Sleeping sickness study claims success

- Published

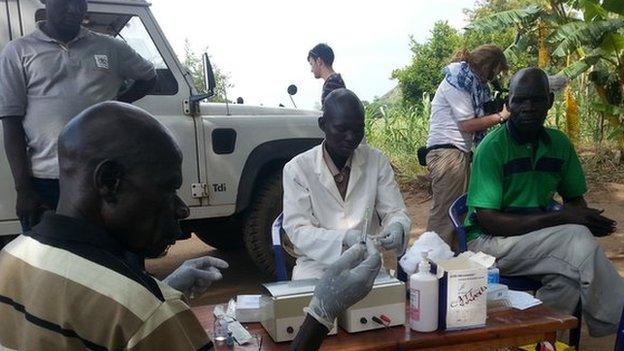

Cattle were injected with a drug to kill the parasite

Researchers from Edinburgh University have claimed thousands of lives may have been saved in Africa by a new initiative to combat sleeping sickness.

The disease, caused by a parasite that attacks the nervous system, is fatal if it is not treated.

Scientists said the number of acute cases in rural Uganda fell by 90% after they injected cattle with a drug that kills a parasite.

The disease is transmitted from cattle to humans by the tsetse fly.

Professor Sue Welburn, the university's vice-principal global access, led the research.

She told BBC Radio's Good Morning Scotland programme that sleeping sickness was a parasitic disease like malaria.

Sleeping sickness is caused by a bite from a tsetse fly which transmits a Trypanosoma parasite

Prof Welburn said: "It is transmitted by tsetse flies and they inoculate these parasites into your blood where they multiply and then these parasites move from your blood to your central nervous system where they cause profound problems and really quite extraordinary symptoms.

"It is absolutely fatal if it is not treated."

She said that domestic cattle had become the main "reservoir of infection" in Uganda.

The cattle do not get sick from the parasite so they can be infected for a long time.

Extremely complex

Prof Welburn said: "It is just a matter of chance that that animal gets bitten by a tsetse fly and that fly bites a human and infects them."

Researchers tested a new approach to sleeping sickness control by targeting 500,000 cows for treatment.

They eliminated the trypanosome parasite that carries the disease by giving livestock a single injection of trypanocide and by carrying out regular insecticide spraying to prevent re-infection.

Prof Welburn said the treatment for humans was extremely complex and expensive but the drug for cattle was "really cheap".

The University of Edinburgh researchers aim to extend the project to all districts of Uganda affected by the condition - treating about 2.7 million head of cattle.

- Published28 June 2015

- Published6 June 2014