'Revolutionary' weld joins glass to metal

- Published

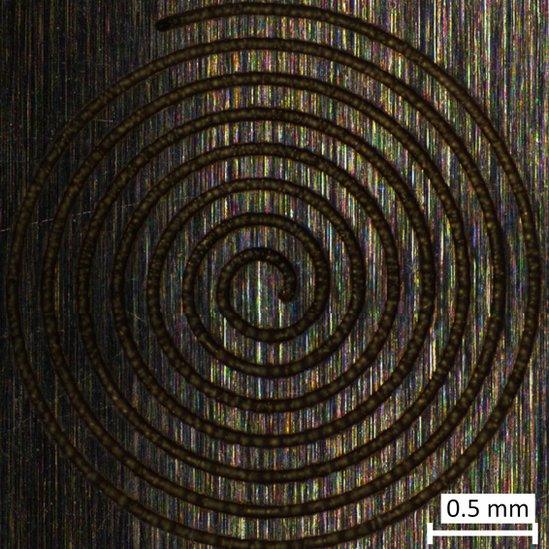

The technique creates intricate welds at a microscopic level

Researchers at Heriot-Watt University have developed a revolutionary new technique to weld glass to metal.

They are using an ultrafast laser system to create tiny "balls of lightning" inside the materials.

They say it could transform the manufacturing sector.

On the face of it, joining glass and metal may not look like too much of a problem.

The issue lies in their very different thermal properties. When heated and cooled they expand and contract at vastly different rates.

If you heat up a piece of metal and melt some glass onto it, the glass will shatter as the metal cools and contracts again.

That is why manufacturers who need a glass-metal bond often use adhesive to get the two to meet.

But glues have their drawbacks. Expansion and contraction of the metal means the glass component can "creep" out of position. The adhesive can also degrade over time.

The theory is deceptively simple

The Heriot-Watt team also use high temperatures, but in a space measured in millionths of a metre.

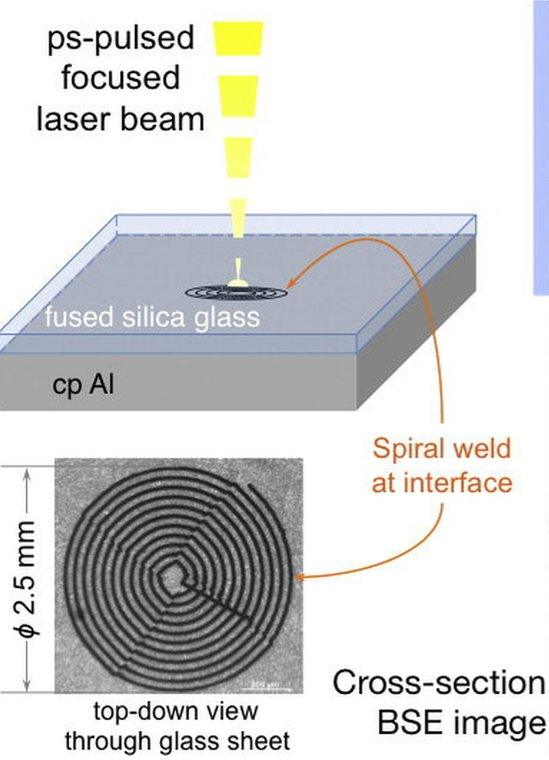

Their technique uses an ultrafast laser to deliver million watt pulses. Each lasts just a trillionth of a second.

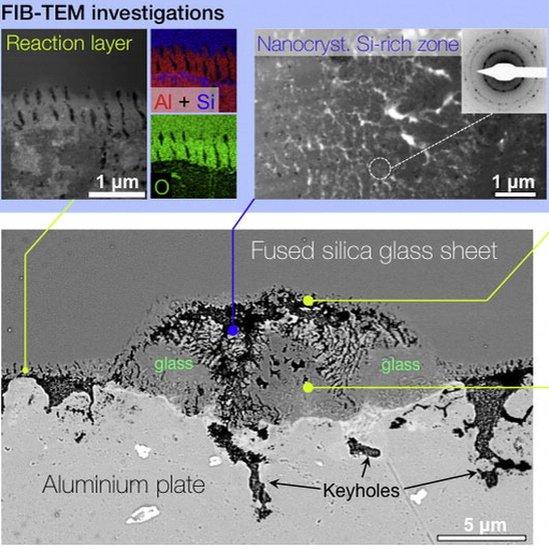

Focusing on the area where glass and metal meet, the laser creates a spot of intense heat that melts both materials.

The scientific term is a microplasma - in effect a tiny ball of lightning inside the material - that fuses the two together.

So far, the team has managed to weld glass, quartz and even sapphire to aluminium, titanium and stainless steel.

Prof Duncan Hand puts the pulses into perspective when he explains that "a picosecond to a second is like a second compared to 30,000 years".

He is director of the EPSRC Centre for Innovative Manufacturing in Laser-based Production Processes, which is based at Heriot-Watt.

A spot of intense heat melts both materials

The centre's everyday handle - CIM-Laser - is a little more user friendly. It also involves Cambridge, Cranfield, Liverpool and Manchester universities.

Prof Hand says: "Being able to weld glass and metals together will be a huge step forward in manufacturing and design flexibility."

The technique could create new products in industries such as aerospace, defence, optics and healthcare.

His team is part of a consortium involving the public and private sectors. The project is funded by Innovate UK, Heriot-Watt and other partners in industry.

Aesthetics are not the point of the exercise, but some images of the welds look like works of art.

One shows a delicate spiral of borosilicate glass neatly fused to a piece of aluminium.

Welds like these will stand the tests of time and temperature.

Prof Hand says: "We tested the welds at -50 C to -90 C and the welds remained intact.

"So we know they are robust enough to cope with extreme conditions."

The prospect of innovative new products means the value of new process is likely to be far greater than the sum of its parts.