Are Scotland's prisons fit for purpose?

- Published

Richard Sharples faced being jailed at HMP Barlinnie in Glasgow

When an Irish judge blocked a man's extradition to Scotland on humanitarian grounds, it raised questions about the state of Scotland's prisons.

Mr Justice Paul McDermott said Richard Sharples faced being locked up for 22 hours a day in less than 10ft (3m) of space.

He said Scottish authorities could not guarantee that Mr Sharples' complex mental health needs could be met at either Barlinnie or Low Moss prisons.

And he raised fears that there was a "real and substantial risk of inhuman or degrading treatment", the Times reported, external.

The Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service says it is considering the terms of the ruling.

Mr Sharples, 24, is wanted in Scotland in connection with a firearms offence and a serious assault which endangered the life of another man.

Were the Irish judge's concerns about Scotland's prisons justified?

Are prisoners locked up for 22 hours a day?

During the early months of the pandemic, the Scottish Human Rights Commission raised concerns that some prisoners were being confined to their cells for 24 hours a day., external

Some had no opportunity to shower, exercise outdoors or telephone their family, according to the commission's chairwoman Judith Robertson.

Meanwhile HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland found that for large parts of 2021/22 "too many prisoners were locked up for more than 20 hours a day, external, sometimes 22 or even 23 hours a day".

In Wendy Sinclair-Gieben's November 2022 report, she expressed concern that prisons were unable to "deliver anything more than a very restricted regime" and the return to normality after Covid was slow.

However the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) insists that this is no longer the case and even when pandemic restrictions were in place prisoners had access to fresh air, exercise and other activities.

"Thankfully, like Scotland as a whole, we are in a far better place," a spokesman said.

"All individuals have daily access to open air, visits from friends and families, education sessions, gym and other forms of purposeful activity, including addiction support, wellbeing services and other programmes."

Mr Sharples could have been sent to HMP Low Moss in Bishopbriggs

The amount of time spent on "purposeful activities" varies by prison however, according to information obtained by prison reform charity Howard League Scotland, external last September.

They found that prisoners at HMP Barlinnie in Glasgow spent 1.05 hours a day in "purposeful activity"; at HMP Low Moss, Bishopbriggs it was 4.28 hours.

Katrina Morrison, a lecturer in criminology at Napier University and a member of Howard League Scotland, said some prisoners prefer to stay in the cells, where they feel safer.

"People shouldn't have to choose between time out of their cell and feeling safe, they should be able to have both," she added.

Do prisoners have just three metres of space?

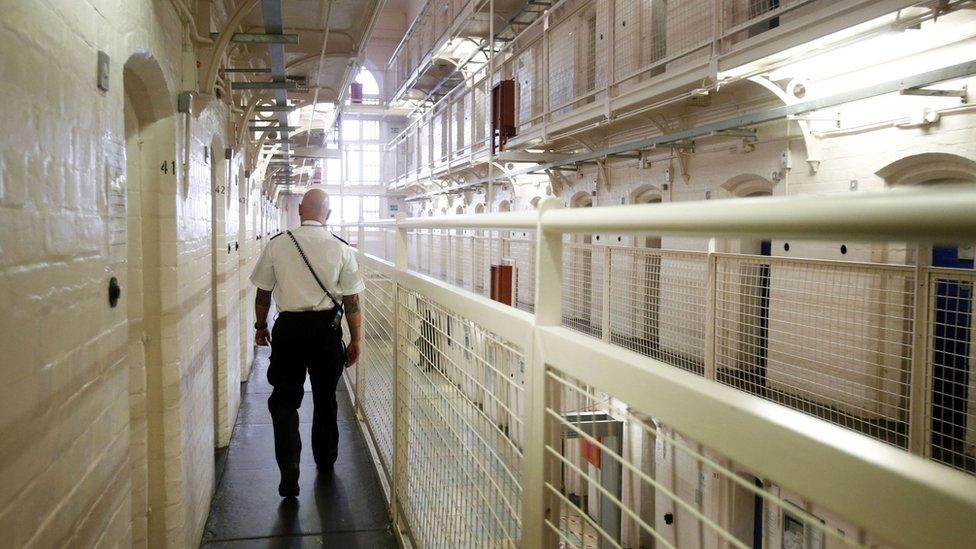

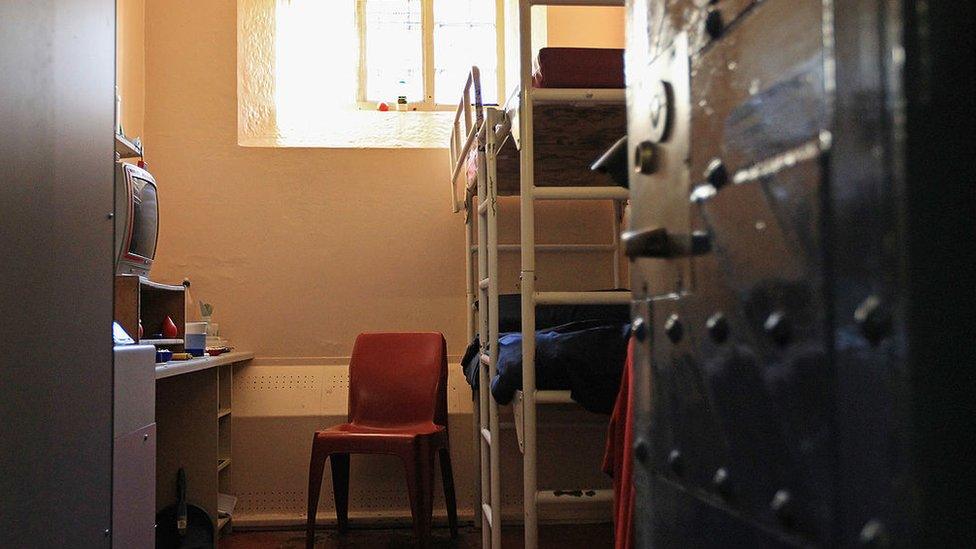

Barlinnie prison is an overcrowded, aging Victorian building, "ill-suited to the modern prison system", according to the chief inspector of prisons.

She says many prisoners at the Glasgow jail have to share a cell space of 6sq-m, which includes a partitioned toilet.

Single cells should be 6m² and those which are shared should offer at least 4sq-m of living space per prisoner, according to the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture, external.

A cell in HMP Barlinnie was photographed in November 2011

Overcrowding is also an issue at Low Moss, despite it only opening in 2012.

It was designed to hold 784 prisoners but an increased prison population saw that figure rise to 884.

That means cells designed to hold single prisoners have been converted to double cells and, according to inspectors, they are too small.

Why are Scotland's prisons so overcrowded?

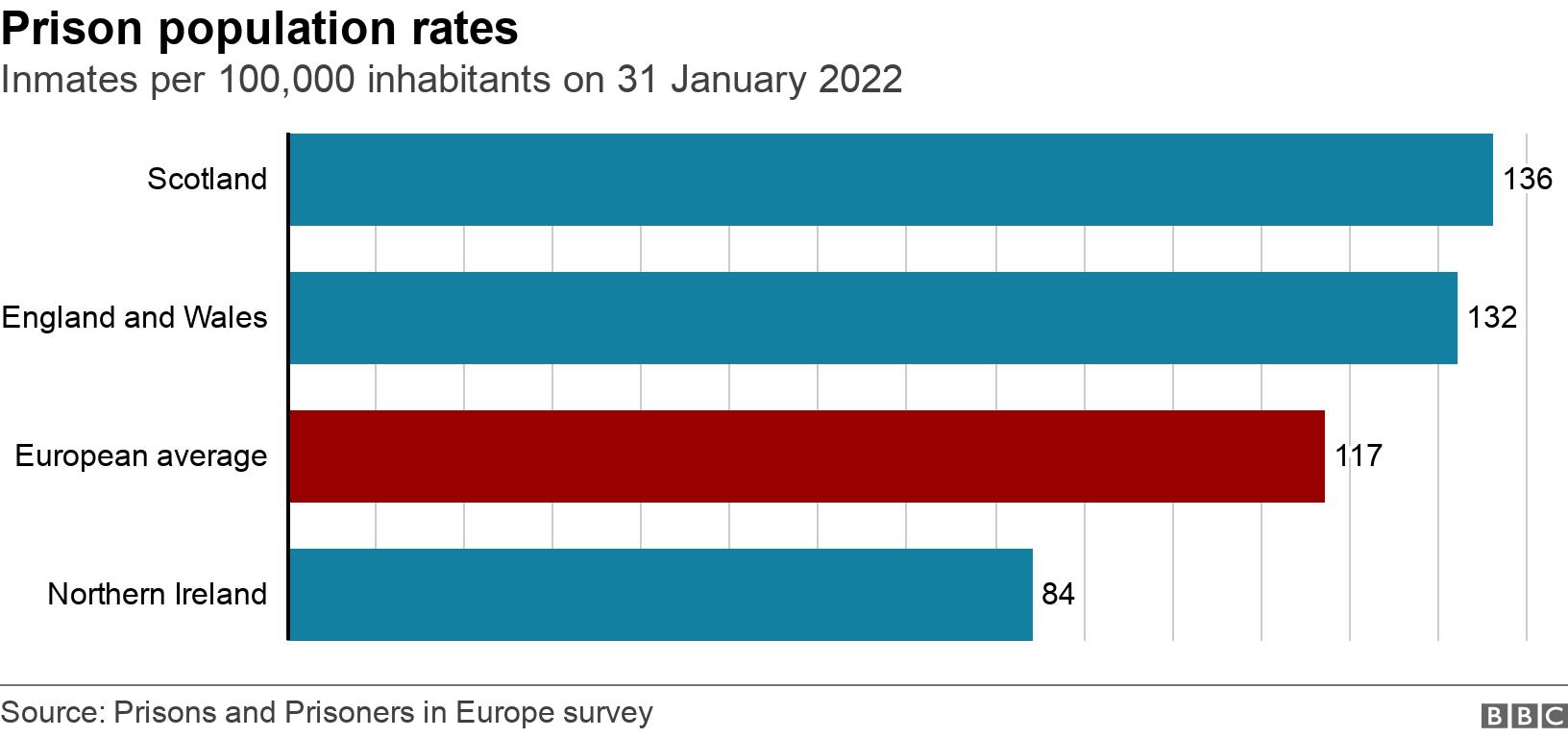

Scotland sends more people to prison than most other European countries, but a sizeable minority of them have not even been sentenced for a crime.

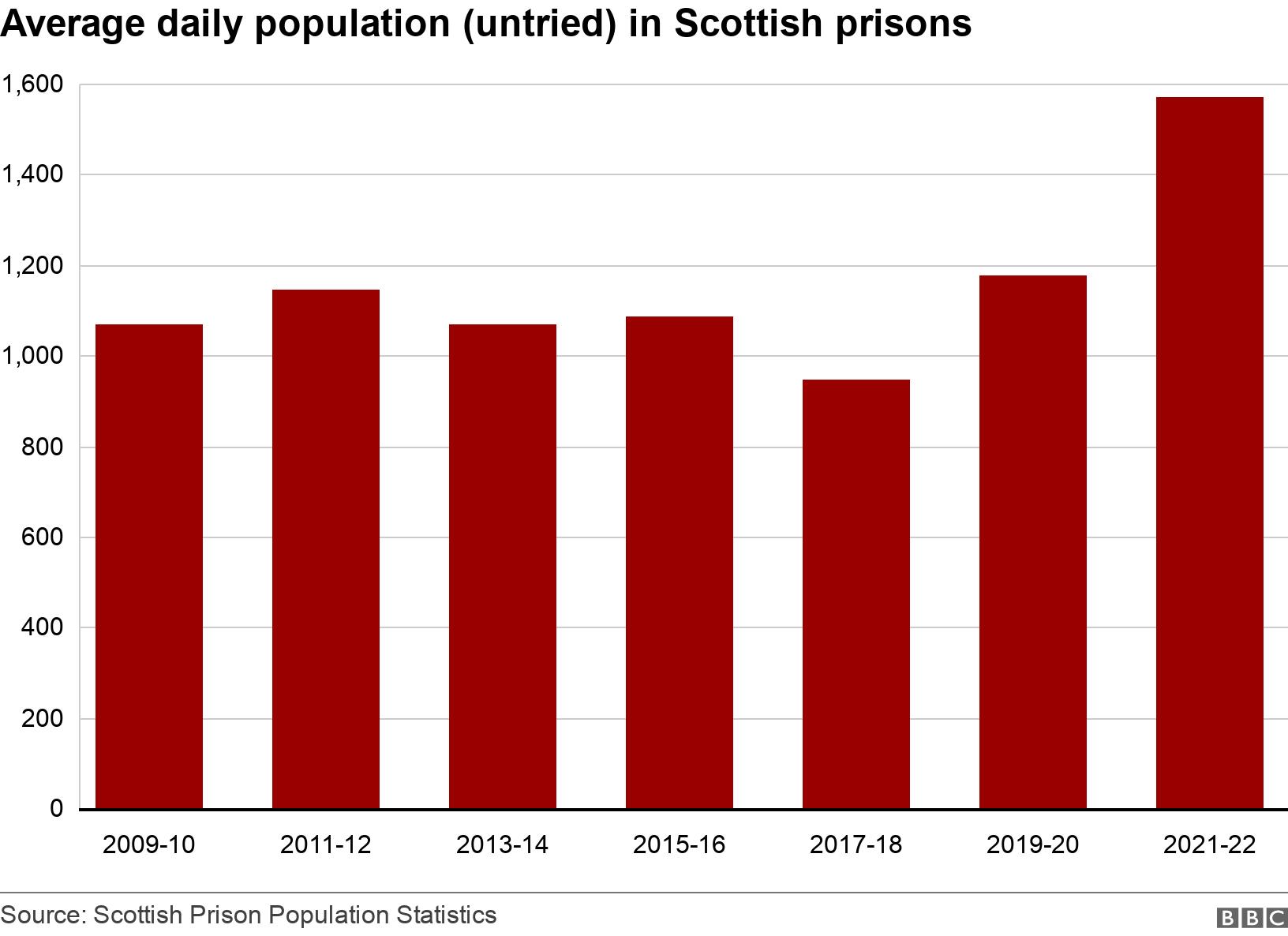

More than a quarter of the 7,775 people in Scotland's prisons are awaiting trial, deportation or sentencing, according to the latest official statistics, external.

They are known as remand prisoners and their numbers have increased as a proportion of the prison population from 19.9% in 2015 to 28.4% in 2023.

Lawyers say they have clients who have been on remand in Scottish prisons for up to two-and-a-half years.

They blame the effects of the pandemic, which led to court backlogs, for the increased numbers.

Tommy Ross KC, a former president of the Scottish Criminal Bar Association, told BBC Scotland that urgent action was required.

"We need plea negotiations. We need the Crown to prosecute fewer cases. We need sheriffs to be more charitable when it comes to bail decisions.

"We need to think about half-way houses between bail and custody, maybe putting people in hostels with conditions that they stay."

The SPS said it recognised that its population had steadily increased in recent months.

"While it is not for us to determine who should be remanded in custody, the impact on our establishments is significant," a spokesperson said.

"We are managing an increasingly complex prison population. Certain demographics are unable to be located in certain establishments, or even in the same area within an establishment.

"When our population increases, the challenge these complexities present becomes ever more acute."

And the chief inspector of prisons has warned that the increase in remand prisoners is likely to adversely effect the SPS's ability to manage a "decent, rehabilitative and humane regime".

The Scottish government said prison was needed for those who pose a risk to public safety but it was taking action to address the high imprisonment rate.

"That includes ongoing investment in community-based interventions which we know are more effective at reducing reoffending than short-term imprisonment," a spokesperson added.

Can Scottish prisons deal with complex mental health needs?

The High Court in Dublin heard that Mr Sharples had ADHD, anxiety, depression, insomnia and Asperger's syndrome.

Mr Justice McDermott raised concerns that Mr Sharples would not be able to cope with prison life and said he had not received specific assurances from the Scottish authorities.

He pointed to a 2022 Scottish government report on the mental health needs, external of the Scottish prison population which found a "poor recognition of neurodevelopmental disorder in UK prisons".

It also found that, although ADHD is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder among inmates, it is rarely diagnosed or treated by mental health services.

Yet those with such conditions are more vulnerable, and face issues relating to bullying and associated health conditions.

In relation to wider mental health problems, the report by University of Edinburgh researchers found that people in prison were "far more likely to have a current mental health need than not".

They found that people on remand were particularly vulnerable to mental health problems.

SPS data shows that two-thirds of deaths by apparent suicide in prison occur during the first three months of custody.

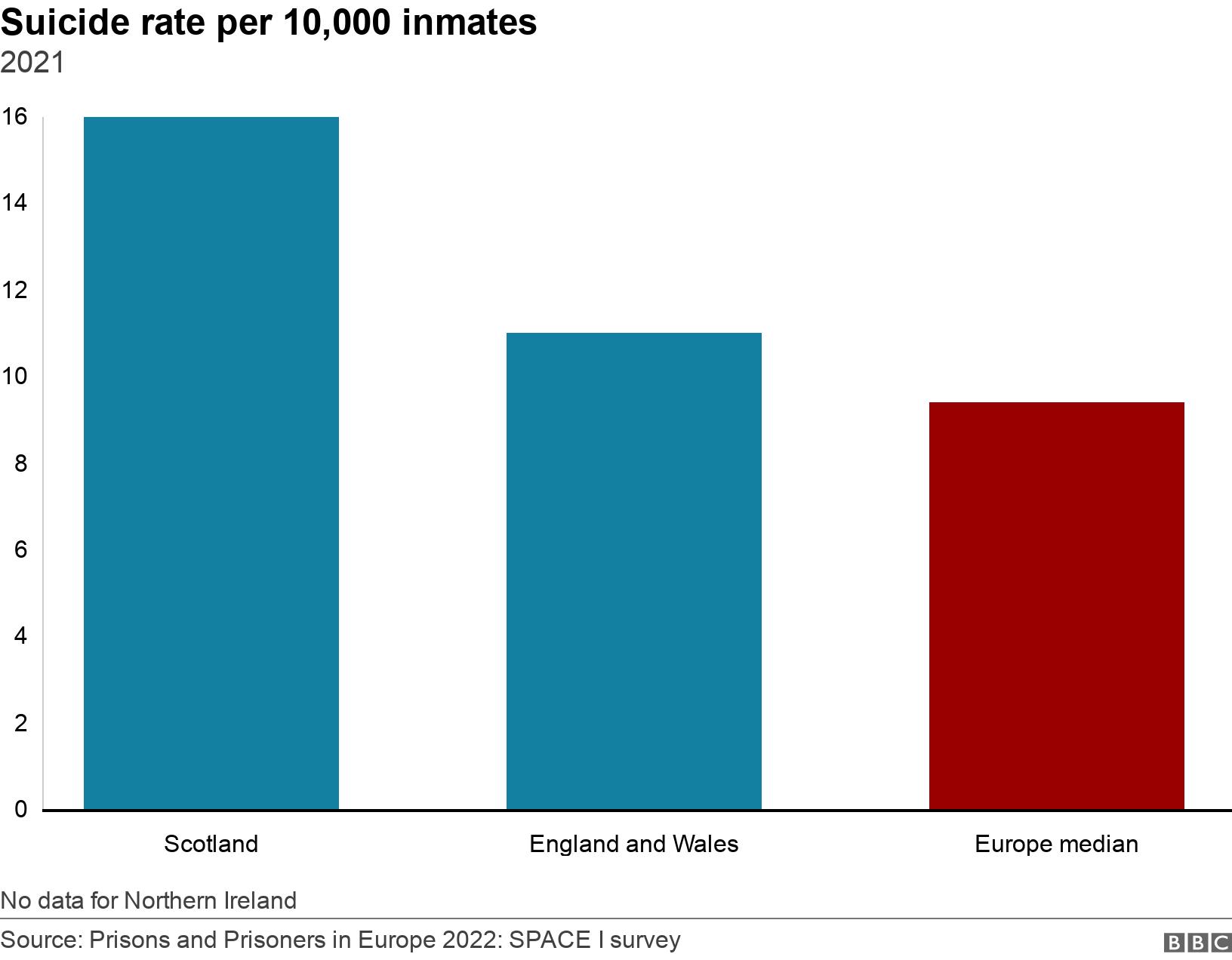

And Scotland's prisoner suicide rate - 16 per 10,000 inmates - is among the highest in Europe, where the median rate is 9.4 per 10,000.

The report concluded that existing provision to support the mental health of people in prison does not adequately meet their needs.

They called for "fundamental change in the approach to prison care and prison mental health services".

A SPS spokesperson said there has been an increased demand for health and social care services, partly due to the prison estate's ageing population.

"We also work with partners in the NHS, Fife College, and the third sector, to identify and then support anyone who enters our care with a neurodevelopmental disorder," they added.

"SPS takes an individualised and person-centred approach to identifying the needs and capabilities of all those in our care, including people who may be neurodivergent or have learning disabilities, to ensure the necessary shared support plans and interventions are in place."

The Scottish government said: "The health, safety, and wellbeing of those in prison is a key priority. The SPS works closely with NHS partners to ensure appropriate measures are in place to support those individuals including those with complex needs on a case-by-case basis."

- Published13 December 2022

- Published22 January 2021

- Published4 February 2016