The man who captured a fading industrial Scotland

- Published

The Clydesdale Tube Works in Bellshill pictured in 1975

For John Hume, it started with a boyhood fascination of watching newly-built battleships voyage down the Clyde which led to a collection of more than 25,000 photographs of Scotland's fading industrial heritage.

His aim was simple - to create an exhaustive record of the factories, shipyards, mills and steelworks which were all facing the wrecking ball.

The 83-year-old would later turn his passion professional, playing key roles in preservation bodies.

But Mr Hume told BBC Scotland his attitude to preserving the country's industrial heritage is the same now as it was in the 1960s.

"It comes back to affection," he said. "If we could preserve the people that we knew when we loved them - mothers, fathers, uncles, aunts, friends - we would love to do that.

"We would have a library of people that we would go and see. Well that's the same with buildings, and machines, and books and you name it.

"You know that if you can express that feeling for something by preserving it, then people can come to see it in the future and see what you loved, and see what they can love in it."

Crowds gather at Bowling near Glasgow in 1968 to watch the Queen Elizabeth II (QE2) sail down the Clyde for her trials

The Lord Farringdon steam engine at the Balornock Motive Power Depot in Glasgow in 1966. The city's now demolished Red Road flats are being constructed in the background

Mr Hume started taking pictures of under-threat industrial sites in the 1960s and carried on until the 1980s with the collection of more than 25,000 photographs now held by Historic Environment Scotland (HES).

It was in that early period where his cataloguing work, especially around his native Glasgow, felt most critical, he said.

'Last chance to document this way of life'

The industrial-era buildings in Scotland's largest city faced a number of threats, not least their own commercial decline but also the huge swathes of land needed for the M8 motorway.

He said: "In the 1960s there was a palpable sense that things were changing, the old ways were dying out.

"I realise now, but not at the time, that the reason I got into many places was because the directors or managers knew what was coming - that this was the last chance to document this way of life."

The Houldsworth's Cotton Mill on Cheapside Street in Glasgow in 1969. On the right of the picture is an approach road for the new Kingston Bridge

A horse and cart lines up with a lorry outside the Fruitmarket in Glasgow in 1965

As a junior university lecturer in the 1960s, Mr Hume was part of a small band of people battling to get industrial archaeology to be treated equally with more traditional fields.

He said: "It is hard to think of it now but nobody wanted to know back then, it was a real struggle.

"I just wanted our industrial heritage to be on the same footing and have the same respect as a medieval cathedral, because they have both contributed valuably to our world."

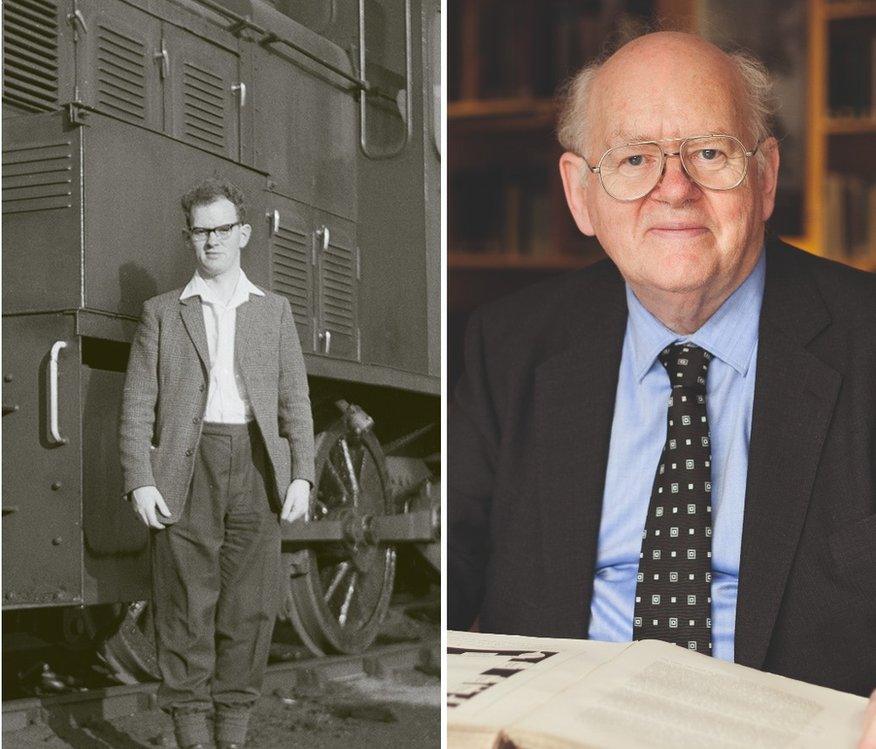

Mr Hume pictured on the left in the 1960s and on the right in 2015 at the headquarters of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland in his final year as its chairman

Mr Hume's passion for preservation went from the voluntary to professional and he undertook a number of key roles in the preservation world in his working life, notably as Scotland's Chief Inspector of Historic Buildings and then chairman of the now defunct Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

They were roles where Mr Hume's impact on protecting the country's industrial heritage is still felt today.

Buildings given listed status where Mr Hume played a role include the giant cranes of Clydebank and Finnieston in Glasgow, the White Cart Bridge in Renfrew, Central and Waverley railway stations and Queensberry House, now an integral part of the Scottish Parliament.

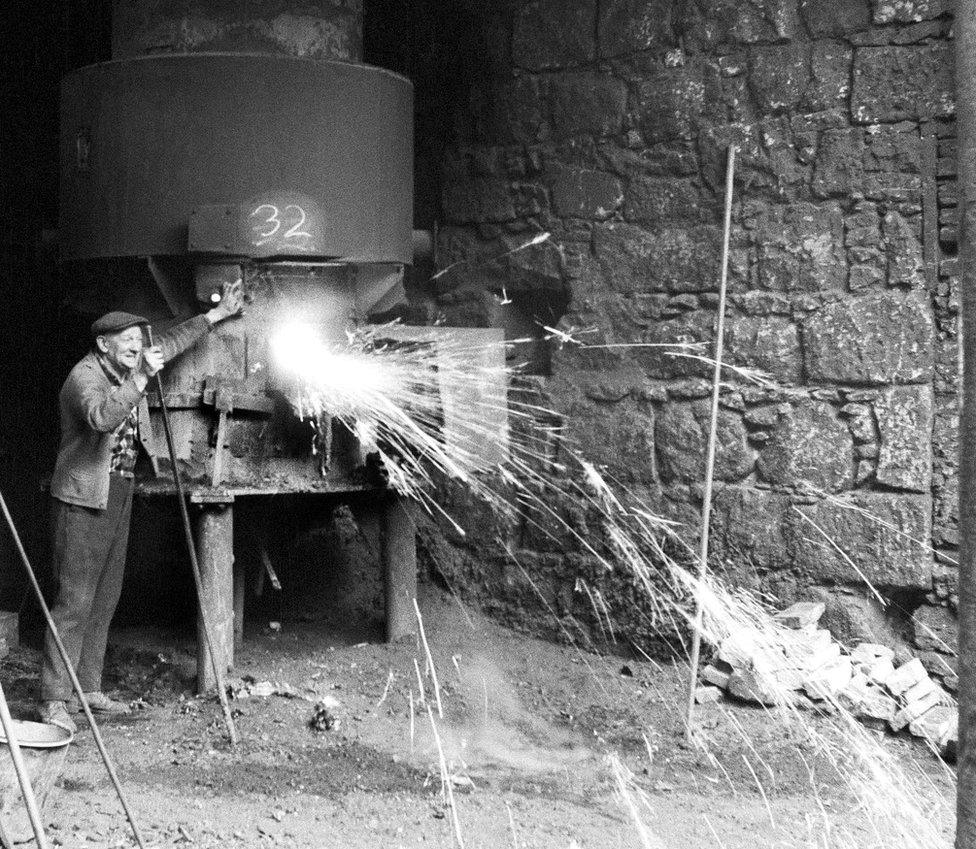

An ironworker rests on a cupola furnace at the Barry, Henry and Cook foundry in Aberdeen in 1971

Glasgow's Renfrew Ferry at Yoker Terminal in 1967. Mr Hume said of this picture, "These are the lucky moments. Where everything comes together to tell a story."

Asked if there were as many modern industrial buildings that deserved documenting for future generations to enjoy as where in his collection, Mr Hume said it was "unlikely".

The retired academic added: "If you look at the buildings built after 1950, very few are that good or indeed last that long and I think part of the issue is we are losing sight of the fact that buildings are not about bricks or steel, they should be about people.

"We seem to have have lost the concept that buildings should make us feel better."