Without a 'distraction', who pays the bills?

- Published

Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng announced a U-turn on his top rate tax plans

A U-turn on top rate tax exposes the rest of Kwasi Kwarteng's Growth Plan to more scrutiny. The tax cuts remain very expensive, and there's a growing expectation that spending will have to pay much of the price.

It also brings us back to the much less controversial splurge on uncosted, untargeted cuts to energy bills, giving the most to those who least need it, and undermining the need to reduce energy use.

It was a 'distraction', said Kwasi Kwarteng about plans to scrap the 45p rate of income tax for higher earners.

Removing the top rate of income tax, outside of Scotland, saved those who pay it an average of £10,000, and 'the optics' - how it looks, politically - were beyond inept.

This was while price inflation was heading towards 11%, the public sector is embroiled in pay battles, and a few days before domestic energy bills were to go up 27%.

So what was it distracting us from? Well, the rest of the tax cutting package, of course, adding up to a whopping £43bn of the £45bn unfunded tax cuts in the chancellor's mini-budget of 23 September. The top rate brought in an extra £2bn.

So it was a big and expensive political U-turn, but didn't make much difference to the underlying questions of how to pay for what remains of the plan.

It also distracted us from the energy price guarantee, and its equivalent for business, costing us... we have no idea how much. It's the blankest of blank cheques.

So having been distracted, let's look again at the remaining tax cuts. The plan for raising corporation tax on profits from 19% to 25% has been reversed, as Liz Truss said she would do during the leadership campaign in the summer.

Likewise, former Chancellor Rishi Sunak's move to use higher National Insurance Contributions (1.25% more for employers as well as employees) to fund the transition to more generous social care (in England, at least) is being reversed, taking effect next month, only seven months after it was introduced.

Two further measures don't affect Scotland directly: a cut in the basic rate of Westminster's income tax regime from 20 pence in the pound to 19 pence, and a deep cut in the tax take from the transactions tax on homes, known in England and Northern Ireland as Stamp Duty Land Tax.

Medium-term fiscal plan

All that goes ahead, unless political pressure comes back from the Conservative Party. And there's far less reason for it to do so. Until, that is, the other side of the ledger is published.

We're now told the 'medium-term fiscal plan' - the sums that show Kwasi Kwarteng has his borrowing under control - will be published earlier than planned. It was to have been on 23 November. It's now looking more like this month, with an announcement about the date expected on Tuesday.

It's going to be busy for the number-crunchers at the Office for Budget Responsibility, who normally require 10 weeks to work on such government 'fiscal events'. Publication of their rough calculations was offered but rejected by Kwasi Kwarteng ahead of his mini-budget, at enormous cost to his credibility on fiscal discipline.

The figures they'll be working with are the choices the Chancellor makes to fund his tax cuts and energy support package.

These may chop and change over the next few weeks, and the OBR has to chop and change with them, until they reach a pre-agreed cut-off point.

Awkward squad

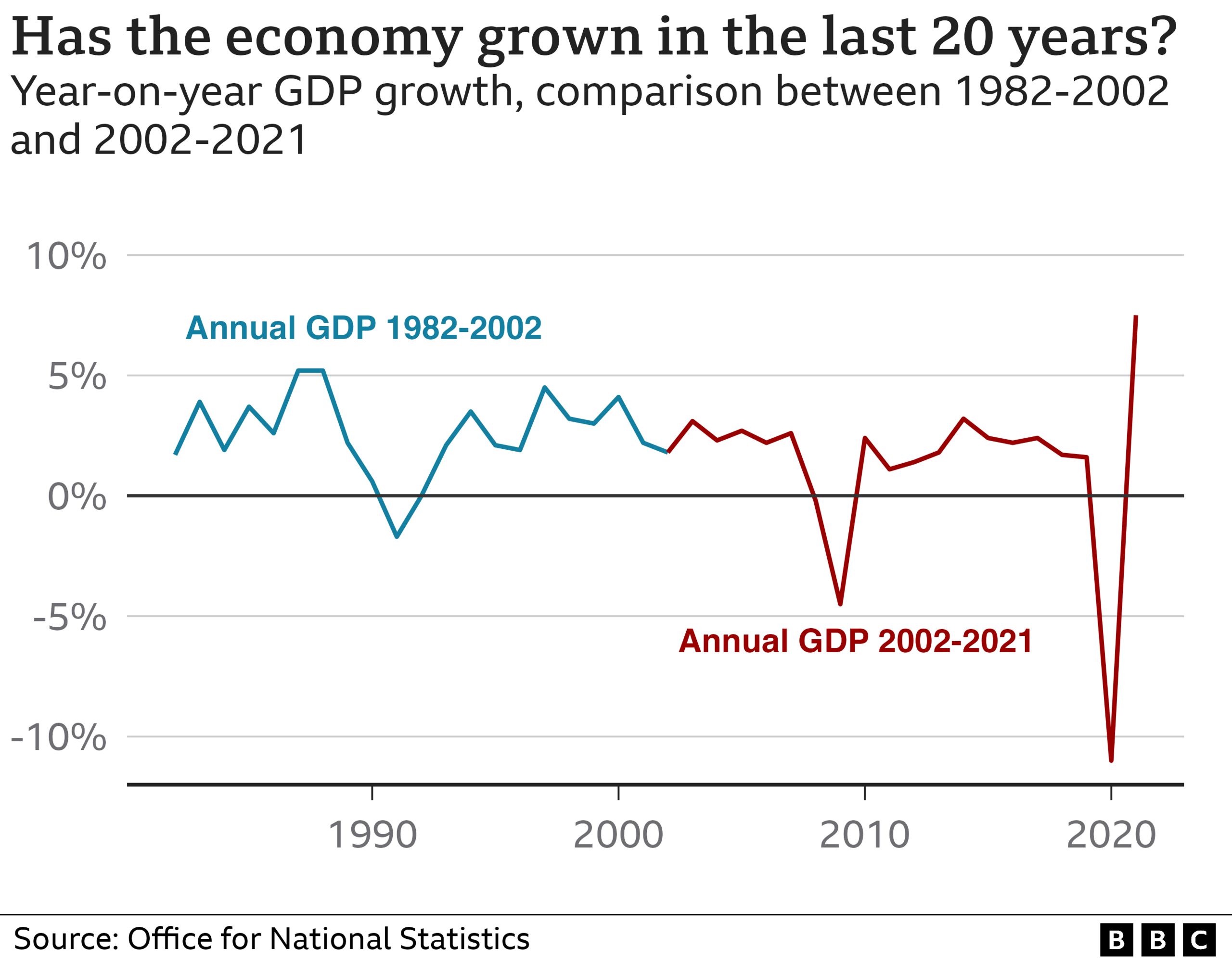

A big splurge of borrowing would make it much harder to reach the promise the new chancellor made to the Conservative conference, of getting debt down as a share of Gross Domestic Product - Britain's total economic output in a year. It sounds technical, and it is. But it's the key performance indicator that the Treasury has chosen to be judged by.

The alternative is to take a chainsaw to public spending. To many Conservatives in Birmingham, they may like the sound of that, at least until they see the possible or likely consequences.

Paul Johnson of the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) admitted that he lacks the imagination to see how deep cuts can be made, after the sharp reductions of the past 12 years.

The NHS? It's already struggling with backlogs and staff shortages, and is one of the new prime minister's top three priorities.

The state pension? Sticking to the 'triple lock' means it will go up by price inflation next year, and its recipients have a tendency to vote. Indeed, they have a tendency to vote Conservative, but they are not to be taken for granted.

Welfare benefits? A target that some would like in Conservative ranks, but Tory MPs who have already signalled their intentions as the backbench awkward squad - now with a licence to rebel against a weakened leadership - have indicated this is not a good time to be targeting those who are already least well off.

Education? Policing? None of them are easy choices for spending cuts in order to pay for tax cuts. It comes back once more to local councils, perhaps. They have taken the brunt of the cuts, also in Scotland where Whitehall's squeeze has been passed on for Holyrood to apply, and their services have been hacked back.

Brake and accelerator

However, if you are Kwasi Kwarteng, you square the circle with more economic growth, bringing in more tax revenue. Simple.

But there are several question marks over that. It is a gamble. It may not work. Just one of the problems is that tax cuts put the foot on the economic accelerator, meaning the Bank of England has to press on the brake all the harder, by putting up the cost of borrowing.

Supposing it does work, how long will this take? And if at first it doesn't succeed, how often will Downing Street try and try again? How long can borrowing take the strain when the bond markets already think this looks risky, and price UK debt accordingly?

If there is growth in the economy, Mr Kwarteng has made clear that more revenue will fuel the fire for further tax cuts. We could expect that to include the top rate for top earners.

By implication, that would mean a continuing relative squeeze on the public sector, reducing its share of national income, where pay pressure is already being stoked and where demographic pressures are rising inexorably.

Mr Kwarteng's Growth Plan goes on to lean heavily on a series of measures that have not yet been announced, on de-regulating the economy to help business grow. Many of those measures may not apply in Scotland, making it more difficult to co-ordinate the flagship Downing Street policy of low-tax, low-regulation Investment Zones.

But what we are yet to see is the reaction from those who like the regulations we've amassed over the years - on employment, the environment, agriculture, building on green belt land. Whether or not they were imposed by Brussels, even post-Brexit Britain has people who buy into them, and will surely fight for them.

Thermostat down

The other part of this mini-budget - from which we've been 'distracted' - is help with energy bills. Because that has widespread support, so far as it goes, across politics, business and anti-poverty campaigners, there isn't much discussion of the package we've got. And which of us does not like government absorbing the risk of prices remaining very high and very volatile?

But it might be worth taking a moment to recall what the International Monetary Fund, Moody's credit rating agency and others said last week: the flat rate cap on unit prices is not targeted at those who need help most. Instead it's most generous - in cash terms - to those, in big homes and those running gas-guzzling business.

So it increases inequality, which those overseas observers already see as a weakness of the British economy.

It also masks the price signal of higher energy prices, as an incentive to use less or to shift to alternative sources of heat and power.

We're reminded of that by the message from energy regulator Ofgem that Britain could be heading for a gas supply emergency this winter, meaning that some industry's may have to power down or switch off, and one of those industries could be the gas-fired electricity generators.

Of course, Liz Truss blithely promised, while a leadership candidate, that there would be no rationing on her watch. That's another failure to understand markets, and her lack of her control over them, that could come back and bite the Prime Minister.

But as October chill, rain and wind billow in from the Atlantic, it's not too late to turn down the thermostat in Downing Street, as an example to others.

In any case, the politics of recent days have surely been generating enough renewable heat to make quite a dent in Britain's demand for natural gas.

Related topics

- Published3 October 2022

- Published3 October 2022

- Published2 October 2022