Could Scotland legalise assisted dying?

- Published

The euthanasia debate is returning to Scotland, as a final proposal for an assisted dying bill is lodged at the Scottish Parliament.

Liberal Democrat MSP Liam McArthur aims to introduce the right to assisted death for mentally competent adults with terminal illness.

Previous attempts to change legislation in Scotland failed.

Opponents have criticised the bill, calling for more support for living and improved palliative care.

A report on the 14,038 responses to a consultation, external on the Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) bill has also been published.

The submissions included first-hand accounts of living with, and caring for, someone with a terminal illness who had experienced great pain and suffered a "bad death".

About three quarters of respondents supported the proposals for assisted dying for terminally ill adults.

A previous attempt to change the law was originally brought forward by the late independent MSP Margo MacDonald, who died in 2014 after a long battle with Parkinson's disease.

The bill, which would have allowed those with terminal illnesses to seek the help of a doctor to end their own life, was rejected in 2015 by 82 votes to 36 following a debate at Holyrood.

Mr McArthur, MSP for Orkney, told BBC Radio's Good Morning Scotland programme he was hopeful that his members bill would receive cross-party support and lead to a change in the law next year.

"We've had two elections [since the last euthanasia bill] so the membership of the parliament is very different," Mr McArthur said. "It's only about a third of the MSPs that were present back in 2015 who are still present now and who had an opportunity to debate and vote on the issue last time round.

"In that time we've seen the political mood within parliament catch up to where the public mood across Scotland has been for some time now."

He said he had detected greater levels of support from MSPs across parties but also a "willingness in principle to support it, even if there are still anxieties about the detail of how this would work in practice".

"Some of that is driven by the personal experience many of my colleagues have of a friend or loved one who suffered a bad death and have come to the conclusion that the lack of choice of an assisted death in Scotland is no longer sustainable," Mr McArthur added.

'We need the right to live first'

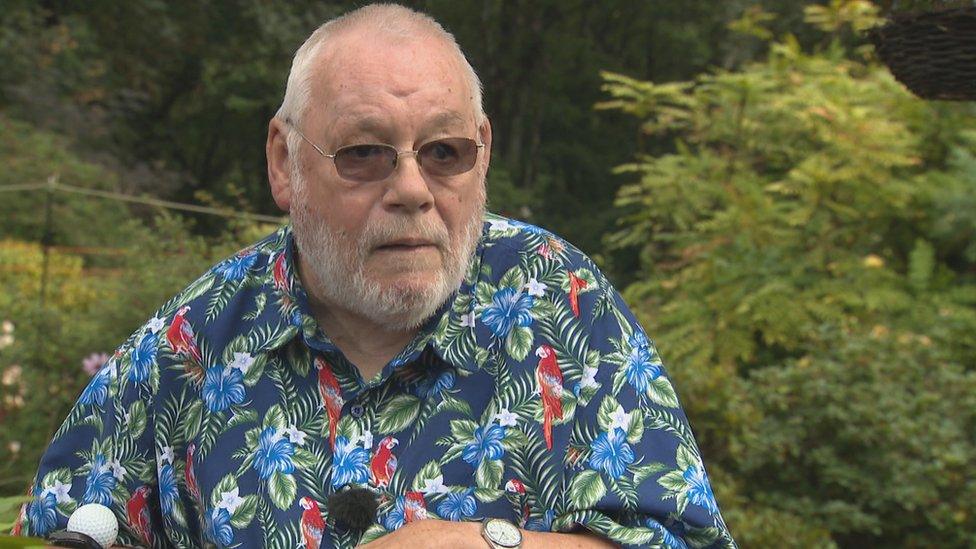

Dr Jim Elder-Woodward said no disabled people's organisations supported assisted dying

Disability campaigner Dr Jim Elder-Woodward told BBC Scotland he feared for the future of disabled people if the law was introduced.

"We are in a very difficult situation at the moment," he said. "We are not getting the support needed to live, and until we get the right to live I feel that we shouldn't have a right to die. We've got it the wrong way round."

He said that as society becomes less community orientated and more individualistic, there was a danger that "those on the edges of society, such as those with a chronic illness or disability, will become more alienated and superfluous".

"A right to be exterminated will only facilitate this societal shift towards self-sufficiency and individualism," he said.

"At the moment disabled people have a lot of struggles to get the things that we need... to be a full citizen of Scotland," said Dr Elder-Woodward, the chair of the Scottish Independent Living Coalition and an honorary research fellow at the University of Glasgow.

He said they were arguing for basic support to "live the way able bodied people live".

Dr Elder-Woodward, who was born with cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair, said he would feel more pressure if the law was changed, having already seen the pressure put on disabled people during the Covid pandemic.

"There is a possibility that it will go through, in which case I fear for the future of disabled people because no matter how confident politicians are around protecting the safeguards nobody can guarantee the future and what it will bring.

"The assisted dying bill is the edge of the wedge that might open a real disaster for disabled people in the future and that their citizenship will be gone because nobody can guarantee the safeguards of the present bill be retained in the future. Not one disabled people's organisation is in favour of assisted dying."

He added: "We want to be secure in the knowledge that we will be welcome in society in the future."

'It was a death he didn't want'

Joanne Easton joined the campaign for assisted dying after the death of her father

Joanne Easton became involved in the campaign for assisted dying after her father, retired firefighter Robert Easton, died of pancreatic cancer last year.

Mr Easton, from Hamilton, was admitted to Hairmyres hospital after chemotherapy failed to treat his tumour.

She was shocked when her dad said he would kill himself and offered to help him consider less "brutal" options, including visiting a clinic in Switzerland.

"I looked into Dignitas first of all and we just ruled it out - the amount of money it would have cost, I think it would have been about €15,000 - the fact that you had to choose the date of your death, you would have to make sure that my dad was still fit to travel," Ms Easton said.

"That would indicate that's not his time to die - if he's still able to travel he's got more time he can spend with his family."

Ms Easton then looked into euthanasia methods that could be tried at home and spent time on the dark web trying to find out where she could buy drugs that Dignitas used.

He turned them down.

Robert Easton died of cancer in a hospice after considering ways to end his own life

"If I'd got caught that would have been my life totally impacted and my dad just didn't want that," Ms Easton said.

"[The end] came really suddenly for me. He got taken into hospital and I didn't think he wouldn't come out. It was horrendous."

Palliative care at home was not an option but a week later he was given a space at the Kilbride Hospice where he spent the last two weeks of his life.

"He had brilliant care - that's one thing," Ms Easton said. "He didn't seem to be in pain a lot. It wasn't hugely traumatic but to me that doesn't matter because to me it was against my dad's will.

"My dad didn't want to die in a hospice bed, my dad had wanted to make his decision and end things when he wanted. It was profoundly a death he didn't want. That was so hard to watch.

"For my dad it was so much the mental anguish of the illness - the fact that he couldn't go out on his motorbike anymore, he couldn't go away with my mum - they loved their holidays, and he was strong and my dad did not want us seeing him in pain and he didn't want us caring for him."

Ms Easton said the proposed bill was "spectacularly written".

"I don't think there is any loophole," she said. "They've beefed it up since 2015 and in the title it says it is specifically for terminally ill adults."

Doctors "will know" if someone is being coerced, she added.

"Fundamentally it is freedom of choice. It is the individual person who is facing death. It is their choice and this bill gives their right to choose."

Among thousands of responses to the consultation, which closed in December 2021, there were 81 from organisations with 47 of them fully opposed to the proposals.

Arguments from groups representing disabled people included concerns that the bill would undermine palliative care and would put pressure on vulnerable patients to see their lives as a burden.

Dr Gordon Macdonald, from Care Not Killing, said the bill was "dangerous" and supporters had failed to address concerns "or even to engage in a debate about them".

"Evidence from other countries shows that when assisted suicide or euthanasia are legalised, the safeguards promised are quickly removed and the law is extended to include more and more vulnerable people," he said.

Former MP and MSP Dennis Canavan is supporting Care Not Killing after the death of his four children - three of them after a terminal illness.

"My children undoubtedly underwent some pain but it was minimised by caring health professionals," he said.

"As a result, my children died in dignity and I do not accept that the option of assisted suicide is necessary to ensure dignity in death."

'Pandora's box of harms'

Faith-based groups made up about a quarter of the group responses to the consultation.

Michael Veitch, from Christian charity Care for Scotland, said it was "deeply sad", and pointed out that safeguards had failed in countries that had legislated to allow assisted dying, opening a "Pandora's box of harms".

"Pressure leads to expansion of legislation, making vulnerable and marginalised groups eligible for a state-assisted death," he said.

However, Fraser Sutherland, chief executive of the Humanist Society Scotland, argued religious beliefs should not influence legislation.

"The most common reason stated in the consultation for opposition to the proposed bill was a fundamental and religiously motivated belief that human life is sacred and should not be purposefully ended in any circumstances," he said.

"Whilst we respect the right of people who are religious to hold this viewpoint and act accordingly in their own lives, we believe that Scotland's laws should be formed to reflect the views of the majority, not minority religious views."

Related topics

- Published5 July 2021

- Published18 November 2021

- Published20 June 2021

- Published2 July 2015