Margaret Fleming: The teenager who was forgotten for 17 years

- Published

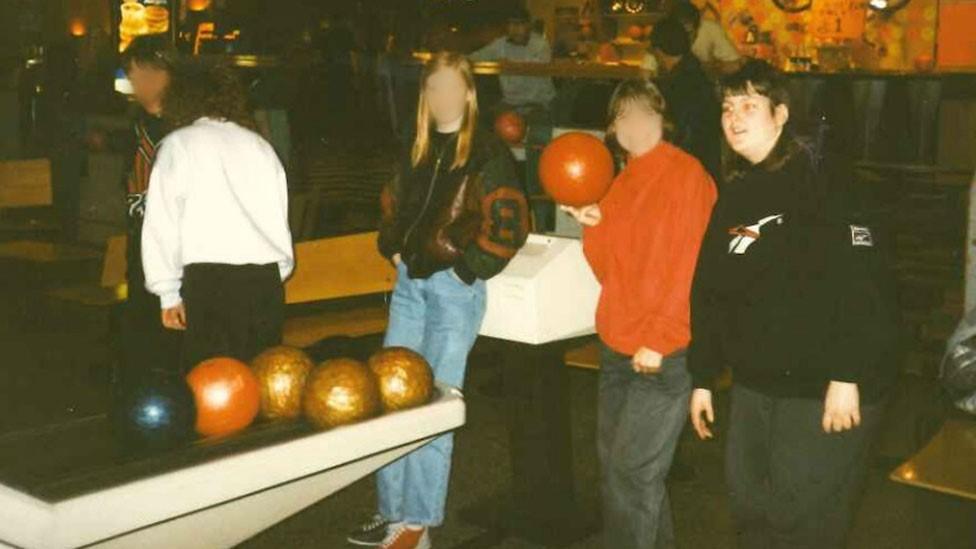

Margaret Fleming pictured on a college night out

Margaret Fleming was a vulnerable young woman who vanished without trace - and no-one raised the alarm for almost 17 years.

She was 19 years old when she was last seen by anyone other than Edward Cairney and Avril Jones.

Her disappearance was so mysterious that at one point police asked the couple, who were meant to be Margaret's carers, if she even existed.

Their version of her life was stranger than fiction.

The wild claims made by Margaret Fleming's killers

They claimed that Margaret, who had learning difficulties, ran off with a traveller, then went on to become a gangmaster who travelled Europe, and a drug dealer with several aliases.

Precisely what happened may never be known, but a jury found the pair guilty of murdering Margaret within three weeks of that final sighting on 17 December 1999. Her body has never been found.

During the seven-week trial, the prosecution painted a bleak picture of Margaret's life before she disappeared.

Early challenges

An only child, she was brought up in the town of Port Glasgow, Inverclyde, and faced challenges from an early age.

At Slaemuir Primary School, Margaret struggled with reading and writing, and she continued to require additional support as a pupil at Port Glasgow High.

But two defining events ultimately led her into the care of her killers.

Margaret was described as a quiet figure at school

In January 1993, her parents Derek and Margaret divorced after 20 years of marriage.

The schoolgirl was 12 when she left the family home to move in with her father and grandparents.

The jury heard Margaret had a bad temper and was described by her mother as difficult to handle.

In contrast, she was a quiet figure in the classroom and required constant encouragement.

A rare letter of praise

In a 1995 report, teacher Elizabeth Brown wrote: "Margaret Fleming has moderate learning difficulties. She works fairly well to her ability but needs written instructions set out simply and gone over verbally."

In evidence she said: "If you left Margaret on her own she would do very little. You had to prod her to do the work. Her marks were all at the very bottom end of the school."

On one rare occasion another teacher put on record her gratitude to the teenager for helping her with registration.

Margaret Fleming pictured with Avril Jones

This provided one of the most poignant moments of the trial at the High Court in Glasgow.

Ms Brown recalled: "She clearly thought Margaret deserved a letter of praise, which Margaret wouldn't have got many of during her schooling."

Another retired teacher, Elaine Moore, said: "She was quite isolated. Her and her dad were a wee unit. She was concerned about him and he was concerned about her."

Mr Fleming, a tradesman who retrained as a lawyer, was so protective of his daughter he didn't tell her why he had been taken in to hospital. He had been diagnosed with terminal cancer.

'A rather lonely, isolated girl'

His condition had deteriorated by 20 October 1995, when his ex-wife took Margaret to Inverclyde Council's social work office.

The meeting was arranged to discuss her behavioural problems, which included arguing with her grandparents.

The referral said: "Margaret does not know why her father is in hospital and is afraid it is something serious."

Margaret with Cairney and Jones

It also noted the child was always with her father and felt "rejected" by her mother.

The report continued: "I feel like Margaret is a rather lonely, isolated girl who is living with elderly grandparents.

"Margaret appears to be surrounded by a great deal of uncertainty and ill health."

Five days after the meeting, Mr Fleming lost his battle with cancer.

His death not only devastated Margaret but proved to be the catalyst for her eventual move from Port Glasgow to Inverkip, 10 miles along the Clyde coast.

The couple's Seacroft home sits on the banks of the Firth of Clyde

Mr Fleming thought that his parents were too old to take care of his daughter.

He had earlier told his fiancée Jean McSherry that if anything happened to him, Eddie and Avril would look after Margaret.

During the trial Margaret's mother, 71-year-old Margaret Cruickshanks, recalled how she first met Cairney.

She said: "After Derek died they were at the funeral. Eddie Cairney came and approached me and said if I needed any help with Margaret he would give me respite care."

Eddie Cairney had offered to help with respite for Margaret

The court heard Margaret initially lived with her mother but later spent up to a fortnight at a time staying with Cairney and Jones at their dilapidated home, which was named Seacroft.

Ms Cruickshanks said her daughter was even more difficult to cope with after the loss of her father.

She added: "She would come back from school and I'd say: 'What were you doing?'

"Her temper would be up and she would batter me."

A strained relationship

A month after Mr Fleming's death, Margaret and her mother met Inverclyde Council social worker Denise Munro in a bid to secure support from the additional needs team.

Ms Munro recalled: "She was quite a naïve girl, quite vulnerable, quiet, lonely, sad and did not have many friends."

She said there had been a strained relationship between mother and daughter.

Giving evidence, she added: "When I went to their house to pick up Margaret I would have a conversation with her mum, who found it difficult.

"She had lived on her own and had an adolescent girl who was missing her dad."

The back garden of Seacroft, where Margaret lived with Cairney and Jones

Ms Munro continued to support the teenager until she went on maternity leave in July 1996.

By this time, Margaret had enrolled on a skills for life course at James Watt College in Greenock and appeared to have settled down.

But that August, Ms Cruickshanks told the social work department that her daughter's behaviour had deteriorated.

But she received no further support and no-one stepped into Ms Munro's role.

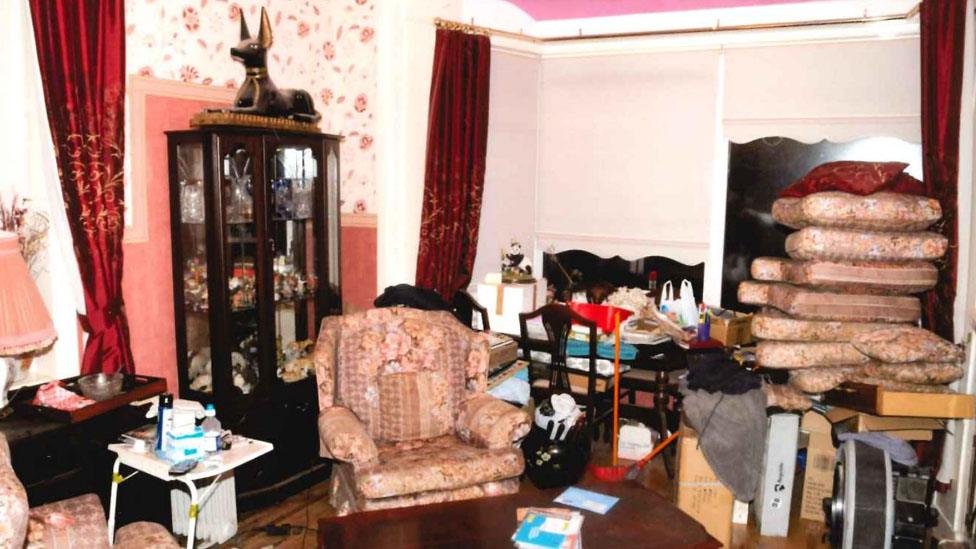

The living room of the house in Inverkip

All ties between mother and daughter were finally severed after a chilling confrontation on 26 November, 1997.

Ms Cruickshanks told the jury she was attacked by Cairney after travelling to Inverkip to tell him she wanted her daughter to come home.

She said Margaret, who struggled with her weight, was then brought downstairs from her attic bedroom and asked where she wanted to live.

Ms Cruickshanks said: "I think she was a bit nervous and she turned round and said she wanted to stay there. There was nothing I could do about it."

She later called the police who went to check on Margaret.

'I didn't visit any more'

Memories of that night reduced her to tears in the witness box as she recalled: "The police came back to say she was alright. As far as I knew that was where she was living.

"I didn't visit any more. I got a letter. It said she didn't want to see me any more."

In the months that followed, Margaret became more reclusive and Cairney told the jury he tried to stop the teenager self-harming by putting cardboard tubes on her arms.

In October 1999, Margaret saw her GP, Dr James Farrell, for the last time.

He told the court she had "quite significant learning difficulties" and said she might have had Sotos syndrome, external from birth - although a definitive diagnosis of the rare disorder was never made.

The GP also said she was "socially and educationally" isolated and referred her to a psychologist.

Dr Alan Smith visited Seacroft before Christmas but all attempts to contact Margaret to arrange another appointment came to nothing.

Last confirmed sighting

The three-week timeframe during which detectives believe Margaret was murdered was narrowed down by the testimony of Avril Jones' brother, Richard, and mother, Florence.

The last confirmed sighting of Margaret was at Richard Jones' new home in Inverkip on 17 December 1999.

Florence Jones remembered Margaret as a "very, very quiet girl" who was unable to look after herself due to her learning difficulties.

The 79-year-old played a key role in the chronology of the case.

The last known photograph of Margaret was taken in March 1999

Her most recent memory of Margaret was at her ruby wedding celebrations in March 1999, and a photograph from that night is the last known image of the teenager.

Crucially, Mrs Jones had no recollection of Margaret joining the family at Mr Jones' house for Christmas dinner in 1999.

There was also no sign of her in the photos taken that day.

On 5 January, 2000 Mrs Jones spoke to her daughter on the phone.

The pensioner told the court: "She said Margaret had left with a traveller. I wasn't sure what had happened. It was up to them."

As the months turned to years, memories faded and not one person saw fit to report that a teenage girl had simply disappeared off the face of the earth.

Indeed it was not until October 2016 that a missed appointment for a benefits review finally led police to Seacroft.

Covering their tracks

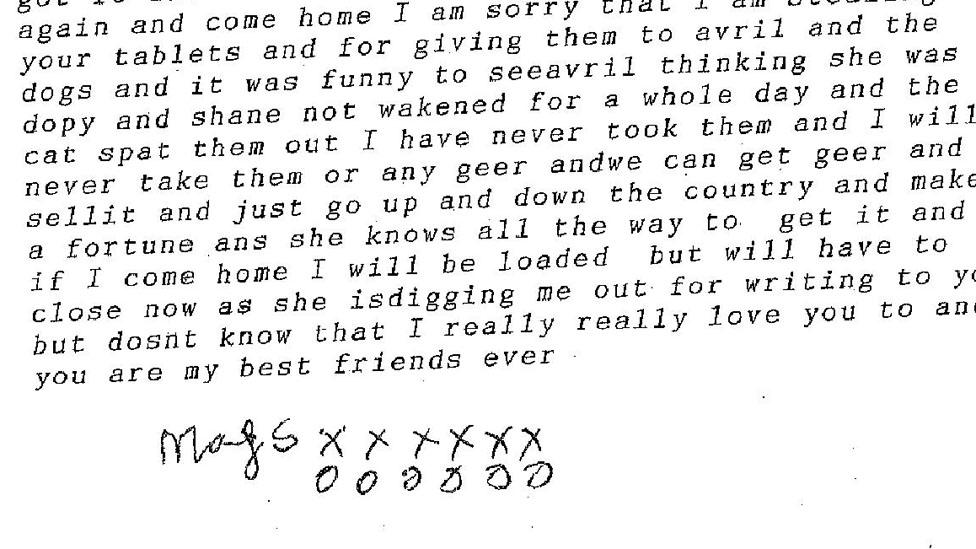

The couple produced letters which they claimed had been written by Margaret

The couple's attempts to cover their tracks, while Avril Jones fraudulently claimed £182,000 in benefits, included producing letters which were said to be from Margaret.

One was said to be from Carlisle on 9 January 2000 and the other two were from the Regent Palace Hotel in Piccadilly Circus, London, on 13 January, 2000.

As part of the complex investigation that followed detectives showed the typed letters to Jacqueline Cahill, who taught Margaret standard grade English at Port Glasgow High between 1994 and 1996.

She told the court the teenager would not have been capable of writing them.

Ms Cahill said: "She had literacy difficulties.

"She struggled to put pen to paper. She struggled to read, and read at about the level of an eight-year-old."

Jacqueline Cahill recalls her memories of Margaret Fleming

But despite her struggles in the classroom, the teacher told BBC Scotland Margaret had the potential to hold down a job that did not require some numeracy and literacy skills.

She added: "If she had stayed in Port Glasgow, she would have stayed in touch with her friends, but moving to Inverkip probably made it easier for Margaret to slip off the radar.

"I don't even want to imagine what her life was like when she was living in Inverkip."

'This wee girl was forgotten'

The teenager's life and death has had a profound impact on Ms Cahill.

She said: "There isn't anyone who remembers Margaret.

"I taught her for two years and I am here speaking about her as a person and I am one of the only people who remembers her.

"That is one of the saddest things that this wee girl was forgotten - abandoned with supposed carers, and forgotten about for 20 years."

Watch Now on BBC iPlayer: Murder Trial: The disappearance of Margaret Fleming