Uncovering the men behind the 135-year-old message in a bottle

- Published

Historian Jamie Corstorphine with the bottle - which has been glued back together - and the framed note

The men who left a message in a bottle under floorboards in an Edinburgh house were joiners who helped build the Victorian property - and had 11 children between them.

The 135-year-old time capsule was discovered in November by a plumber who, by chance, opened up the floor at the exact spot where it had been left in 1887.

Since then experts and historians from the genealogy service Findmypast have looked up censuses and pored over dozens of newspaper archives to uncover the story behind the men who left the note - as well as those who lived in the house.

Its inhabitants included the Reverend Archibald Eneas Robertson, who is thought to have been the first mountaineer to climb all 282 Munros.

The two joiners who left the bottle were John Grieve and James Ritchie.

Mr Grieve was born in Leith, and would have been aged 43 at the time. He and his wife Isabella had six children: John, aged 16; James, 11; Bessie, eight; Annie, six; George, four; and Andrew, one.

The family lived on Riddles Close in Edinburgh's historic Old Town, just over half-an-hour's walk from the Morningside property.

Mr Grieve died on 28 September 1906 at the age of 62 after a lingering illness.

Mr Ritchie, 34, who was born in Loanhead in Midlothian, was the second carpenter working on the house.

He lived in the High Street in nearby Liberton with his wife Mary and five children: Rosana, 15, William, 14, James, 12, Mary, six, and six month-old Helen.

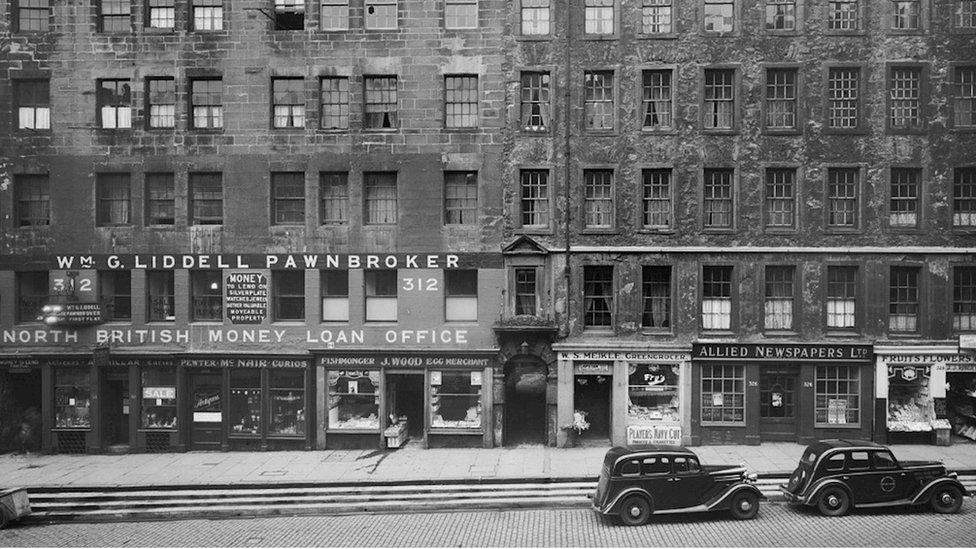

The entrance to Riddles Close in the early 1900s where John Grieve lived with his family

The two men had been working on a row of houses in Morningside when they wrote the note and placed it under the floor in 1887, hidden inside an empty whisky bottle.

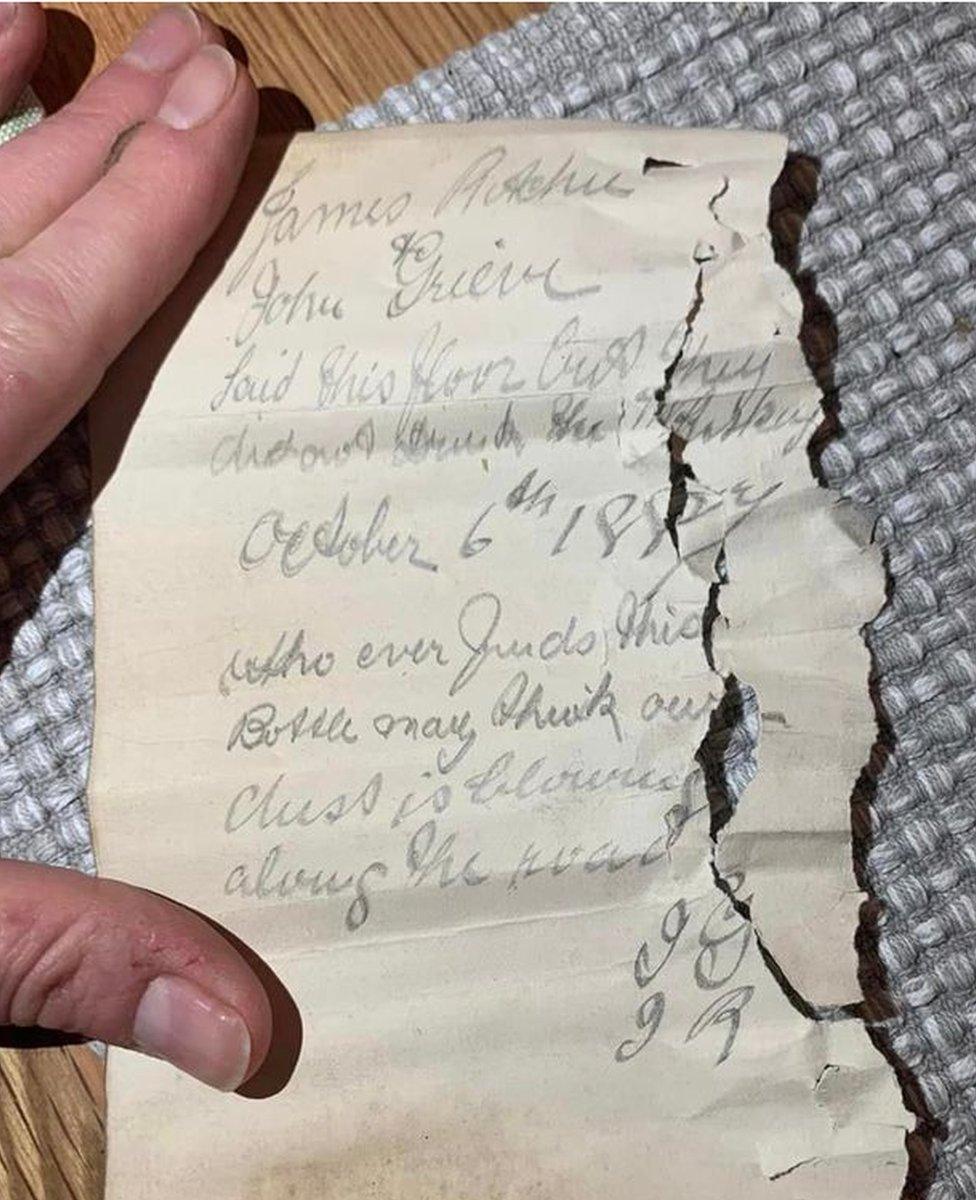

In the note, they said they had laid the floor but did not drink the whisky, adding: "Who ever finds this bottle may think our dust is blowing along the road."

The house was finished and put up for sale in January 1888, before being bought by Robert and Mary Finlayson.

They moved in with their children James, eight; John, seven; and one-year-old twins Mary and Robert.

Robert, 50, was a drysalter, oil and colour merchant. This meant he traded in chemical products, such as dyes and gums, in dried, tinned, or salted foods and edible oils, as well as colourants for in the paint manufacturing trade.

He owned a company called Finlayson & Stuart, in partnership with Harry Jardine Stuart, at Regent Arch in Edinburgh.

It is thought that servants would have lived in the room where the bottle was found

The family were relatively wealthy and well-connected, and were notable enough to appear in the columns of local newspapers - such as when they had a summer visit in 1892 to Bonnington House.

In 1891, two female servants were also living at the house. They were Lizzie Reid, a nurse who looked after the young twins, and Kate Ruffell, for general domestic duties.

Experts believe the bottle was found under a servant's room, which would have belonged to one or both of these women.

Lizzie was born in Burntisland, Fife, in 1869 and would have been 22 at the time of moving into the house.

She grew up for at least part of her childhood with her grandparents James and Jane Reid in Fife.

What else was happening in 1887?

Queen Victoria was monarch, and the year marked her Golden Jubilee, which was celebrated in June.

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil was Prime Minister heading up a Conservative government.

On the same day as the note was written, Hovis first patented their process for the manufacture of breadmaking flour.

The period saw huge advances in science and technology, including the first use of electric light in a home just six years earlier in 1881.

In 1880, education became compulsory for children under 10 and in 1883 married women obtained the right to acquire their own property.

Kate was born in Greenwich, London in 1870 and was 21. She was the youngest of five daughters of James Ruffell, a candlemaker and his wife Jane.

It is thought likely that Kate moved to Edinburgh to work for the family.

Robert Finlayson died at the age of 52 in about 1893, only a few years after moving into the house. It is not known what caused his death.

His business was dissolved and by 1901, Mary and her four children had moved to another property in Edinburgh.

Thomas H B Black, a life assurances company official, and his wife Emily then moved into the house with their three children.

The house was bought in 1912 by the Grant family, before the Reverend Archibald Eneas Robertson moved in with his second wife, Winifred, in the 1940s.

The note is signed and dated by the two joiners who laid the floor

Robertson, who was born in 1870, was a Church of Scotland minister. He first moved to Edinburgh in 1918 as chaplain of Astley Ainslie Hospital.

He is thought to be the first to have climbed all 282 Munros, the Scottish peaks of more than 3,000 feet.

The peaks were charted by Sir Hugh Munro, but Robertson climbed them all between 1889 and 1901.

On completing his final climb, Meall Dearg, he is said to have first kissed the cairn, then his wife.

The couple sold the house in the 1950s.

Jen Baldwin, Findmypast family history expert, said it had been "a fascinating case of voices reaching out to us from the past".

"I like to think that they (carpenters John Grieve and James Ritchie) celebrated laying the final floorboard with a bottle of whisky and philosophising about a time when their 'dust is blowing along the road'."

Peter Allan, a plumber, cut around the bottle without knowing it was there

Local historian Jamie Corstorphine said: "To have an insight into past lives on this level of ordinary people is invaluable.

"To think we now know of all the children and people who walked across this floor above the bottle and all the memories that were made in this house is incredible.

"I wonder if they thought at the time they would be remembered along with gentry who were making appearances in the local press, immortalised by a small message in a whisky bottle."

Eilidh Stimpson, who is the current owner of the house, said: "It's really lovely to hear the history behind the note.

"This has brought the history of my house to life and I can't believe we even now know the names of all the occupants and the children of the joiners."

She had to smash open the bottle to read the note, but has now glued it back together and framed the note.

- Published19 November 2022