missiles into British waters and from the start their presence was controversial.

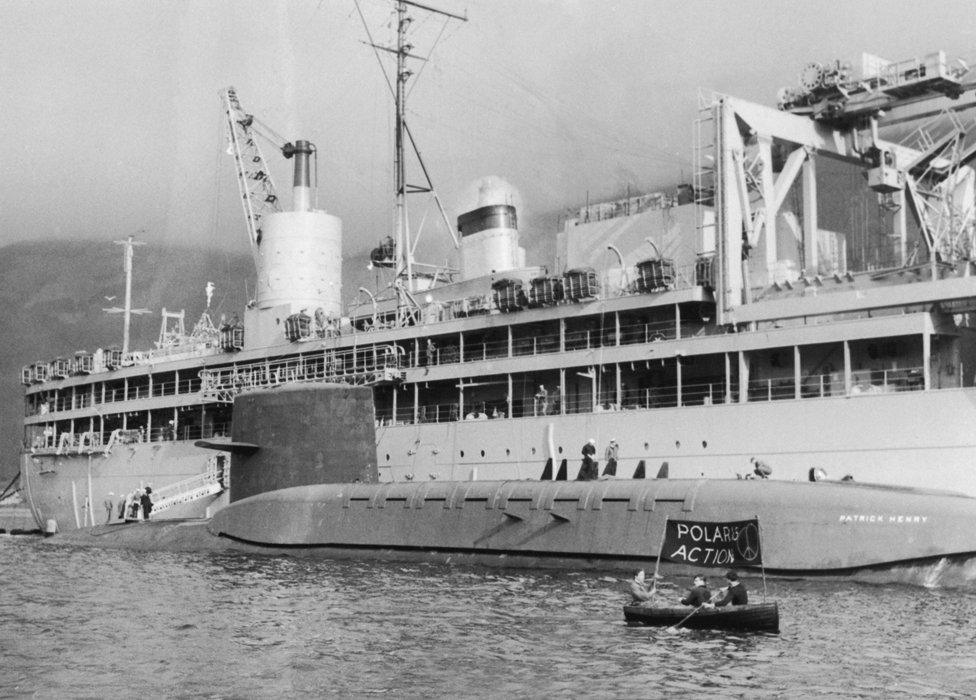

Anti-Polaris demonstrators carried out sustained protests at the US base

The day after the Proteus arrived, 1,000 protesters marched along the loch.

Isabel Lindsay was a founding member of Scottish Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (SCND) and one of those who protested.

She said: "The Holy Loch base brought a great surge of activity. An immediate coalition was formed with SCND, trade unions, sections of the Labour Party and of the churches, and it included the - at that time very small - SNP.

"This was a watershed moment both for the anti-nuclear movement in Scotland but, in retrospect, also for the broader political direction of change."

On the day the Polaris submarine arrived at Holy Loch protesters took to the water to demonstrate against it

Active and sustained protests, including marches and sit-ins, continued throughout the base's history.

The submarines brought the Holy Loch into the world of global politics but it also fundamentally changed Dunoon and its people.

By 1961, the town's glory days as a seaside resort were on the wane. The influx of hundreds of American sailors and their families was both a culture shock and a much-needed boost to the economy.

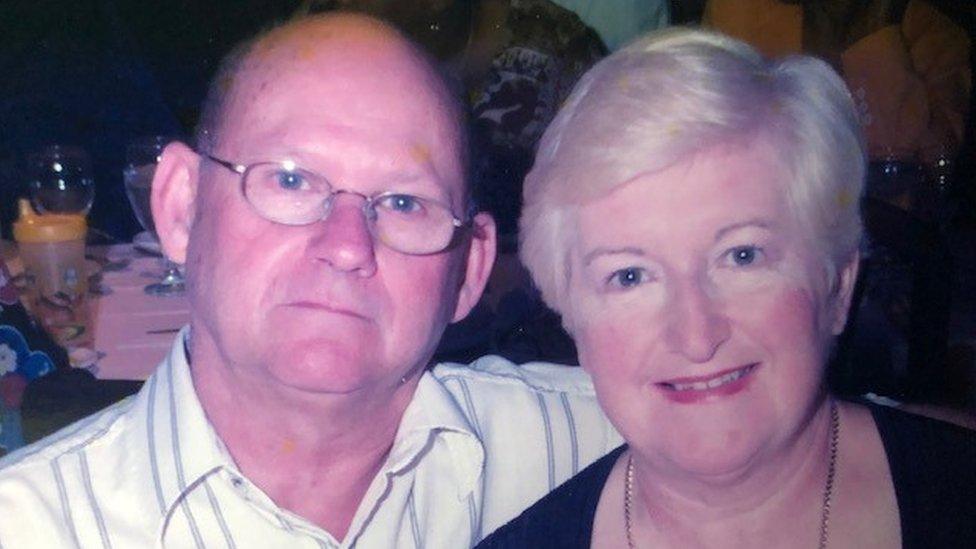

Gerry Pursley , from Kentucky, married local girl Linda Jones in 1963

Gerry and Linda returned to Dunoon and brought up four children there

Gerry Pursley was a 23-year-old from Kentucky when he came to the base in March 1962. Within three months he met 18-year-old local girl Linda Jones. They were married the following Valentine's Day.

"A lot of the guys met local ladies and got married," Gerry said. "People were getting married before I got here. Some were getting married in 1961."

In fact, between 1961 and 1971, a third of registered local marriages were between non-US women and US Navy personnel. These romances were accompanied by tensions between local men and the sailors.

Linda Pursley said: "There was some jealousy, you'd hear people say 'She's got herself a sailor' but most of the time there was no problem.

"The Americans warmed to Dunoon. A lot of them were from small towns and they felt at home here."

Gerry's naval posting took the Pursleys back to the USA for much of the 1960s but they returned to Dunoon in 1971, bringing up their four children there. Gerry worked as an engineer for the navy and then opened a repair business in the town.

"Gerry was always very popular because he was the only one who knew how to fix an American washing machine," Linda said.

Phil Ambagtsheer was originally stationed at Holy Loch in 1980 and now lives nearby

Another who stayed is Phil Ambagtsheer. Originally stationed at the Holy Loch in 1980, Phil immediately felt at home in Scotland.

"I'm from northern European extraction. I'm kind of gingery and I came from Los Angeles and my skin peeled all the time from the sun. When I got to the Holy Loch I acclimatised quickly."

Phil was a submariner, so flew in and out for tours of duty without living off the base.

"Over the years we came and went all the time but we managed to sample the town," he said. "A haggis supper from the chippy was a must-have experience. People used to dare one another to do it but I had one and never looked back.

"All that spicy oatmeal and all crispy on the outside. And the chips. I loved it."

An average of 3,500-4,000 Americans were attached to the Holy Loch at any one time but that did not always mean a lot of money went into the local community.

While many stayed in rented family homes or as lodgers in Dunoon, the majority stayed on the tender ship. The base also had its own services including a shop and bank.

Dunoon was said to have the biggest local taxi fleet in the UK and driving a cab was a good living, according to Phil Ambagtsheer.

"When I first came if you were travelling into Dunoon the ride cost about 85p and we would pull a fiver out. The driver would say it was too much but we would give them it anyway.

"They always ended us saying 'Suit yourself, mate'."

The end of the US presence at Holy Loch became inevitable with the end of the Cold War

The end of the US presence at Holy Loch became inevitable with the Cold War coming to a close. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the decision was taken to shut the base. The last ship left in March 1992.

Historian Trevor Royle wrote about the base in his book on the Cold War in Scotland, 'Facing The Bear'. He believes the Holy Loch was a vital part of Nato's defence strategy.

He said: "The base at Holy Loch was operational for 31 years and in that time its boats never fired a shot in anger. The Cold War peace held despite the constant threat of nuclear Armageddon.

"In 1992 very few local people were sorry to see them go, but the three decades of their presence left an indelible footprint. The submariners had forged links with the community which were both social and economic and long outlasted the 'American Years'."

Dozens of US navy veterans still live in the area. They meet to chart the history of the base online, and talk to local schools.

Gerry Pursley said: "I think it's a great part of the history of Dunoon. And I think really that you would find every sailor who served here enjoyed Scotland."

Phil Ambagtsheer, now 59, lives in nearby Inellan, overlooking the Clyde.

"The Scots people were generally just welcoming and gracious. You experienced that and you liked it and you returned it.

"I'm just lucky I got to come back".