How can we stop children vaping?

- Published

When Herbert A Gilbert filed the first patent for an electronic cigarette in 1963 he was a man ahead of his time.

A two-packet-a-day smoker, working in the family scrap business in Pennsylvania, he saw his invention as a simple way of taking harmful smoke out of a habit that was then a normal part of everyday life.

It took four decades for the idea to catch on. By the early 2000s the world had woken up to the health harms of tobacco; a combination of restrictions and taxation were finally making serious inroads into the habit.

Electronic cigarettes, or vaping devices, were promoted as a far healthier alternative to tobacco, which they undoubtedly are.

Sales grew steadily but not spectacularly until the manufacturers discovered a lucrative new market. Children.

Cherry peach lemonade, watermelon bubble gum, strawberry ice cream, gummy bear... the flavours on offer for disposable vapes provide a big clue about who is being targeted.

They are typically brightly-coloured and so small they are easily concealable.

Now the Scottish government has backed the recommendations of a four-nations consultation on vaping and smoking in young people.

Restrictions on vape flavours and promotion will be among the measures enacted by legislation at Westminster, but a planned ban on single-use vapes requires a separate Scottish law.

It is already illegal to sell any vape to anyone under 18, but the UK government said disposable vapes - often sold in smaller, more colourful packaging than refillable ones - were a "key driver behind the alarming rise in youth vaping".

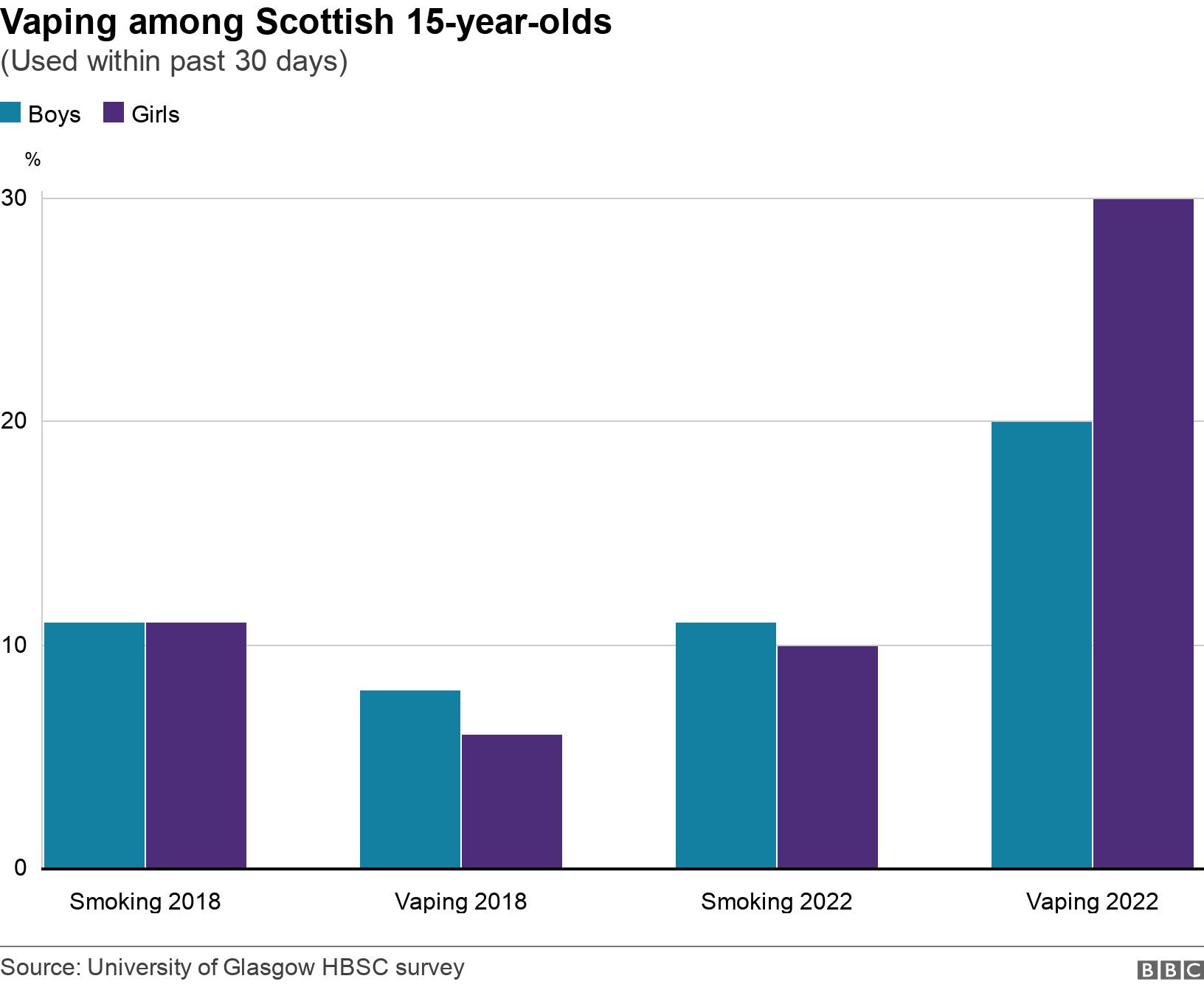

A recent survey of health-related behaviour among Scottish schoolchildren, external found 25% of 15-year-olds had used a vape in the past 30 days and 40% had used one in their lifetime.

There was also a gender split - 30% of girls had used one recently compared to 20% for boys.

Only about 11% of the 15-year-olds surveyed were smokers. Health professionals believe vaping is now attracting children who would never have been tempted to try smoking.

Has an invention hailed as a game changer in the battle against tobacco inadvertently created a generation of children addicted to nicotine?

How addictive are vapes?

Some experts consider nicotine to be as addictive as heroin or cocaine., external

It takes just seconds for the nicotine to reach the brain where it triggers the release of dopamine - a chemical linked to feelings of pleasure.

Vaping products come in a range of nicotine strengths but almost all disposables in the UK contain the highest legally allowed amount - 20mg/ml or 2%. Illegal products available online could contain even higher concentrations.

The type of nicotine in single-use vapes is usually nicotine salt-based which has a less harsh "throat hit" than other forms, making these vapes more palatable for children.

Comparisons of the amount of nicotine absorbed though vaping vs smoking is complicated by a number of factors - but Linda Bauld, professor of public health at University of Edinburgh, believes high numbers of young people may now be dependent on nicotine.

"We've been surprised by the high numbers of young people who are now vaping due to product innovation and we need to take proportionate measures to address this," she told BBC News.

Disposable vapes come in various "puff" capacities - but some teenagers are getting through the common 600-puff variety in just a day or two.

Emily Banks, from the Australian National University, a visiting professor at Oxford University's Nuffield Department of Population Health, believes nicotine addiction is in itself a significant harm.

"We have kids who are experiencing addiction who have difficulty sitting through a lesson or sitting through a meal with a family," she told a meeting of the Scottish Parliament's health committee earlier this month.

Are vapes dangerous?

Most health professionals believe nicotine itself is relatively harmless. Lab tests on mice have found some links to cancers and respiratory ailments but there's debate within the scientific community on how much can be drawn from such research.

But there is widely-shared concern about other chemicals used in vapes - particularly the flavourings.

These are mostly substances already used as food additives but there is little research on the long-term effects of inhaling them.

Confiscated vapes at a school in England were found to have high levels of metals

Earlier this year BBC News also found that vapes confiscated from pupils contained unsafe levels of lead, nickel and chromium.

Prof Banks said analysis of some e-cigarettes had found between 900 and 2,000 distinct chemical entities, some of which are already known to be "hazardous".

Illicit vapes are a greater concern. In 2019/20 nearly 70 deaths were recorded across the USA when cannabis products were introduced to refillable e-cigarettes.

Investigations later found vitamin E acetate used in them had caused lung damage.

A head teacher in Oldham recently issued a warning that vaping could kill, after a 12-year-old pupil who had used a vape containing the illegal synthetic drug spice needed hospital treatment.

How hard is it to quit vaping?

Like many drugs, when you stop taking nicotine you can suffer withdrawal symptoms.

Headaches and dizziness could be among the first, though they taper off relatively quickly.

A bigger challenge is cravings as the brain cries out for the dopamine it has become accustomed to.

They could start within 30 minutes of quitting and while each craving typically lasts 15-20 minutes, they just keep coming. As with smoking it takes huge self discipline to resist them.

Other physical symptoms include fatigue, constipation and increased appetite - but there are also mental and emotional challenges.

After a few days without nicotine, many people report a rise in restlessness and anxiety, while others suffer depression.

Irritability is another symptom while brain fog may affect the ability to concentrate for 2-4 weeks as the nicotine wears off and leaves the body.

What can be done about it?

Education is an obvious approach. In November the Scottish government announced a new information campaign and educational materials for schools.

Campaigners argued that peer pressure and a greater inclination to take risks among young people meant that was unlikely to succeed on its own.

UK Health Secretary Victoria Atkins told the BBC she was confident the new bill would pass Parliament by the time of the general election - expected to be this year - with it coming into force in early 2025.

Once the timing is confirmed, retailers will be given six months to implement it.

Some countries have already taken strict measures to restrict use among youngsters.

Denmark have banned flavourings apart from tobacco flavours. China has also outlawed flavours for its own citizens even though it exports most of the world's flavoured disposable vapes.

Australia has gone further by banning all types of vaping device, meaning they are only available on prescription.

These countries have lower vaping rates than the UK - but still significant numbers of young people are vaping, with products easily available on the internet or "under the counter".

While it is illegal to sell vaping devices to anyone under 18 in the UK, it is a hugely profitable trade and enforcement agencies are battling against overwhelming market forces.

Health leaders will also be keen to ensure that the new measures do not make it harder for adult smokers to move to vaping as an alternative.

The latest plans would introduce powers to stop refillable vapes being sold in a flavour marketed at children and to require that they be produced in plainer, less appealing packaging.

The government will also be able to mandate that shops display refillable vapes out of sight of children and away from other products they might buy, like sweets.

Some companies are already going ahead of the law, with one London-based tobacco firm and vape seller backing a ban on sweet or soft drink flavours - though there is evidence that fruit flavours are by far most popular, external among young people.

How do you support a child to quit vaping?

There is currently no national strategy for helping children break free from a nicotine dependency.

Prof Linda Bauld suggests parents seek medical advice, for instance from a GP or an NHS adviser, if their child is struggling to quit.

Only one nicotine replacement product, a mouth spray, is medicinally licensed to help people quit vaping but a doctor can provide more detailed advice on other nicotine products such as nicotine chewing gum or lozenges commonly used to help those giving up tobacco.

Such products should never be used by a child aged under 12, as nicotine is considered toxic for young children.

Some disposable vapes are marketed as "nicotine-free" but tests on some of these products have found that is not true., external The potentially harmful chemicals are still present and the repeated hand-to-mouth action can be a barrier to quitting completely.

In the UK, many health experts believe vaping devices are useful as a less harmful alternative for adult smokers - but some now think the early messaging on the relative safety of vaping may have backfired when it comes to young people.

England's chief medical officer Sir Chris Whitty has put his advice concisely: "If you smoke, vaping is much safer, if you don't smoke, don't vape."

- Published24 May 2023

- Published26 September 2023

- Published12 October 2023

- Published8 September 2023