Grace Handling death: 'Not proven verdict messes with your mind'

- Published

Grace Handling was found dead at a house in Irvine, Ayrshire, in 2018 after taking ecstasy

A father whose 13-year-old daughter died after taking ecstasy has welcomed moves to abolish Scotland's "not proven" verdict in criminal trials.

The man who admitted he had given her the pills, was acquitted of killing the schoolgirl after the "not proven" verdict was reached.

Her father Stewart Handling told BBC Scotland it had left him a broken man and messes with his mind.

But he said was he was encouraged that the Scottish government was listening.

The changes are part of a planned new Criminal Justice Bill.

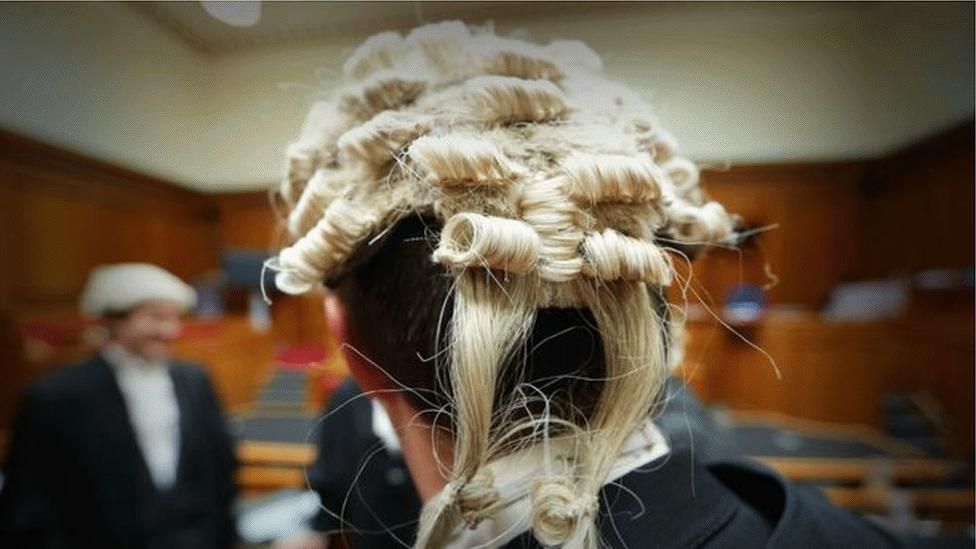

Scotland, unlike most of the world's legal systems, has three possible verdicts in criminal cases - guilty, not guilty and not proven.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said that scrapping not proven was "firmly intended" to improve access to justice for victims of crime.

Mr Handling, who has campaigned for an end to the three-verdict model, said he was shocked when he heard that the changes were part of the new Bill.

"It was a shock in a good way," he said. "I didn't expect it as quick as this - I know how slow politics is.

"I was blown away by the Scottish government. They are being very democratic because over 62% of the consultation on not proven was in favour of a change."

Stewart Handling said he was a broken man after his daughter's death

Mr Handling said his daughter's death and the way it was dealt with by the courts still impacted the family.

"It kills you inside - I am a broken man," he said. "I just put a face on the world but I am devastated still, four years on.

"But I have to carry on for my other kids, and my wife and my family but I will never be the same person again, neither will my wife, or my daughter or my son."

Grace, a pupil at Irvine Royal Academy, was found dead at a house in the Ayrshire town in 2018 after taking ecstasy from a teenager, then aged 17, she had met three weeks earlier.

He said he was encouraged and felt that the Scottish government was listening to the families affected by not proven verdicts.

"Not proven is a convenient route for [the jury], it's like a vote for a politician to abstain," Mr Handling added.

"It doesn't address the crime and it doesn't help the victims, it just helps the jury members come to a decision."

He added: "It leaves you hanging in the air, because you know you were so close to a decision.

Miscarriages of justice

"I am two years down the line from the trial and my mental health is still struggling. Not proven messes with your mind."

The move has been criticised by some in legal circles who argued that the verdict offers additional protection to the accused, ensuring they will not be convicted if a jury has doubts.

Legal defence specialist Thomas Ross QC told BBC Radio Scotland that the changes were likely to go through but could lead to more miscarriages of justice.

"The not proven verdict is only one feature of the legal system in Scotland," Mr Ross said. "If it is removed, they will have to amend the majority system - if they follow the English system, the Crown would require to persuade 12 of the 15 jurors before there can be a conviction.

"It does provide a safeguard. Ultimately the question for a jury is, has it been proved beyond reasonable doubt or not.

"Not proven makes perfect sense to people who sit in court every day and watch the way juries operate."

"I think it's important for people who work in the system, and see people who are the victims of a miscarriage of justice every day of the week, to educate people and make it clear that messing about in an uninformed way with one particular aspect of the trial process is likely to result in more injustices."

- Published6 September 2022

- Published18 September 2020

- Published11 September 2020