Covid-19 in Scotland: Why are confirmed cases flatlining?

- Published

- comments

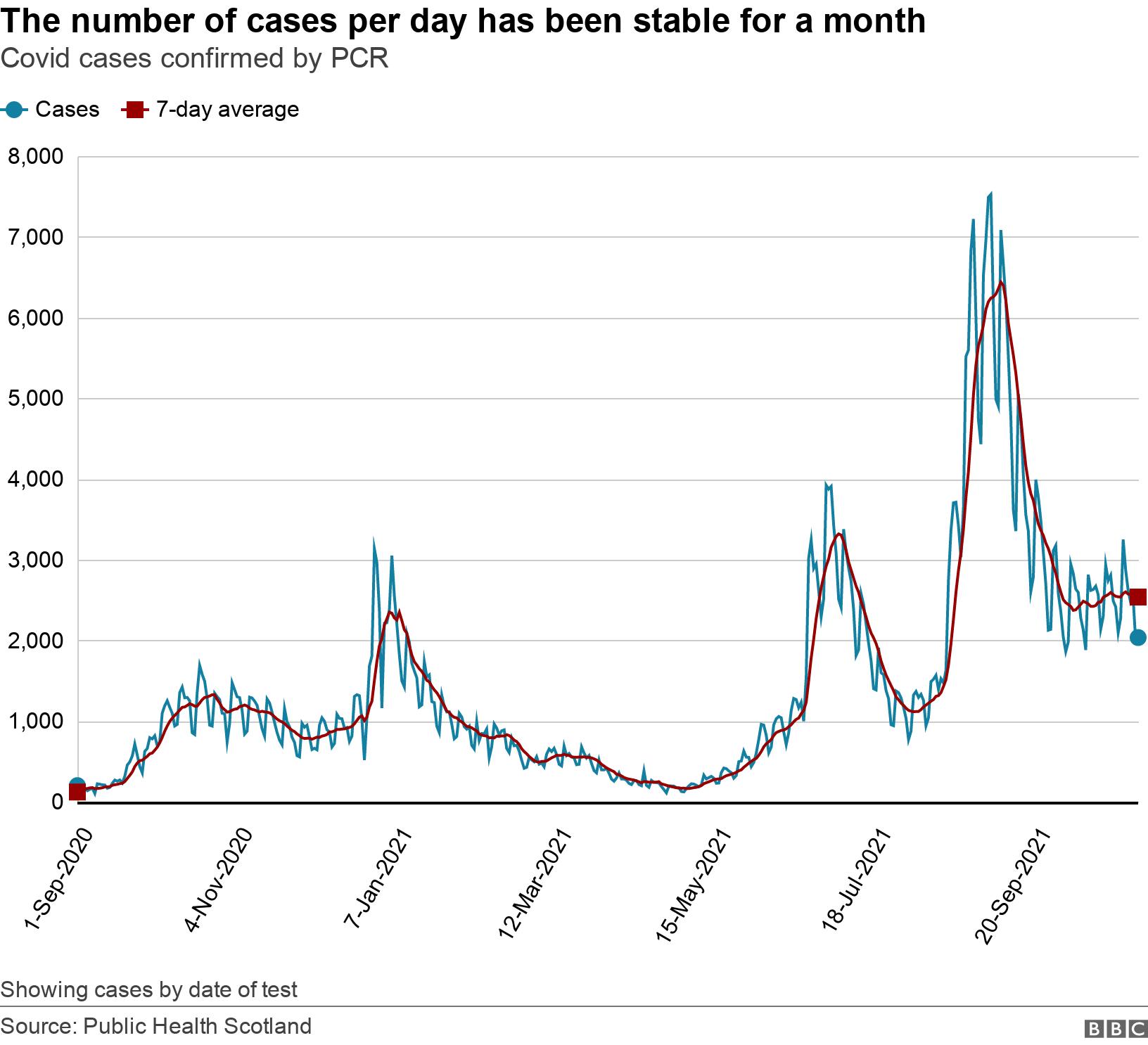

For the last month, Covid infection levels in Scotland have been doing something unusual.

Since the beginning of October cases haven't going up or down significantly, but have just hovered around 2,500 a day. It's the first time this has happened, so what's going on?

Throughout Scotland's pandemic, the number of daily Covid cases has mainly been in motion, whether that's been going up or coming down.

But over the last month, infection levels have barely moved, according to Public Health Scotland (PHS) data.

A chart showing cases since the arrival of the "second wave" - when mass testing had been firmly established - illustrates how uncommon this is.

Paul Hunter, a professor in medicine at the University of East Anglia, external, says there's a basic pattern of ebb and flow which infectious diseases tend to follow.

"In an epidemic disease, the disease appears, it spreads rapidly but at some point fairly soon it starts running out of people to infect and therefore it peaks and starts disappearing," he explains.

"Ultimately it may actually go away - although in today's world that's not so common."

Peaks and troughs

Prof Hunter, an infectious disease expert, says it's likely Covid-19 will become endemic in Scotland - the point where a disease maintains a constant baseline level within a community.

"Endemic infections are infections that are with us forever, although that doesn't mean to say you don't get peaks and troughs," he says.

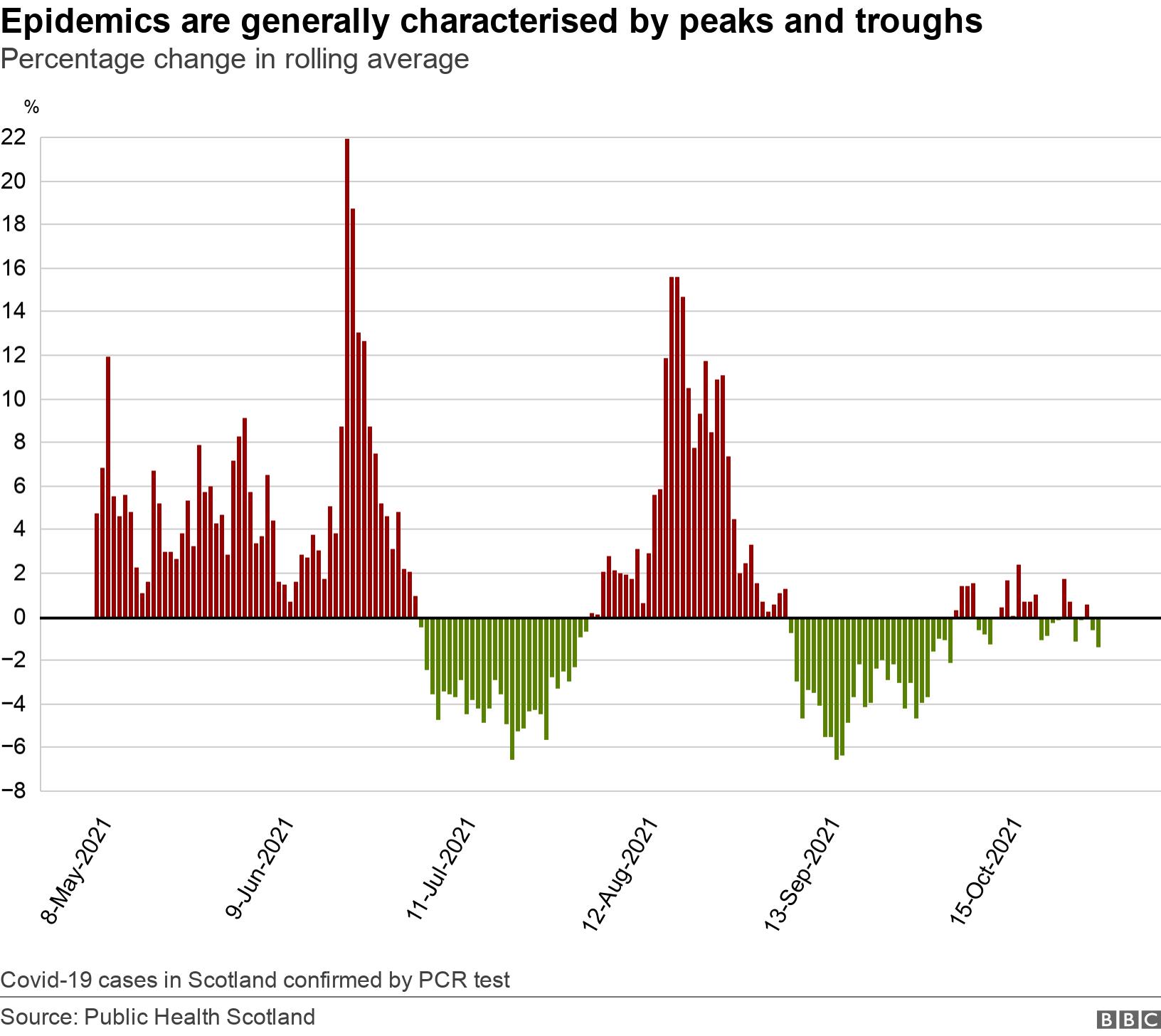

Another way of looking at how Covid-19 is ebbing and flowing in Scotland is by tracking the change in the seven-day average of daily cases.

If cases are moving sharply up or down then the average may be increasing or decreasing by 10-15% each day.

Smaller changes mean stability, especially when the figure is flipping between positive and negative.

Prof Hunter says the recent period of flatness in Scotland, especially at a reasonably high level of cases, has not been seen much in the UK and could be a sign of things to come.

"It is a bit unusual and maybe it's an indication we're getting to the equilibrium point in Scotland," he says.

"I say maybe - in five years' time we can look back and say we were at the equilibrium or not. You can't really say it while it's happening."

An "equilibrium" would be the level of infection we could commonly expect as Covid becomes endemic in Scotland.

Disease 'oscillations'

There's a lot of complex maths, external behind how infectious diseases evolve from epidemic to endemic over time.

Scientists need to take into account of changing levels of immunity, the length of time people are infectious and a disease's ability to spread.

On top of that, populations are in constant motion. Every time someone dies from an infection or a baby is born, the equation changes.

"When a disease shifts from being epidemic to endemic you get these oscillations. The other thing is that these waves dampen with each oscillation so it's less intense as it approaches the endemic equilibrium," Prof Hunter says.

"But you rarely see that as clearly in the real world because in the real world you've got the seasonality - that continues to cause oscillations forever."

People tend to spend more time mixing indoors over the winter

Prof Hunter believes Covid-19 will settle in to a pattern of seasonality like the flu, with peaks in winter and troughs in summer.

This is because the chance of being infected over the winter is higher as people spend more time indoors. Once you've recovered from an infection you'll be immune for a while, but that immunity is beginning to wane as winter approaches again.

"Immunity comes and goes and transmission potential comes and goes - and the two reinforce each other," says Prof Hunter.

Perhaps the last month is a signal Covid is approaching an equilibrium, but the professor also thinks there is another avenue worth exploring.

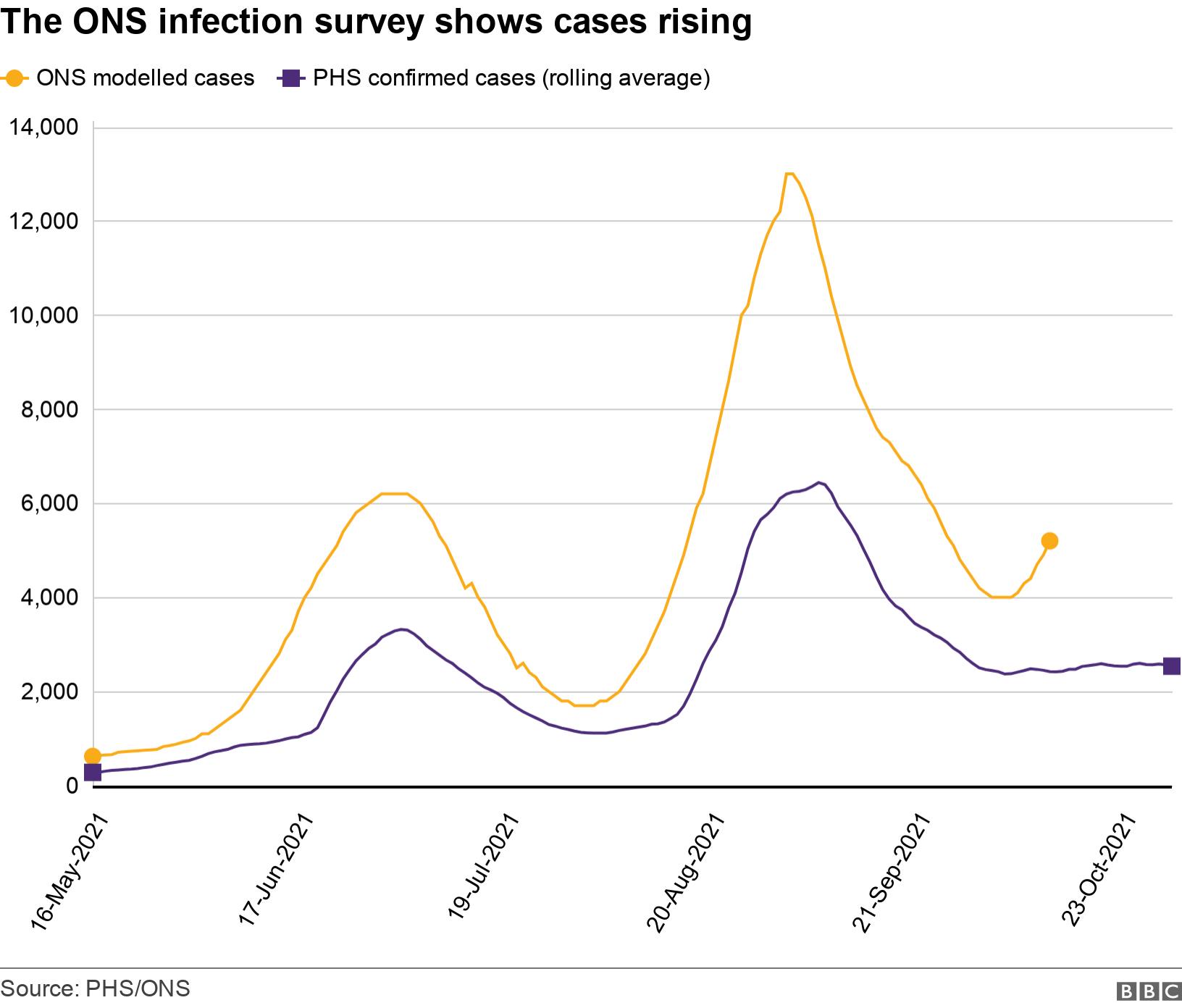

There's a chance cases aren't flat at all - infections might actually be rising, but going undetected or unreported.

Using the Office of National Statistic (ONS) Covid infection survey, external, which tests a random selection of people, it's possible to get another view of case levels in Scotland.

This does indeed show a different picture.

The ONS estimate is currently higher than confirmed cases - as it always is - but it also shows a distinctive curve upwards at the start of October, rather than the flat line of confirmed cases.

Prof Hunter says this could indicate a rising number of asymptomatic cases going undetected, but he also notes that the latest ONS figures only go up to 12 October and the most recent data in this survey is always subject to revision.

The question here is "What is an acceptable level of Covid cases?"

The NHS is under severe pressure and some doctors warn that already patients are suffering or dying unnecessarily.

A&E is seeing record waits. Thousands of people can't get the operations they need and will become sicker as delays go on. Shortages in social care mean people can't get out of hospital to get the care they need at home.

Every health board is working at capacity.

Covid has a significant role to play in that. There are still more than 900 people in hospital with Covid, and that means staff looking after them instead of others.

High community transmission means NHS workers get sick too, so fewer nurses and doctors with even more patients and ever longer waits.

All of this before it gets colder with cases expected to go up and other infections like flu come along.

There are of course other consequences if restrictions were to be re-introduced to bring down cases and politicians have to balance those harms against those that Covid causes.

But as one critical care doctor put it on Twitter, external: "It won't be like a disaster movie. We'll just see more people suffering more, and dying a little more often, in preventable ways."

Are we endemic yet?

In short, probably not.

While we may have seen a glimpse of what endemic looks like given current social measures and levels of immunity - both from vaccination and infection - there's a way to go yet.

Epidemics tend to be modelled in years and decades rather than months.

Prof Hunter warns this winter is likely to be difficult with cases rising and more pressure on the NHS, but he does believes the "disease burden" will lessen over time.

"Although the virus is here to stay forever, the disease isn't," he says.

"You're going to get it every few years forever probably, but the severity of the subsequent infections are always less than the earlier ones, on average."

It's a view echoed by the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine creator, Prof Dame Sarah Gilbert, who recently told a Royal Society of Medicine webinar that Covid-19 would become like the common cold.

"It's not going to be over this winter, but this time next year we'll certainly be seeing a lot less severe disease," Prof Hunter says.