Behind Bars: Inside Dumfries Prison

- Published

It is home to some of Scotland's most notorious criminals - a place where murderers, paedophiles and rapists are confined for years at a time.

With up to 173 inmates, outsiders could be forgiven for assuming that HMP Dumfries is a tense, violent and secretive establishment.

The reality is very different and a recent glowing report by HM Inspectorate of Prison described it as a "safe prison, if not the safest in Scotland".

Prison governor Phil Kennedy puts it down - primarily - to the relationships between staff and prisoners.

As it is a relatively small prison, its 140 operational staff get to know their inmates well.

During a tour of the estate, it was clear there is banter but there is also mutual respect.

Up to four men can share a cell in Dumfries prison but in this case only two were occupied

Inmates spoke warmly of officers who helped them when they first arrived and those who have supported to them to gain skills and qualifications.

The prison governor says it is not up to his officers to punish the inmates for crimes committed on the outside.

He says: "We should be working to rehabilitate them, to make them decent citizens, to put them back out into a safer community and make them feel that they can do something worthwhile, that they have self-worth, that they are able to contribute positively.

"The loss of liberty is the punishment and that's why courts put them into prison."

Mr Kennedy adds: "It's really important for us to work with offenders, starting off with some of the positive aspects of their life, working on the negative aspects, and getting them back up into a position where they can actually believe in themselves and go out and contribute."

The prison is split into 14 residential areas. Some parts house remand prisoners who are awaiting sentencing by the courts; others are home to short-term local inmates serving sentences of less than five years.

There is also section of the jail reserved for long term and high profile prisoners. Disgraced politicians, former police officers and ex-prison staff have spent time in the cells at Dumfries.

Dumfries prison: In numbers

Built in 1863 as the local prison to serve the south-west of Scotland

There are about 173 prisoner placed in 14 separate areas

Two thirds of the cells can hold two or more people

Forty cells do not have their own toilet - prisoners must ring a bell to be allowed to use separate facilities

Prisoners who chose to work can earn between £7.40 - £12.40 per week to spend in an on-site shop

In the past 12 months, there have been three instances of low level violence

There are strict rules about what prisoners are allowed in their cells (blades, drugs, mobile phones and internet-connected games consoles are banned; TVs, stereos and basic games consoles are permitted).

If they are found in breach of the guidelines, they could have their privileges removed, be put in solitary confinement or even moved to another jail.

And if they are involved in a fight or found in possession of a mobile phone, they will be automatically reported to the police.

Deputy Governor Andy Hunstane says many of the prisoners stick to the rules because they do not want to risk being moved to another prison, where they might be the focus of hostility from other inmates.

They are also kept busy in work projects - joinery, cleaning, cooking, gardening - as well as educational classes, gym sessions and meetings with social workers, addiction agencies and other outside groups.

In the joinery workshop, inmates make furniture, planters and toys for local charities and not-for-profit groups

The prison is currently piloting a radical new project aimed at helping repeat offenders break their pattern of behaviour.

Through the Airmaps scheme, prisoners work with case-workers to identify their own talents and strengths. They believe that, with encouragement, it will shift their focus from the criminal aspect of their lifestyle.

Kerry Payne, a residential officer who is leading the project, says: "We've had an incredible amount of offenders that are fantastic at art but people don't see that bit, they see that they break into houses.

"It's shifting that to say, 'well you're really good at that, why not try this? Why not try that?'.

"The guys in here love their PT. They're probably the healthiest that they've ever been when they're in here but they don't do it on the outside.

"It's trying to put things in place to help that offender but it's not about making big steps. We don't expect them to get out and never offend again. People make mistakes. But it's about picking themselves up and moving on."

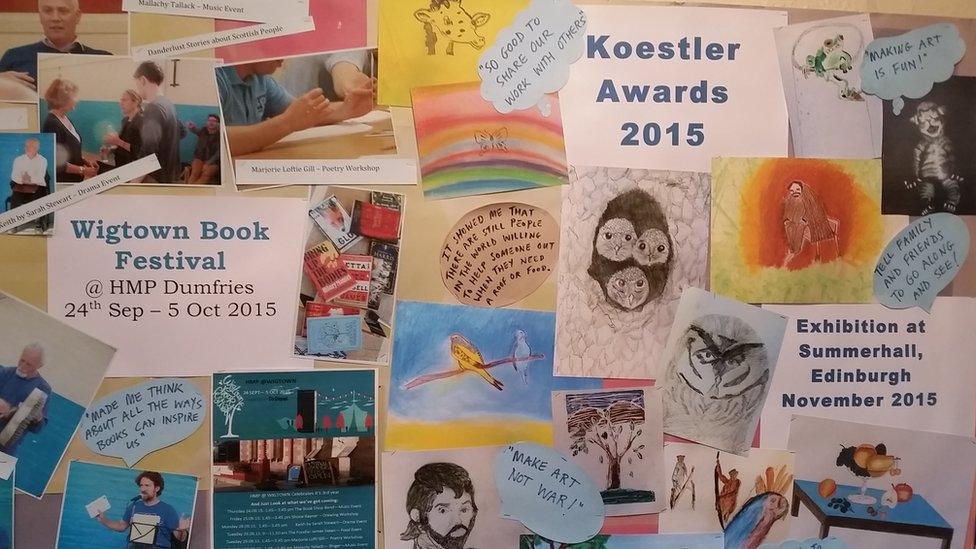

Many of the prisoners take part in art classes and some have their work displayed in exhibitions

Prisoners are entitled to about four visits from family and friends every month. And where appropriate, fathers of young children are encouraged to maintain regular contact with their families.

Special play sessions are arranged so that men can - literally - get down on the floor of the visitors' room and play with their children. On other occasions, they can invite their family to cook and eat a meal with them in a kitchen that has been set up in the prison.

It is beneficial for both the inmates and their families that their relationships are maintained, according to Michael Birkett, the prison's family contact officer.

He added: "We run a group for guys with children under five and what we discuss is children's development through play and eating healthily and drugs and smoking and things to try and make them realise that the children are the ones who are actually missing out, being hurt by this.

"So rather than thinking of themselves when they're doing whatever they're doing, they need to take a step back and think of the wife and the child out there as the one's being punished to hopefully change their attitudes towards the crimes they're doing."

We should be working to rehabilitate them, to make them decent citizens, to put them back out into a safer community and make them feel they can do something worthwhile.

Their work is in the best interests of the offenders, their community - and the staff, according to Justin Cowan, a Throughcare support officer who oversees the transition from prison to liberty.

"They're going to be released into our community so if we want to live in a safer community, the only way we're going to do that is to try and help the people to build their lives up," he says.

"If I can help somebody get a job, get off drugs, then its not my house or my mum's house that's getting broken into. My friends and families aren't going to become victims of crime - or their chances are greatly reduced."

The men take their lunch and dinner in the communal dining hall - they eat their breakfast in their cells

Inmates learn industrial cleaning in a specially-kitted out room

- Published4 February 2016

- Published19 November 2015