Sophia Jex-Blake: The battle to be Scotland's first female doctor

- Published

Edinburgh University was the first in Britain to admit women - but it was a reluctant change. This month marks the anniversary of the first intake in the 1860s and the riot that the reaction to their studies caused a year later.

Sophia Jex-Blake led the women's education charge in Britain, but faced opposition to her aspirations from an early age.

Jex-Blake wanted to be a doctor in a time when it was unthinkable for a woman to be one. She wanted to change that and eventually, she did.

Born in Hastings, she was privately educated and was initially stopped from attending college by her parents.

But determined to pursue her education, a life campaigning for women's rights was apparently destined.

After a period of study in Edinburgh, Jex-Blake travelled to the US in 1865 to learn more about women's education.

Here she met Dr Lucy Sewell, an activist for health and social reform, and resident physician at the New England hospital for women. This meeting, alongside time spent as an assistant at the hospital inspired Jex-Blake to chase her dream of being a doctor.

The fight was just starting.

She was refused entry to Harvard on gender grounds, a rejection letter read: "There is no provision for the education of women in any department of this university."

Resolute, her American quest for education continued, but she was forced to return to England following the death of her father.

With bleak prospects for women's education at home, Jex-Blake looked north to Scotland, where a more enlightened view on education was percolating.

In March 1869 after much internal strain, Edinburgh University approved Jex-Blake's application, but it was eventually rejected by the university court on the grounds the university could not make the necessary arrangements "in the interest of one lady".

Undeterred by her latest setback, a campaign carried in The Scotsman newspaper called on more women to join her. The story gathered attention and more women joined her cause, pushing to study medicine in Edinburgh.

They became known as the Edinburgh seven.

In November 1869, the women passed the matriculation exam and were admitted to the university medical school.

The university charged them higher fees and the women, led by Jex-Blake were forced to arrange lectures for themselves due to a loophole whereby university staff were permitted but not required to teach women. This was just the start of the problems they would face.

Surgeon's Hall riot

Jo Spiller, of Edinburgh University, believes it was a tense time at the university.

"The institution was very divided. The votes on whether to continue with the women students were very close and there are some archival diaries of students who were really horrified about how the women were being treated," she said.

Little more than a year later - tension would turn hostile with the Surgeon's Hall riot on 18 November 1870.

A mob of more than 200 people pelted the women with mud and rubbish as they made their way to sit an anatomy exam. The abuse was unwavering until a supporter hurriedly unbolted a door to get them inside.

Following the incident, Jex-Blake wrote: "On the afternoon of Friday 18th November 1870, we walked to the Surgeon's Hall, where the anatomy examination was to be held. As soon as we reached the Surgeon's Hall we saw a dense mob filling up the road… The crowd was sufficient to stop all the traffic for an hour. We walked up to the gates, which remained open until we came within a yard of them, when they were slammed in our faces by a number of young men."

Ms Spiller added: "This was really the first concerted attempt for women to qualify with degrees from British universities. There was a lot of support but as the weeks and months went on and the women did very well, there started to be a growing opposition to them - a very powerful opposition."

As students sat the exam, the mob shoved a sheep into the hall, causing chaos.

It is said the professor in charge of the exam remarked: "The sheep can stay, it is clearly more intelligent than those out there."

The fracas would become known as the Surgeon's Hall riot and it was the beginning of the end of this chapter of educational equality.

Newspaper coverage swayed public opinion in favour of the women, but at the university discrimination grew, they were denied access to wards and blocked from graduating with degrees.

"Edinburgh became the focus of a national debate - especially after the Surgeon's Hall riot - that became pivotal. Ultimately, it was too much for the university to handle," according to Ms Spiller.

"They struggled on and got all the teaching they needed, but they just couldn't get the university to let them sit the exams they needed. They just ran out of options."

Focus on legislation

Knocked down by the status quo once again, Jex-Blake was undeterred and continued to force change.

The battleground was shifted to London where she continued to campaign, and in 1874, Jex-Blake played an important role in setting up the London School of Medicine for Women.

According to Ms Spiller: "The momentum gained over those four years in Edinburgh became unstoppable."

Aided by Jex-Blake's efforts, the Medical Act followed soon after, allowing the medical licensing of all people, regardless of gender.

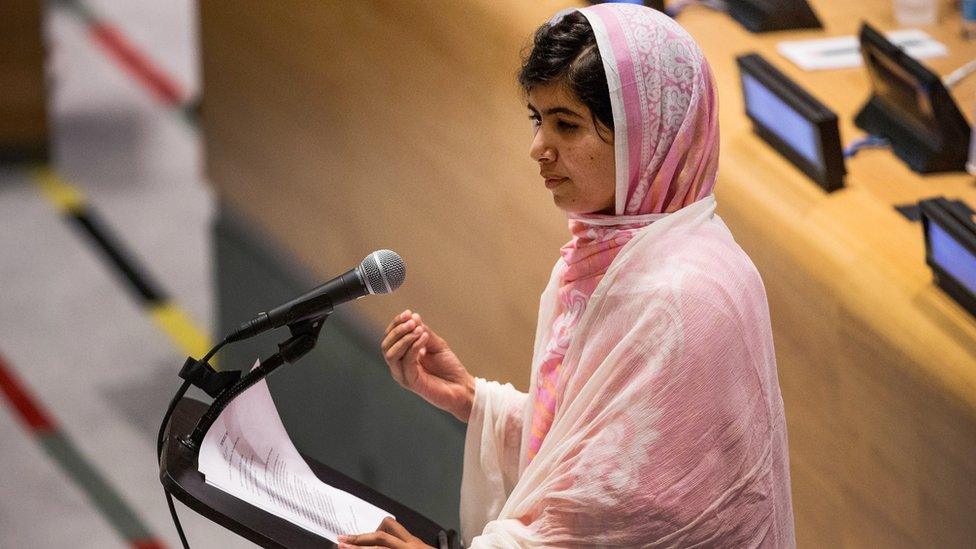

Malala Yousafzai continues to fight for female educational rights having survived a Taliban assassination attempt as a 15 year-old

Jex-Blake finally received her degree when she was awarded an MD in Berne, Switzerland. Many of the Edinburgh seven were forced to Europe to pursue their studies.

Taking advantage of new legislation, she returned to the British Isles and sat exams with the College of Physicians in Dublin, and became one of Britain's first female doctors.

Eventually Jex-Blake returned to Edinburgh - becoming Scotland's first practising female doctor. She went on to found the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women and the Edinburgh Hospital and Dispensary for Women and Children - later Bruntsfield Hospital.

Her political impact also continued as she supported the Enabling Bill, which allowed medical examination boards to have female candidates.

'Fair field'

"Symbolically you can compare Sophia and Malala, fighting for girls' and women's educational rights - the principle of fair field and no favour," added Ms Spiller.

"We can forget that we had these periods of turmoil in our own history - that at one point there was huge resistance to the idea of women going to university and getting a professional education."

"You can't make a complete equivalent, but at the time it was a huge thing she took on."

In the wake of Jex-Blake's path, the University of Edinburgh admitted women to graduate in medicine 1894.

In keeping with her life's work, she had campaigned for women's suffrage until her death in 1912.

She is commemorated by a plaque at the main entrance of the university's medical school building - where women sit in classes that she was chased away from.