Are Britain's bosses up to the job?

- Published

The shortcomings of British managers are being targeted in the Budget and also by a senior adviser to the Scottish government.

There is a push to get them learning about business skills they lack, and to understand better how to use technology.

Brexit has lowered expectations of the boost to productivity from inward investment, so there's a need for home-grown business to learn for itself.

British workers used to get the blame for the nation's economic woes. Less so now. The finger of suspicion is at least as likely to be pointed at the British workers' bosses.

Do they have the skills necessary to manage people, and to get the most out of motivated workers?

Are they able not only to invest but to know how to get the best out of that equipment, market insight or acquired subsidiary?

Over the course of a career, are they keeping their skills up to date?

Or are they the prime suspects in the woeful lack of productivity growth that has long beset the UK and Scottish economies?

Managing their way through the current crisis is proving, for many, to be the toughest task they have ever undertaken.

Navigating the more difficult terrain when government support is withdrawn, and when creditors come calling, looks likely to be tougher still - moreso if demand fails to pick up pace.

Business class

So they're getting some help from both the Treasury and from the Scottish government's independent economic adviser.

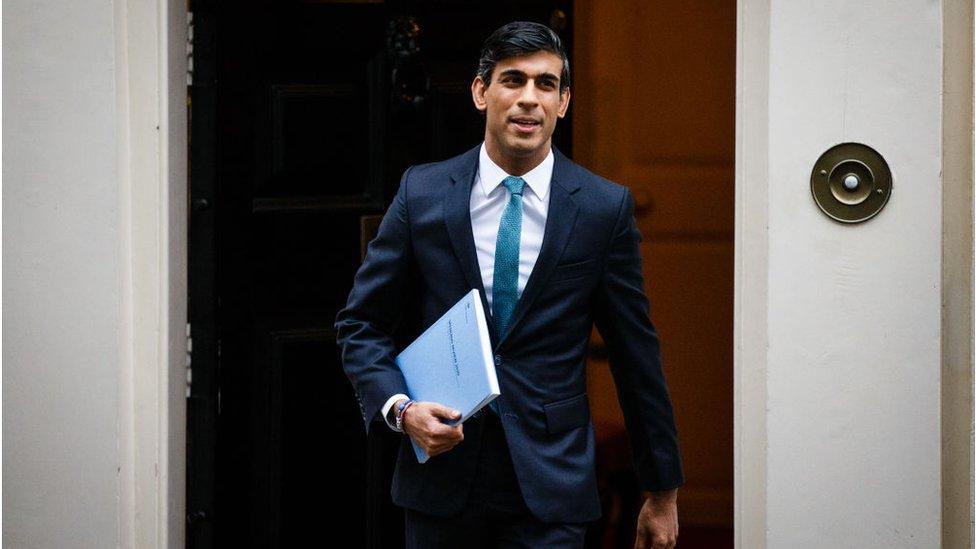

Rishi Sunak's Budget on Wednesday is about crisis now and recovery soon, with a message for the longer-term about the reckoning to follow.

For the second, recovery part of that, he has found more than £500m to spend on "Help to Grow" - UK-wide initiatives both to help businesses embrace digital technologies, and to send bosses back to school.

The technology is to be delivered in vouchers, with 50% off software that firms might find useful. Customer relationship management (CRM) software for instance, is said to boost turnover per employee by 18% over only three years. That's if it is adequately understood and deployed.

As for going back to school, many bosses think business class is only for air travellers. Unlike many other countries, learning the right skill-set for managing has not been necessary for climbing the British career ladder.

So up to 130,000 small and medium-scale enterprises (SMEs) are to get subsidised access to university level training. They are to get 50 hours of tuition and one-to-one business mentoring.

Of course, there's timidity about a Conservative Chancellor criticising Britain's bosses.

Mr Sunak enthuses: "Our brilliant SMEs are the backbone of our economy, creating jobs and generating prosperity - so it's vital they can access the tools they need to succeed".

But the Treasury goes on to point out that the UK is rated fifth out of the seven G7 industrialised nations for "the use of management practices". In trying to tackle poor productivity, it's perhaps surprising that league table hasn't got more attention.

Step up, lean in

The issue has also been addressed, just north of the Cheviots near Jedburgh, where Mr Benny Higgins has been considering the challenges of the economic recovery in Scotland.

The former chief executive of Tesco Bank made an unusual career twist into land ownership, appointed by the Duke of Buccleuch to chair the aristo's family firm, controlling a very large landholding and investment portfolio.

Mr Higgins was commissioned by Scottish ministers last year to produce a post-Covid recovery blueprint.

One of the recommendations about which he felt particularly strongly was the need for banks to step up, or to lean in - to take a proactive role in helping their business clients survive rather than merely controlling the credit lever which dictates whether firms are pitched into the pit of administration or allowed to fight back to financial health.

To get them doing so, he wants governments to use their power to summon economic players to the table, most prominently bankers, and to get them to take on more of the burden of making recovery stick.

Benny Higgins was sent back to work, to talk to bankers and others about making this happen. His latest report, external was published on Monday, and runs to 35 pages.

It is blunt about the need for Scottish ministers to open up more effective channels into business.

It is also clear about the need for banks to show patience, forbearance and innovation in helping customers get from crisis to sustained recovery. There's a reminder that they did badly after the financial crash at ensuring proper redress systems for customers who were unfairly treated, so that should not be allowed to happen again.

Nor does the report pull its punches about the abilities of small company bosses.

"There is strong evidence," writes Mr Higgins, "that many of the challenges facing the Scottish economy are rooted in the limited management and strategic capacity in our already stretched SME base.

"In many industries these challenges will be exacerbated by a potentially permanent shift to home working, posing new challenges for the development and integration of innovative, high performance operating models.

"In some ways, this challenge is ironic since several of our universities operate management schools of international distinction. In this time of unprecedented challenge, this is a national asset that must be deployed for greater impact on the economy. These issues have previously been highlighted by the Enterprise and Skills Board; but an effective solution which operates at scale does not appear to be in place."

'Passive and patchy'

The report concedes that some firms, notably in retail and hospitality, have very small management teams, and are stretched thin at the best of times. But even in applying for funds, they lack the basics.

"There is anecdotal evidence that applications for both public and private sector support packages routinely demonstrate a basic lack of expertise in accounting, forecasting and business planning," reports the former Tesco Bank chief.

So there's a call for better skills and better advice, from banks and from enterprise agencies. However: "While I recognise that a great deal of this already exists across the public and private sectors, the feedback from businesses is that it can be passive, patchy, confusing to navigate, too generic to be useful and often misses critical topics where more intensive, personalised support and expertise is required.

"Small retailers flagged the example of being frequently advised to invest in e-commerce but with little guidance about the most effective platforms for their market, nor where to access credible products or expert consultancy."

Technology can be key, but how it is deployed is as important. Broadband is not as much a problem as limited use of its potential: the report cites evidence that only 7% of Scottish companies maximise use of technology, while 76% don't use it at all or only use it at a basic level.

With similar broadband potential and access to the same kit, Scotland lags a long way behind EU countries such as Denmark in its use of technology.

These are changed times. Artificial intelligence is accelerating the job-replacing potential of technology.

And by leaving the European single market, Britain appears to have made it less attractive to multi-national firms to bring their new ideas and superior productivity into the country, with a well-recognised influence on neighbouring local firms and suppliers.

So coming out of crisis and heading for recovery, there are multiple challenges for bosses. And there is the question: are Britain's bosses up to the job? Do their workers have the managers they deserve and need?

Related topics

- Published2 March 2021

- Published2 March 2021

- Published2 March 2021