Mesh surgery women not given accurate advice, says report

- Published

Mesh implants were used to treat conditions some women suffer after childbirth, such as incontinence and prolapse

Women who underwent mesh surgery were not given accurate information before the life-altering procedure, a case review has found.

The study also said poor communication between patients and doctors led, in some cases, to mistrust.

Medical notes were often misleading or did not detail the surgery that had occurred or its outcomes.

The review spent two years looking at the cases of 18 women who received transvaginal mesh implants.

It has now called for a comprehensive register to be set up to keep track of women who have had operations to remove mesh in Scotland, abroad and privately.

The Transvaginal Mesh Case Record Review by Glasgow Caledonian University makes a series of other recommendations, including:

Better aftercare following surgery

Clear language so patients understand exactly what surgery is going to achieve.

The review, led by Prof Alison Britton, looked at more than 40,000 pages of records.

Prof Britton said a new register was vital to improving communication and final outcomes.

She told BBC Scotland: "Some women are going to America, or going elsewhere for private surgery. Very often it's not only revision surgery to remove medical mesh devices, it can be other sorts of surgery like cosmetic surgery.

"If we don't know what they've had it's going to be very difficult to manage the resources to be able to support these women in the future."

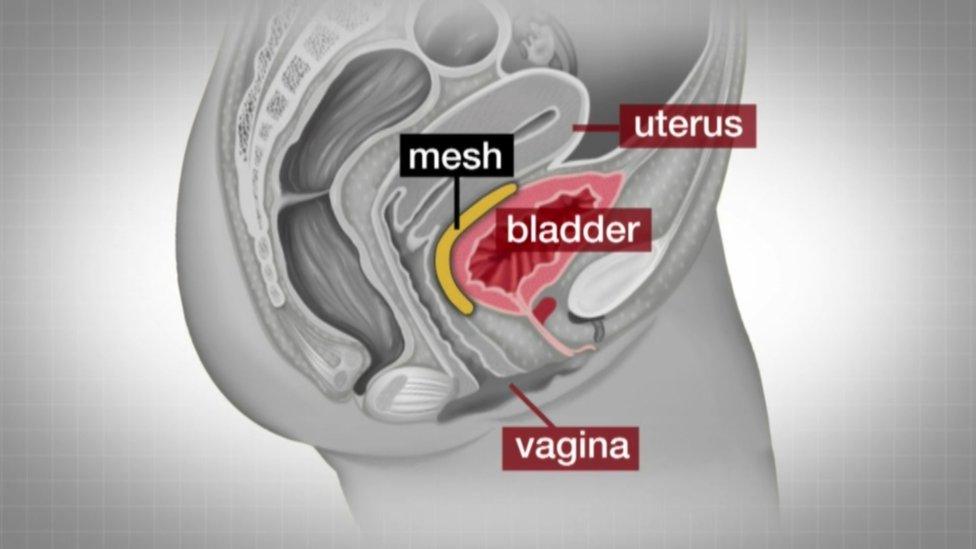

Mesh implants had been used to treat conditions some women suffer after childbirth, such as incontinence and prolapse.

But its use was stopped in Scotland after hundreds of women were left with painful, life-changing side effects.

The NHS has currently paused the technique in the UK unless no other option is suitable.

There is still no clear picture of how many women experience complications, but there have been serious questions surrounding the introduction and promotion of the procedure.

Prof Britton's study looked into the cases of 18 women who had mesh surgery

Prof Britton added: "Every patient is entitled to expect and receive accurate information both before any treatment is chosen and to be advised on the effectiveness and consequences of any intervention.

"If clear and commonly understood language had been used to explain to women potential treatments and outcomes, even if these were uncertain prior to surgery, this may have alleviated many of the issues that subsequently arose over the course of their clinical journey.

"In a number of the cases, we observed a lack of clarity in the case records documenting the nature and potential outcome of mesh revision surgery. Some notes were misleading, but other cases did not bear any reflection to the surgery that had occurred, nor its outcomes. These matters may have not come to light, without the commissioning of the review.

"We recognised that women had concerns about the accuracy and content of their case records and that this required to be explored. If they were to move forward with their lives, the women needed to have it acknowledged that they were not imagining the circumstances in which they find themselves."

What are mesh implants?

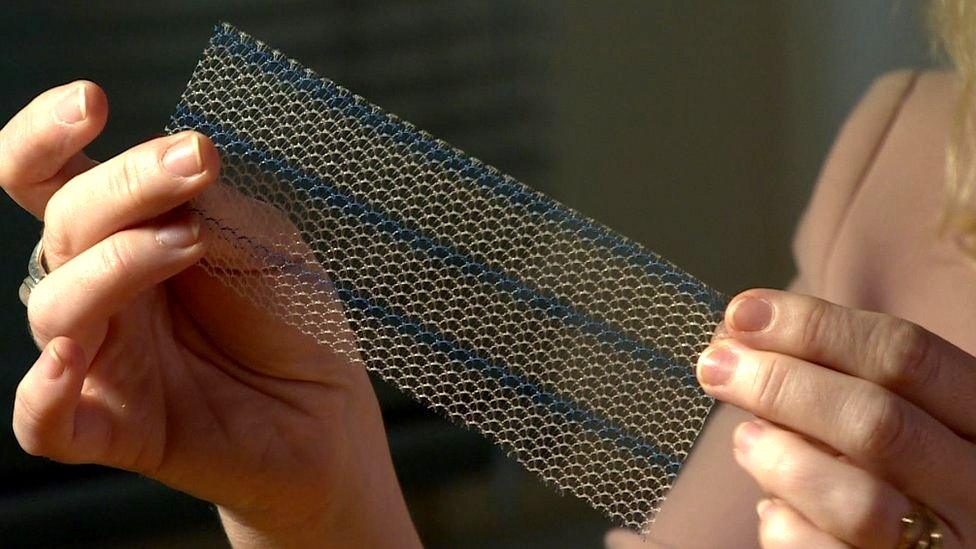

The mesh is made of polypropylene, a type of plastic

The mesh, usually made from synthetic polypropylene, is intended to repair damaged or weakened tissue.

Over 20 years, more than 100,000 women across the UK - including more than 20,000 in Scotland - had transvaginal mesh implants. They are used to treat pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence, often after childbirth.

While the vast majority suffer no side effects, the use of mesh in Scotland was suspended except in "exceptional circumstances" in 2014 after it emerged some women suffered painful side effects.

Use of the procedure was halted in 2018.

Once the mesh is implanted, it is very difficult to remove.

'We still don't feel we're being listened to'

Lisa Megginson, 52, is one of the 18 mesh survivors whose story was recorded in the latest review.

She travelled to have her mesh removed at Southmead Hospital in Bristol in April 2022 and is hoping to return there for further corrective surgery because she has "no trust" in her health board, NHS Tayside.

Lisa, from Kinross, said: "Some things have improved, but not enough that we feel we are being listened to or that we are trusting of clinicians.

"I have had more support and care from Bristol than I've had here.

"Nobody in Scotland has asked if I'm OK. I've had no communication from my health board.

"Nobody has written to me to ask if I need any follow-up care. Am I discharged? I don't even know.

Lisa said a more patient-focused approach was needed with more follow-up.

She added: "Sometimes you think your care is going to be good and sometimes you know your care is going to be bad.

"I just want to get off the merry-go-round because at the moment you feel like you're going round in circles."