Scottish art takes centre stage after £38m revamp at National Gallery

- Published

Sir Edwin Landseer's Monarch of the Glen occupies a prime spot in the first gallery

"It's been a complex project," admits Sir John Leighton, the director-general of the National Galleries of Scotland.

A £38.62m revamp has created 12 brand new galleries for Scottish art underneath the original 19th Century building on Edinburgh's Mound.

But it is opening five years later than originally planned and has cost double the original price tag.

On my first visit to the new gallery, ahead of its official opening on Saturday, I didn't have to look hard to see the obstacles they had to overcome.

The work took place in a very constricted site above the main Edinburgh to Glasgow railway line and beneath a historic building.

The curve of the floor in the new galleries follows the shape of the railway tunnels beneath, and trains to and from nearby Waverley Station can be seen from the windows - and heard - rumbling far below.

The new gallery was created beneath the original 19th Century building

Above ground, at the foot of the Mound sit the original two Victorian galleries, both designed by the same architect, William Henry Playfair.

The original gallery devoted to Scottish art was created in the basement in 1978 but it quickly became clear that it could not accommodate the vastly expanded collection of more than 60,000 works.

And there was the additional problem of many artworks being too large to be moved down to the basement space - an issue which has been resolved with the new space's vertical picture lift.

Visitors were not convinced about the original basement space either, with only one in six Scottish gallery entrants making their way downstairs.

The original plan was to expand the gallery into the 70s office space alongside the basement, extending out into Princes Street Gardens, and 5m (16ft) over the railway line.

Planning permission was granted in August 2016 but having failed to reach agreement, the project had to be reworked and relaunched in 2018, when it was estimated to cost £22m.

The new galleries display Scottish art over a 150-year period

The first phase was successfully completed in 2019 with a new entrance in Princes Street Gardens, a terrace and landscaping, and a café and shop.

But when work began on the other end of the building and it was fully stripped back to its concrete structure, engineers discovered other problems including undocumented asbestos, obstructions from previous developments, and deeply buried layers of dense concrete which required removal.

The Covid pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis pushed costs higher. In the end, the project cost more than £38m - including £16m from a fundraising campaign.

The project is even more personal for gallery director-general Sir John Leighton, who will retire at the end of this year after 18 years in the job.

Did he ever consider moving the Scottish gallery plans to an easier site?

"No," he says.

"It was important to have the best of Scottish art right here in the centre of the country, in the symbolic heart of the nation."

The new Scottish gallery sits below the original 19th Century building

Sir John says it was important to show the "interchange with international art" because Scotland's art grows and develops in contact with the rest of the world.

"It's an outward-looking story so it's really important we do it here, in the National Gallery, right in the centre of the capital," he says.

Tricia Allerston is chief curator of European and Scottish art and it has been her job as co-director of the new Scottish Galleries project, to select what goes on the walls of the 12 new galleries.

"That's the fun bit," she says.

"To see what we have, talk to colleagues, talk to visitors and see what works."

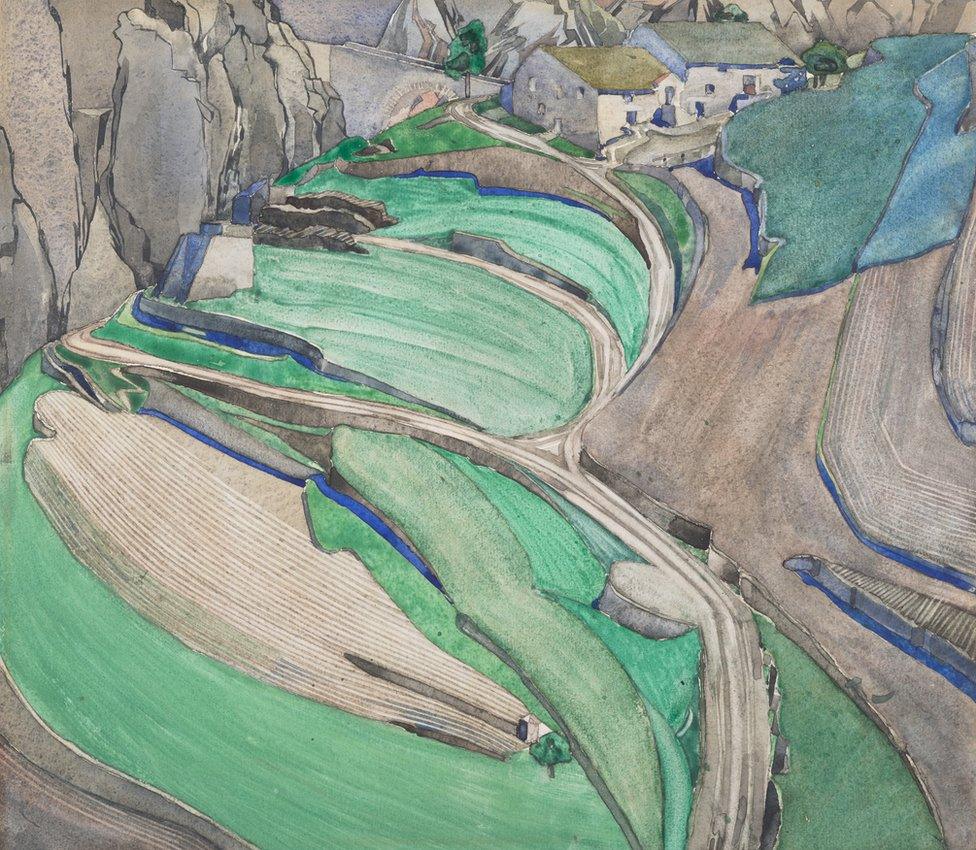

Charles Rennie Mackintosh's Mont Alba from about 1924-27 when he lived in France

The galleries aim to show the story of Scottish art across 150 years (from 1800 to 1945) and there are some obvious poster boys.

Sir Edwin Landseer's Monarch of the Glen, purchased after a public fundraiser by the galleries in 2017 occupies a prime spot in the first gallery (or the last, depending whether you enter via the Mound or the Gardens).

Directly opposite Landseer's famous stag is a towering portrait of Sir Henry Raeburn, whose famous work, The Skating Minister, remains upstairs - falling just outside the timeframe.

Nearby, a portrait of Callum the dog divides opinion.

Painted by John Emms in 1895, it depicts a Dandie Dinmont terrier, which originate in the Scottish Borders and are named after a character in the Walter Scott novel Guy Mannering (Scott had two Dandie Dinmonts called Ginger and Spice).

In 1919, Callum's owner James Cowan Smith, bequeathed £52,257 (more than £2m in today's money) to buy art for the gallery with one condition, the portrait of Callum must remain on permanent display.

It is thanks to Callum that the galleries now have works by Velazquez, Goya, Raeburn, Constable, Sargent and Mackintosh and are still spending the money today.

One of the earliest paintings in the national collection has also been rarely shown in Edinburgh. Christ Teacheth Humility was created by Robert Scott Lauder for a competition to find new works for the Houses of Parliament.

It is a monumental biblical painting, with a recognisably Scottish backdrop.

Christ Teacheth Humility by Robert Scott Lauder underwent conservation in an empty gallery during the pandemic

Three metres (9.8ft) wide, and 2m (6.6ft) high, it was exhibited in 1847 in Westminster Hall where despite widespread admiration, it didn't win.

The painting was later bought by the Royal Association for the Promotion of the Fine Arts in Scotland in the hope it would help establish a Scottish National Gallery.

And while it didn't happen then, more than a century later, it has found its space in the new galleries.

Fresh from conservation work - in an empty gallery during the pandemic - it's one of a number of works which visitors can take a closer look at.

"Because we didn't have space, very often pictures were hung on top of each other and you couldn't see the detail," says Tricia Allerston.

"What we wanted to do was let people get up close and see how they are painted."

"If you pick up a history of Scottish art, or look online, you will see many of these works but you may not have had the opportunity to see the real thing.

"Some are smaller, bigger, you see the textures, you see the astounding detail up close."

Phoebe Anna Traquair - The Progress of a Soul: The Entrance (1895)

A case in point are four life-sized tapestries by Phoebe Anna Traquair, an Irish-born artist whose work as an illustrator, painter and embroiderer was central to the arts and crafts movement in Scotland in the early 20th Century.

She's one of a number of women who feature in the new galleries.

"We're keen to surface as many women as we can but the further back in history you go, the harder that is," says Tricia.

"In the 20th Century, there's a chance for women to go to art school, to make their own work."

But there's an added challenge in representing female artists. Many are working with fragile materials, or creating work in situ.

"Lots of women like Phoebe Anna Traquair worked on large scale murals - and many of the ones here in Edinburgh which were part of buildings were destroyed," says Tricia.

"She was one of several really dynamic women, who were painting these massive works on walls and very few still exist."

Another work brought back into the light is by the artist Ann Redpath. On one side is one of her most famous works, The Indian Rug (or Red Slippers) but the other side of the canvas contains a rarely-seen landscape, both painted in 1942.

"We had this space at the window and we wondered what to show, so we started to think of artists who painted on both sides of the canvas," says Tricia.

"A lot of artists do, because painting materials are very expensive and Ann Redpath was also painting during the war when materials were scarce so we have these two lovely paintings from the same period."

With 60,000 works to choose from - and a mere 160 on show - there's plenty of scope for changing the galleries around and Tricia is keen to hear what visitors think about the choices they've made so far.

"The hope is that we change either end of the galleries every three years," she says.

"We start with the power of story, and these are the stories we've chosen to tell, but there are many other stories and many other paintings we could have shown and we hope we can keep shedding light on the different parts of the collection and just showing how fabulous 19th Century art can be."

- Published28 April 2021