Ferguson Marine: Scotland's long-delayed ferry 'is coming to life'

- Published

David Tydeman has been at the helm of Ferguson Marine since February last year

Standing at the helm of Glen Sannox, David Tydeman has the relieved look of a man coming to the end of a long and difficult journey.

After eight years of construction, the boss of Ferguson Marine shipyard in Port Glasgow is so confident the ship at the centre of Scotland's ferries fiasco is nearly ready that he has invited the cameras inside.

Cables snake everywhere, insulation glints in the sunlight, ceiling panels have yet to be fitted and protective coverings mask the floors - but the hard work is done.

"The ship is coming to life," he declares.

Many of the power and control systems on board Glen Sannox are now operational

Entering the wheelhouse of Glen Sannox feels a bit like stepping onto the bridge of the Starship Enterprise.

Control panels are packed full of high-tech equipment. The ship's wheel looks more like something you would expect to find on a Ferrari rather than a passenger ferry.

At either side are the port and starboard wing control units offering complete control of the ship while manoeuvring into harbour. A glass floor panel allows the officers to see precisely how close they are to the quay.

"Everything is working. You could take this ship down the river," he tells us. "We haven't got our final certificates yet so it wouldn't be legal but operationally, rudders are working, the steering gear is working, we can run the ship from here."

The wing control units allow complete control of the ship while manoeuvring at the quayside

Glen Sannox and its sister vessel, Hull 802, have become some of Scotland's best known ships - for all the wrong reasons.

Six years late and three times over budget, many have wondered if they would ever leave the yard at all. There are children completing their second year of primary school in Port Glasgow who have lived their entire lives with these ships a seemingly permanent part of the landscape.

So why have they proved so hard to build?

If you ask the customer - government-owned ferry procurement agency CMAL - it will say it was due to "catastrophic contractor failure", external by FMEL, the company owned by businessman Jim McColl who rescued the yard from administration in 2014.

CMAL says McColl's managers pressed ahead with fabrication without a proper design (despite it being a "design and build" contract) and ended up "chasing steel" to trigger milestone payments as cashflow problems mounted.

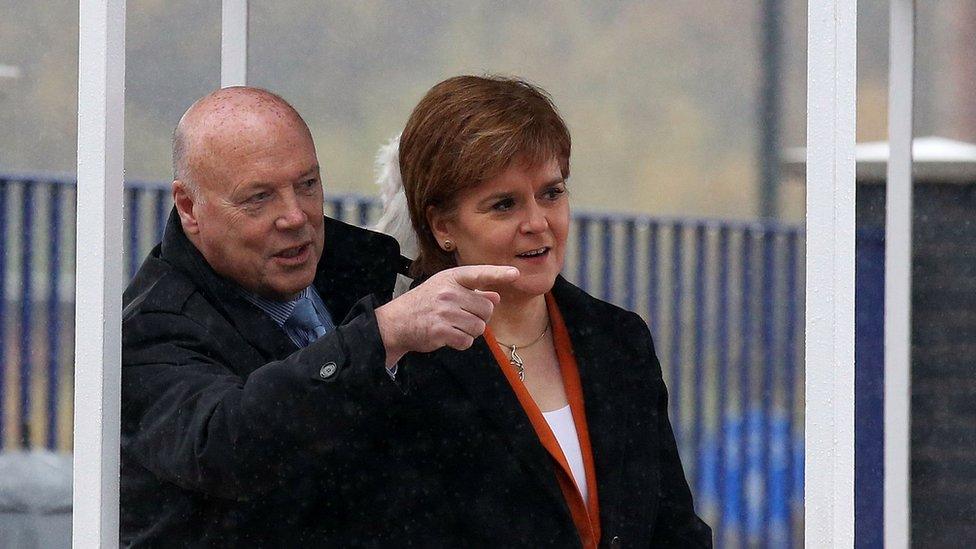

Nicola Sturgeon joined Jim McColl for the slipway launch of Glen Sannox in November 2017 - but the hull was largely empty

For his part, Jim McColl claims he was handed a "poisoned chalice" by CMAL who messed up the basic specifications and concept design (which was CMAL's responsibility) - then frustrated his team by constant interference and requests for changes.

That's a view shared, at least in part, by Commodore Luke Van Beek, a procurement expert appointed when Humza Yousaf was transport minister, who told MSPs, external: "If you are going to put in place a design and build contract, you should have the specification almost complete when you let the contract. That was not what happened."

Wisely, Mr Tydeman avoids being drawn into the blame game.

And having only started in the job 16 months ago, he does not have to own the mistakes that have created what many regard as the biggest public procurement disaster of the devolution era.

According to some estimates, external the combined cost to the taxpayer of the ships and supporting the shipyard is close to half a billion pounds.

But he does believe the problems started very early on. "I think the build strategy adopted in 2015, when we all look back in hindsight, was unwise, it embedded costs," he says.

"It was partly because the design wasn't finalised and I gather there were a lot of conversations going on between CMAL and FMEL about finalising the design.

"It's easy to look back and be critical, but the decision to build an empty ship and put things in later is unconventional and has added cost."

The Ferguson Marine boss explains to the BBC's David Henderson why Glen Sannox has taken so long to build

To illustrate his point, he gestures to the ceiling, which is crammed with cables.

"All the brackets, all the racks that hold things could have been done while this was upside down in the shed as a module. Instead this had to be done on ladders, on scaffolding, working in the ceiling."

More expense has been incurred correcting mistakes made both before and after the yard was nationalised in 2019 when FMEL went bust.

"It doesn't matter if you're building a kitchen, building a skyscraper or building a ship. It's the same basic things. Is the design complete? Have you got the specification? Have you got the right plan to do it in the right sequence?"

Unlike the four CalMac ferries currently being built in Turkey, Glen Sannox has the added complexity of a dual-fuel propulsion system which can use both conventional marine gas oil (MGO) which is similar to diesel or liquefied natural gas (LNG)

That LNG has to be stored at minus 160-170C in a huge tank in the belly of the ship, and moved around in cryogenic pipes. The ship contains 300km (186 miles) of cabling and 12,500 pipe sections.

David Tydeman says Glen Sannox is a sophisticated ship but the yard now has the skillset to deliver such vessels

"One of the problems with a car ferry is that you have to squeeze all your systems below and around the car deck. So you pack in your engineering, your systems, your pipework into confined spaces and that makes it complicated."

Barring any final surprises, Glen Sannox should be handed over to CMAL by the end of this year, although it is likely to be next spring before the ship is finally deployed on CalMac's busy Arran route.

"I think she's going to be a great ship. As we walk around you see the quality of the passenger areas, there's catering for 1,000 people on board. There's good capacity for car carrying and lorries. I think she'll be a pleasant surprise," he predicts.

A short distance away, encased on scaffolding on the slipway, work continues on an identical ship still known only as Hull 802.

Last month, in a jaw dropping moment at Holyrood, cabinet secretary Neil Gray told MSPs it would be cheaper to scrap the ship and place a new order with an overseas shipyard.

David Tydeman appears slightly baffled by the figures used to make that calculation - but he is sure the government's decision to continue funding the build in Port Glasgow is the right one.

David Tydeman says ministers made the right decision by continuing to fund the build of 802

"If ministers or CMAL decided to order a ship from Turkey, you'd have to wait many years to get another ship. This is going to be a good ship, and I think it was the right decision."

The high cost of finishing 802, as with Glen Sannox, is largely due to the way the ship's steelwork was fabricated without components pre-fitted. While it's too late to change that, there are lessons to be learned.

"We've been very careful on 802 to plan the learning from this ship - capture it, clean up the design drawings, make sure that before we start putting things inside 802 we've captured all the learning from 801."

The wheelhouse was lifted onto Hull 802 on Monday

Monday was a big day for the shipyard and 802 as the pre-fabricated aluminium wheelhouse was lifted onto the deck.

It's the final major piece of fabrication. All the fitting out work will take place on board - and for the welders based in the module hall, their work on the ferries is done.

So what is the future for Ferguson shipyard?

On the day he shows us around, David Tydeman is clearly excited about a lattice of steel that has been been constructed in the main fabrication building.

The past and the future - the wheelhouse of 802 and the first "reference table" ready for accurate construction of Type 26 frigate modules

This is a "reference table", he explains - a solid raised base that allows structures to be welded together accurately without distortion. Two more are planned.

They are to be used for the construction of three units for a Royal Navy Type 26 frigate, work that has been subcontracted by BAE Systems which is building the warships at the Govan yard 15 miles up river.

While a relatively small project, enough to keep Ferguson's welders in work until the autumn, he seems confident it will lead to much bigger subcontracting orders - hopefully whole bow sections for five more Type 26 frigates.

"To put it in perspective, a bow block on a warship is about a third of the size of 802," he says.

The same reference tables could be used to construct seven new "Loch class" small vessels for CalMac - a contract the yard will bid for. These all-electric ships are similar to MV Hallaig, MV Lochinvar and MV Catriona which the yard built on budget and on time a decade or so ago.

More order potential exists in building support vessels for the burgeoning offshore wind farm market. The yard is currently in discussions with two operators who are keen to build ships in Scotland.

So can a Scottish shipyard really compete in the open market with rivals in Poland, Romania or Turkey where labour costs are so much less?

There's more investment needed in productivity, he concedes. A new plating line, burning tables and better computer software to pull the systems together are on his shopping list.

Third year trainee welders Ross McGeown, Mackenzie Miller and Jason Madden are among 52 apprentices at the yard, which has 320 people on its payroll

But many of the costs of building a ship, the engines and other equipment, are the same for shipyards both at home or abroad, he argues. The extra cost of building in Scotland, with better rates of pay, is manageable and "worth the social premium of keeping jobs in the UK".

The yard currently has 320 directly employed staff, 52 of them apprentices. When it recently advertised for a new intake of 15 apprentices it received 500 applications.

This year the shipyard marks its 120th anniversary. The current boss is keen for it be judged on that history rather than the unique circumstances surrounding hulls 801 and 802.

"I started my career 40 years ago in the Govan shipyards. The shipbuilding market in the world and in the UK particularly is the most buoyant I've seen in 40 years. There's a great opportunity for this yard to have good future 10 or 20 years ahead," he says.

There was a time when signs for the Ferguson shipyard signs had the words "Proud Shipbuilders" emblazoned on them. David Tydeman is hopeful those days are coming again.

- Published6 June 2023

- Published23 March 2022

- Published27 September 2022

- Published27 September 2022