Fracking regulations too strict, say Glasgow academics

- Published

Demonstrations have been held across the UK against proposals for fracking

Leading energy engineers from Glasgow University have called for regulations on fracking to be relaxed.

In a new report, two academics said current limits on vibration are so strict that if applied elsewhere they would prevent buses driving past homes.

They also said the risks of serious earthquakes were lower than feared.

But critics said any relaxation would be deeply unpopular, and would suggest that shale gas firms' interests were being put ahead of local communities.

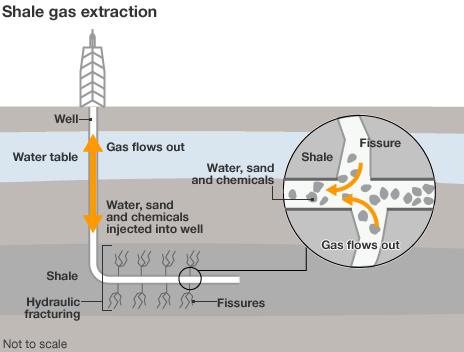

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a technique designed to recover gas and oil from shale rock.

It involves drilling down into the earth before a high-pressure water mixture is directed at the rock to release the gas or oil inside.

The paper, for the Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology, external, called for new rules, closer to those for activities such as quarry blasting.

Its authors, Dr Rob Westaway and Prof Paul Younger from the university's School of Engineering, said the current rules governing fracking in Britain are too strict.

Dr Westaway said: "Currently, the Department of Energy and Climate Change's regulation is that any fracking operation which induces surface vibrations greater than magnitude 0.5 on the Richter scale should be shut down immediately.

"That level of vibration is extremely low. To put it in perspective, if regulations for other vibration-causing activities were similarly restrictive you'd have to prevent buses from driving in built-up areas or outlaw slamming wooden doors.

"By analysing the seismic waves which travel through the earth as a result of fracking activity, we've been able to determine a scale of activity which will create surface vibrations within those already allowed for by quarry blasting regulations."

'Nuisance vibration'

Dr Westaway said that "induced earthquakes of magnitude 3 from fracking activities 2.5km below the earth's surface "would "create surface vibrations similar to the limits allowable from quarry blasting".

He added: "Conversely, induced earthquakes at the current UK regulatory limit of magnitude 0.5 would be expected to produce vibrations in a person's home that are smaller than those typically caused by the movement of buses or lorries past the end of their garden and comparable to many other widely-accepted forms of 'nuisance' vibration."

Both academics said that the largest possible fracture which could be created by current drilling processes would be 600m long.

Prof Younger added: "We've determined that a fracture of that length created in a single rupture, which is very unlikely, would likely correspond to a maximum quake of magnitude 3.6.

"That might be sufficient to cause minor damage on the surface such as cracked plaster.

"Again, however, there is already regulation in place for compensation for similar incidents caused by RAF fly-bys or mining operations and we'd suggest it would make sense for similar schemes to be put into place for fracking."

Prof Young said "the biggest cause of serious seismic incidents" was not the drilling or fracking process, but "the practice of disposing of waste water back into the borehole once the process is finished".

Shock waves

He said: "This washes away particles of sand holding open the fractures created during the process, which can cause earthquakes.

"In Britain, we've adopted longstanding EU groundwater regulations which bar subsurface disposal of wastewater completely, meaning there is no danger of this sort of event happening here. Instead, the water would be treated and disposed of safely elsewhere."

However, critics of fracking challenged the report's findings.

Tony Bosworth, an energy campaigner from Friends of the Earth, said that the current regulations were in place for a reason, citing the example of the Preese Hall-1 well, near Blackpool.

In 2011, a report, external carried out by independent experts for the energy firm Cuadrilla found that it was "highly probable" that shale gas test drilling had triggered earth tremors in the area.

"Any move to weaken safety rules on fracking will send shock waves around local communities who face the threat of shale gas extraction under their homes," he said.

"Further watering-down of regulations... would be deeply unpopular and show that the government is putting the interests of shale gas firms ahead of people."

- Published15 August 2014

- Published30 June 2014

- Published13 December 2012