Covid in Scotland: What's behind the latest surge?

- Published

- comments

The restrictions introduced to slow down Covid will be with us a little longer

Just a few weeks ago it seemed Covid was at last losing its grip on our lives.

Under the Scottish government's strategic framework for managing Covid, , external Monday 21 March was meant to be the date when the last legal restrictions would be lifted.

Now, against a backdrop of surging cases, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has announced that face coverings will be required in shops and on public transport until early April. So what's changed and why?

With the world's attention focused on the war in Ukraine, it's unsurprising that a recent resurgence of infections has not attracted the coverage it might have done earlier in the pandemic.

The previous big Covid surge came in late December and early January when the faster spreading Omicron variant prompted a raft of new restrictions including strict attendance limits on large events, the closure of nightclubs and the return of social distancing in pubs and restaurants.

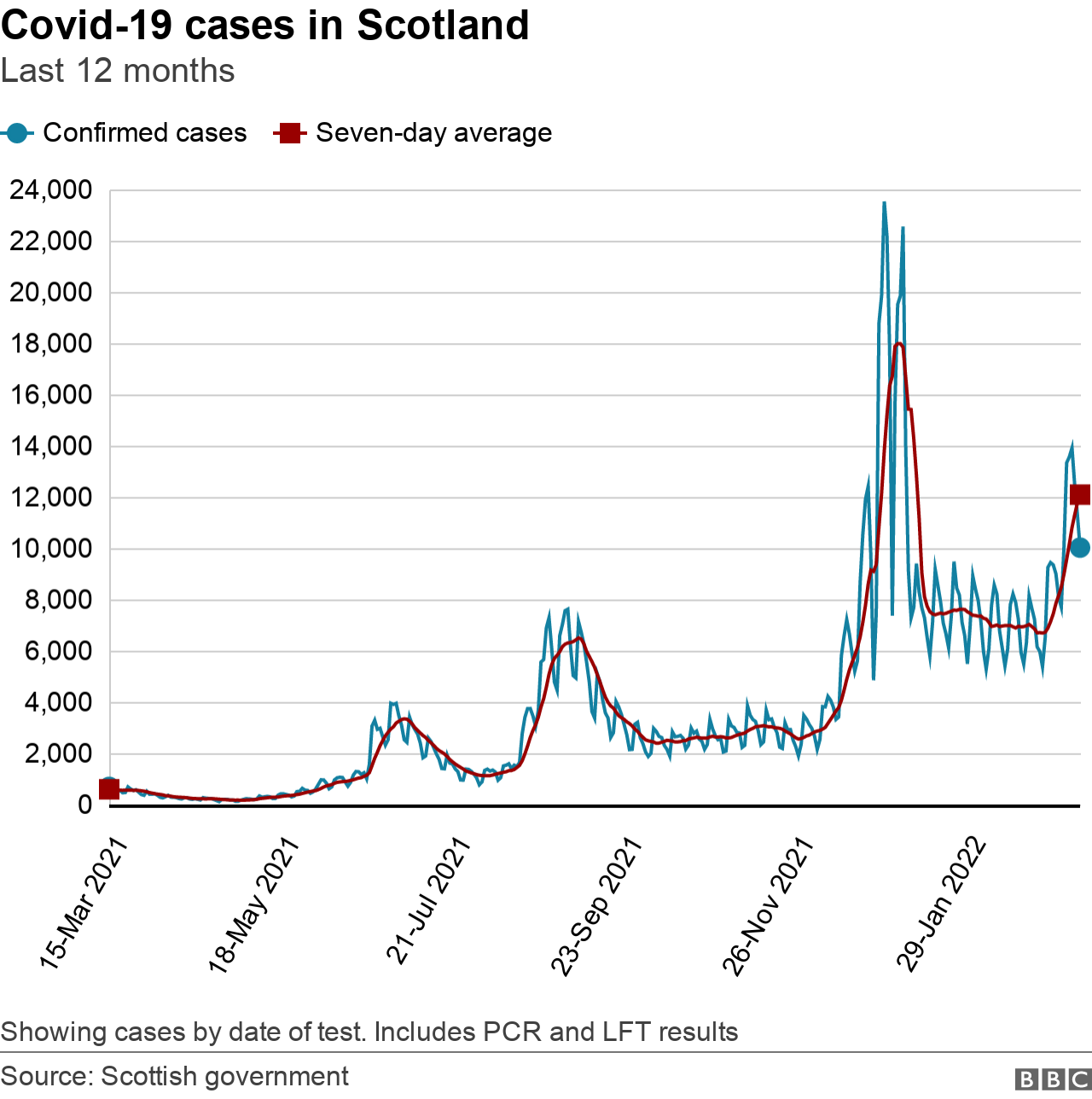

Daily case numbers peaked at more than 20,000 on 3 January, then fell away rapidly before levelling off.

By late February we were typically seeing about 5,500 new confirmed infections per day - but that changed at the start of March.

Some of the increase may be explained by a change in the way the figures are presented, as re-infections are included in the numbers - but it now seems clear that something else has been happening.

While the daily case figures have in the past been a reasonable guide to infections, the shifting emphasis onto lateral flow tests rather than PCR testing has led to a suspicion that many positive lateral flow results are not being reported.

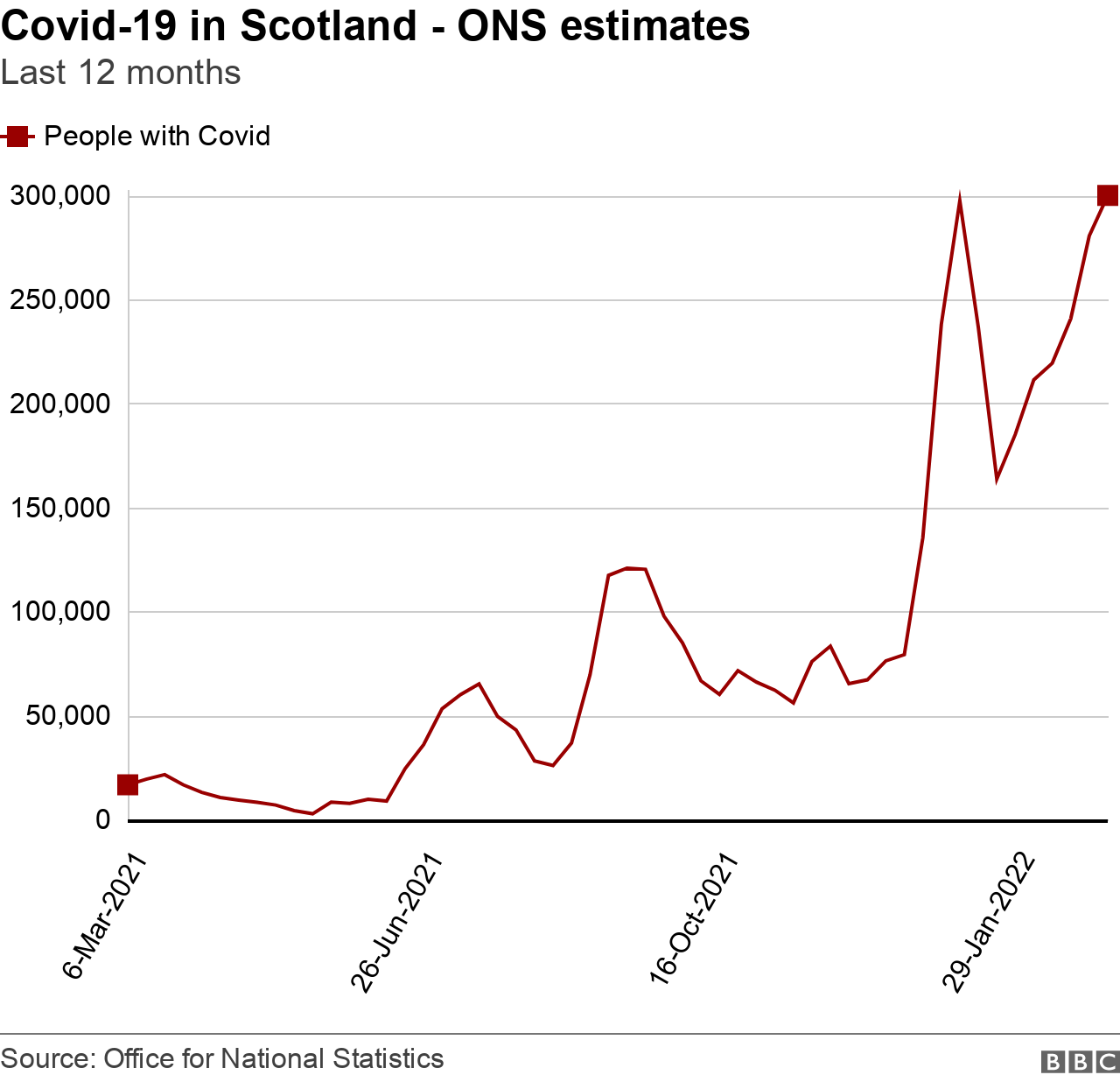

Public health experts are increasingly focusing instead on the weekly Office for National Statistics (ONS) survey - where swabs are collected from thousands of households across the UK to give a snapshot of how the virus is circulating.

Importantly, this survey picks up infections among people who are showing no symptoms, who would not show up in the daily figures.

The following chart shows how many people in Scotland are estimated to have had Covid each week, based on the ONS sampling.

For much of the time, these ONS estimates mirror the daily cases data, but if you look closely there are some key differences.

The ONS figures suggest that while Covid numbers did fall back sharply after the early January Omicron peak, this respite only lasted for about a fortnight before infections started climbing again.

They also suggest that in recent weeks, the daily case figures have drastically underestimated the extent of Covid infection.

The most recent estimate, for the week to 6 March, is that 5.7% (one in 18) of Scotland's population had Covid, the equivalent of 299,900 people - which is the highest figure since ONS sampling began in autumn 2020.

So what's behind the increase?

BA.2 - the 'stealth' version of Omicron

Covid-19 has developed numerous variants and sub-variants

The Omicron variant of Covid-19 was first identified in South Africa on 24 November, and was detected in the UK a few days later.

Fears about its increased transmissibility proved well-founded as it replaced Delta as the dominant strain, but for most people it caused less severe illness - which contributed to a fall in mortality. Vaccination and improved medical treatments have also driven down the death rate.

Omicron is an umbrella term for a number of closely-related versions of the virus - not so different that they are classed as new variants but instead regarded as "sub-variants."

The original version of Omicron is known as BA.1 but early this year a number of countries reported a rise in cases involving the BA.2 sub-variant.

Sometimes dubbed the "stealth variant", for most people BA.2 Omicron also causes a milder version of the disease than Delta, but it appears to spread even faster. According to Danish scientists it could be 1.5 times as transmissible as BA.1.

BA.2 is now the dominant strain in Scotland - accounting for 85% of cases - and it's come at a time when many of the earlier restrictions such as vaccine passports and limits on large gatherings have already ended.

It's also likely that we're seeing waning immunity over time as the protection given by vaccines wears off. For some older people, it was last autumn when they had their third jab.

Even having had Covid is no guarantee you won't get it again - about 10% of new cases are re-infections, according to Public Health Scotland.

A spring booster programme is now under way for the most vulnerable including the oldest age groups, to top up their protection with a fourth vaccine dose.

What impact is it having?

The better news is that, so far, there doesn't appear a sharp upturn in death rates or numbers of people who are so ill that they require intensive care treatment.

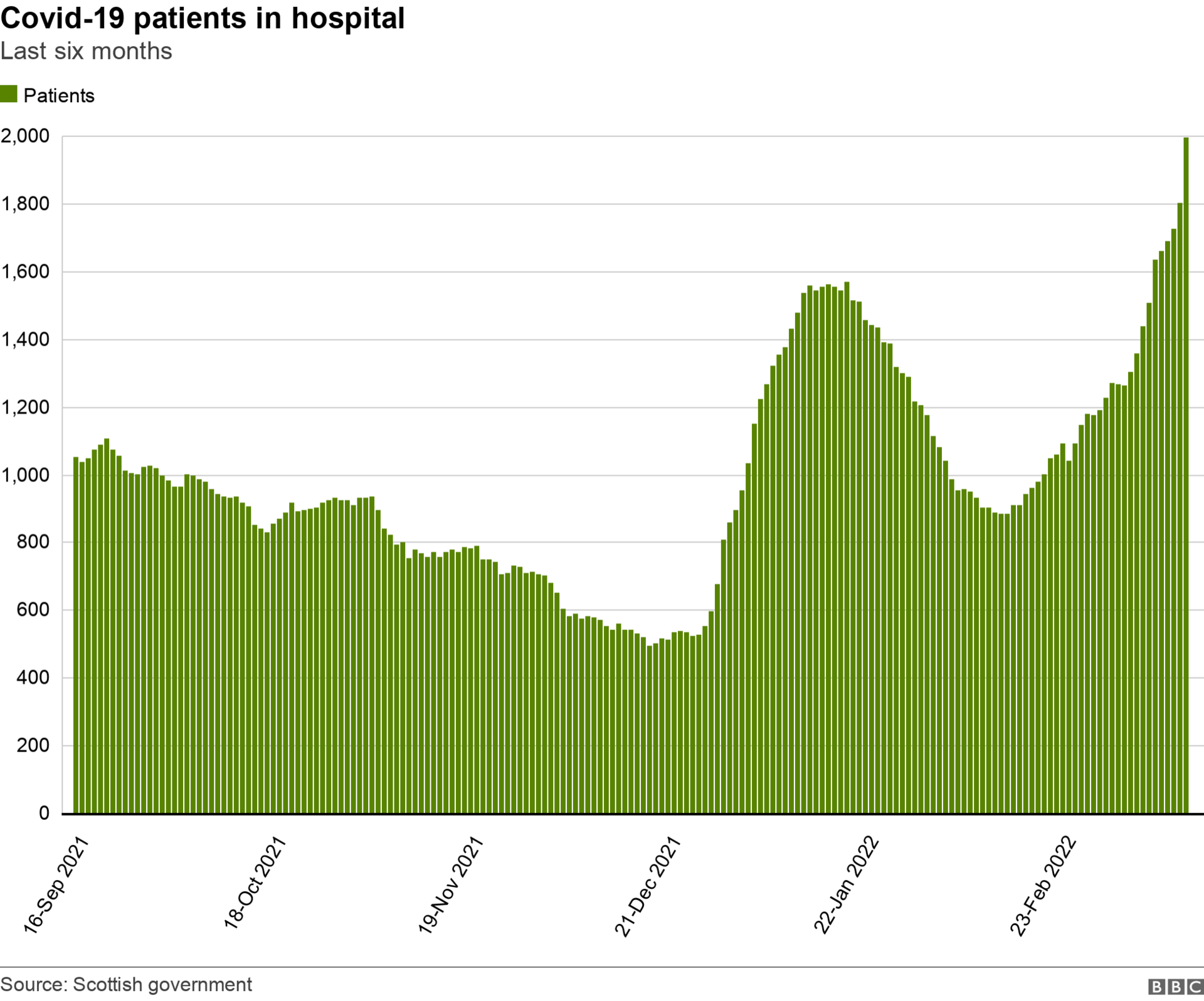

There has, however, been a steady rise since mid-February in the number of patients in hospital with Covid.

On Tuesday there were 1,996 Covid-positive patients, higher than the January 2022 Omicron peak and not far short of the whole-pandemic peak of 2,053 patients seen in January 2021.

The chief medical officer, Prof Sir Gregor Smith, says hospital occupancy is particularly increasing for the over-60s, partly because of their increased vulnerability but also because older people tend to have longer hospital stays.

Not all of these patients will be in hospital because of Covid - many will have come in for other ailments, but then tested positive.

But regardless of how ill these patients are, such big numbers inevitably put enormous strain on the NHS.

NHS Lothian and NHS Grampian say they have more Covid patients now than at any time in the pandemic.

NHS Lanarkshire has said its three acute hospitals are operating beyond capacity and is warning of knock-on impacts on A&E waiting times.

Greater Glasgow's health board says its hospitals are also near capacity, while NHS Highland says some elective surgery is having to be cancelled.

Will mask wearing make a difference?

Some might argue that there's little evidence that mask wearing will slow down transmission given that case numbers are already soaring even with existing restrictions in place.

Scottish Conservative leader Douglas Ross argued in Holyrood that the public should be trusted to take the steps they think are right to protect themselves.

Leading NHS Grampian health expert Jillian Evans, however, had argued that retaining face coverings a little longer would send an important signal.

She told the Press and Journal newspaper, external: "Our behaviour is influenced when we see things - such as masks. They are a reminder that we need to be more cautious."

Prof Sir Gregor Smith had also advocated a cautious approach.

The phrase "living with Covid" is increasingly heard on the lips of politicians and health experts, as we move from a pandemic phase to endemic - where the disease is always with us, possibly with seasonal peaks like with flu, but with measures in place to protect the most vulnerable.

Nicola Sturgeon says the face masks rules should only be with us a little longer, but even when the legal requirement is dropped, the guidance may still advocate their use.

With spring and summer approaching, the hope will be that pressures on the NHS will ease in the coming weeks, but in the meantime people will be urged to maintain voluntarily many of the safeguards that have previously been backed up by law.

Related topics

- Published14 March 2022

- Published10 March 2022

- Published15 March 2022