Poor Things: 'I don't mind they erased Glasgow from dad's book'

- Published

Actress Emma Stone plays Bella Baxter in Poor Things

The film Poor Things has already won awards and been tipped for Oscar success despite only opening in cinemas around the UK this weekend.

Based on a 1992 novel by Scots artist and writer Alasdair Gray, it's the fantastical tale of a woman who takes her own life and is revived by a Victorian surgeon who replaces her brain with that of her unborn child.

Filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos was blown away by the book which he first read in 2009.

"I completely fell in love with Bella Baxter - and it was obvious to me that somehow I had to bring her to life.

"I was surprised no one had made a film version."

In fact, there was a film version - written by Alasdair Gray and Sandy Johnson - just two years after the book was published. They envisaged a cast which included Robert Carlisle and Helena Bonham Carter but it was a project which didn't get off the ground.

Lanthimos travelled to Glasgow in 2011 to meet Alasdair Gray, and was taken on a tour of the places mentioned in the book. A year later, Lanthimos acquired the film rights.

A decade later, with a screenplay by Tony McNamara, the film began shooting on a set in Hungary, the Glasgow locations replaced with futuristic versions of Paris, Lisbon and London.

Original setting Glasgow was shunned for futuristic versions of Paris, Lisbon and London

It has led to a frenzied debate on social media about whether the loss of the location has lessened the film.

But Alasdair Gray's son Andrew, who looks after the Gray estate, disagrees. He believes the production and its entire cast and crew treated the book with respect.

"When I met the cast, a lot of people had read the book so I was very impressed with that.

"My father didn't set any pre-conditions when he met Yorgos. The contract was drawn up, probably around 2012 and he was aware and in agreement with the circumstances of it.

"He wasn't a film director. He was happy for someone else to take on his work."

Filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos (far left) with the Poor Things cast - Emma Stone, Willem Dafoe, Mark Ruffalo and Ramy Youssef at the 81st Annual Golden Globe Awards

There's also more than a hint of Gray in the character of Baxter, played by Willem Dafoe.

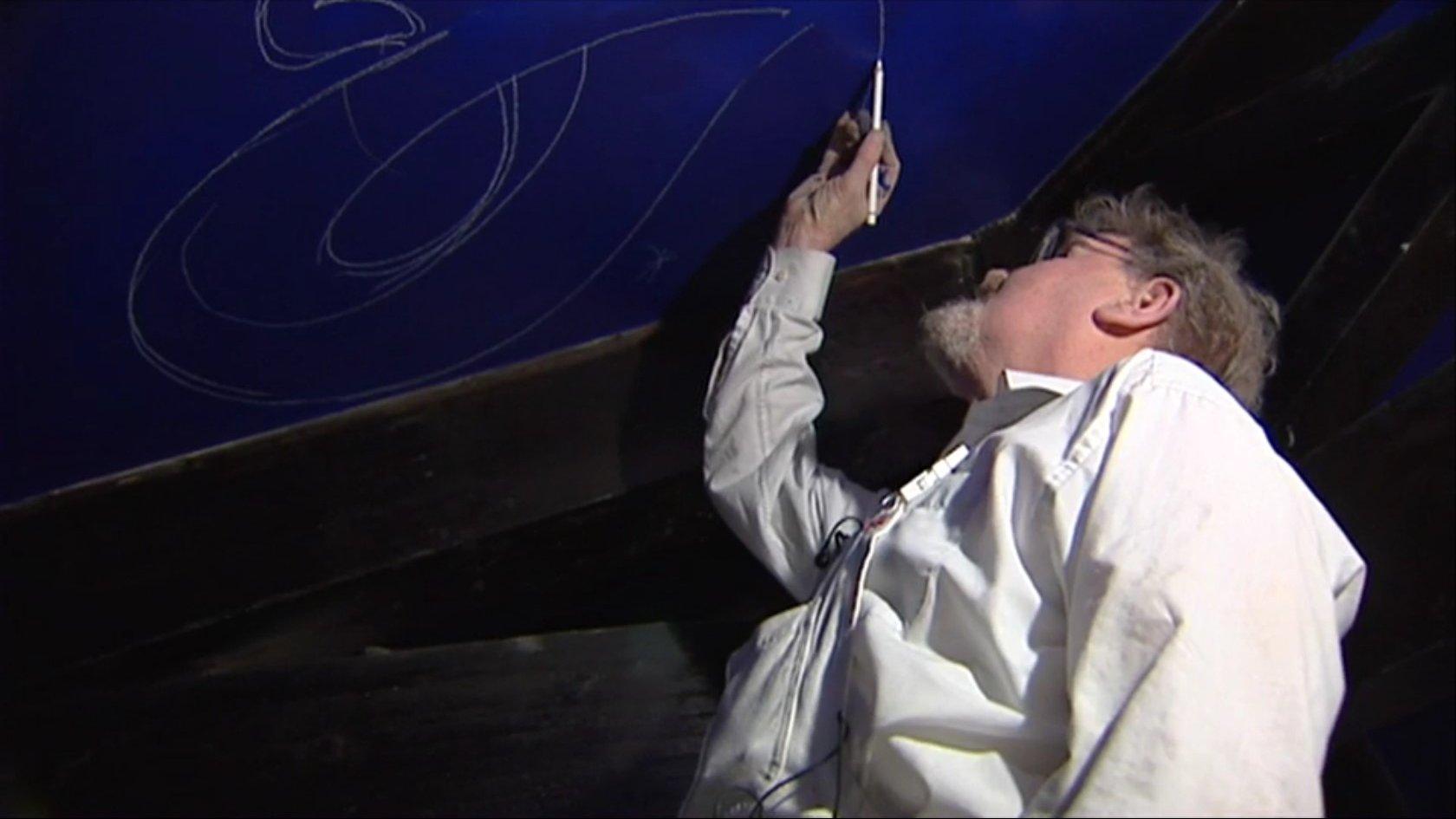

The Frankenstein patchwork of his face has echoes of Alasdair Gray's chiselled artwork and he uses the same gentle accent and singsong voice as Gray himself.

"I listened to tapes of Alasdair Gray," he said," and even though I wasn't trying to copy that accent I liked how he spoke and he had a wicked sense of humour and I think he put a lot of himself into the character of Baxter."

The film has been garnering awards since it first won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival in September.

Last week it won two Golden Globes and is now being tipped for Bafta and Oscar success.

Willem Dafoe admitted he listened to tapes of Alasdair Gray to perfect his Scottish accent in Poor Things

"It's very much like a fairy tale for me," says Andrew Gray, who's seen the film seven times, including a special screening at the Glasgow Film Theatre and another in his neighbourhood cinema in Connecticut where he's lived for the last 30 years.

"It's not often you get invited to red carpet events, I know the experience is temporary but it's been good fun."

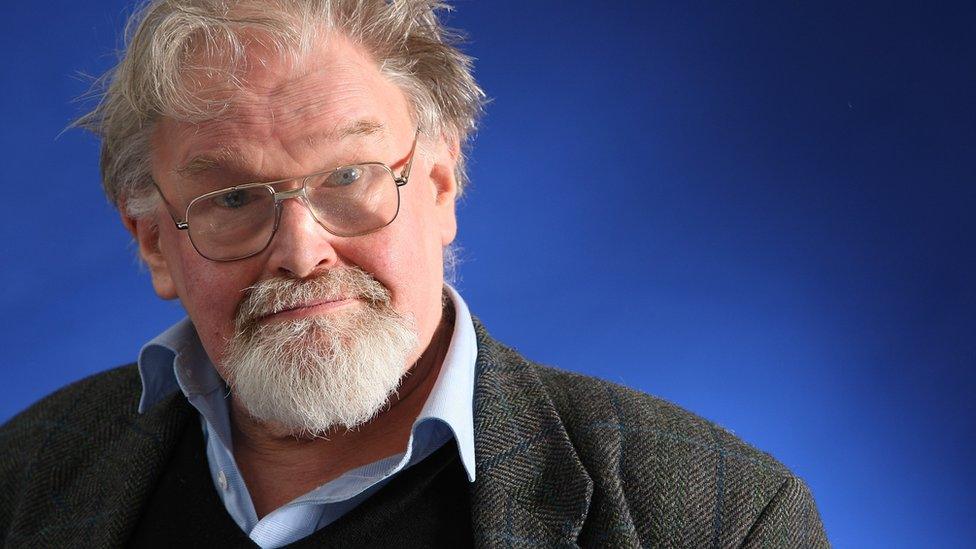

Gray, who died in 2019 at the age of 85 was one of Scotland's greatest artists and writers.

His first novel Lanark, published in 1981, is widely regarded as a landmark publication, responsible for a renaissance in Scottish writing.

One of his artworks, in private hands since it was created in the 1950s, sold at auction last week for a record £42,700.

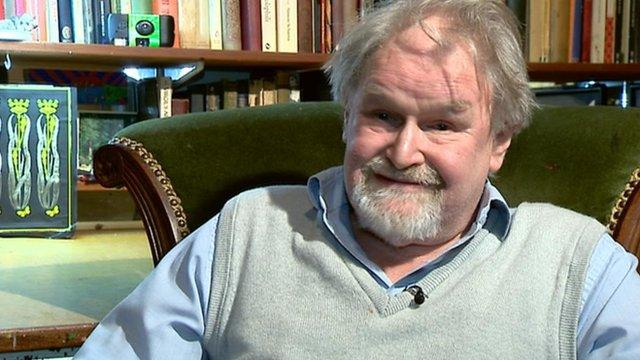

Alasdair Gray's son Andrew is glad the film will introduce more people to his father's work.

Andrew Gray believes it's long overdue attention.

"I think Alasdair has been neglected over the years and I'm hoping this will being more international attention to his work," he said.

"The limelight that this film has shared onto his work is certainly going to promote his writing and his art. It's going to bring new readers back to the book."

And that's the hope they have at the National Library of Scotland which holds his literary archive.

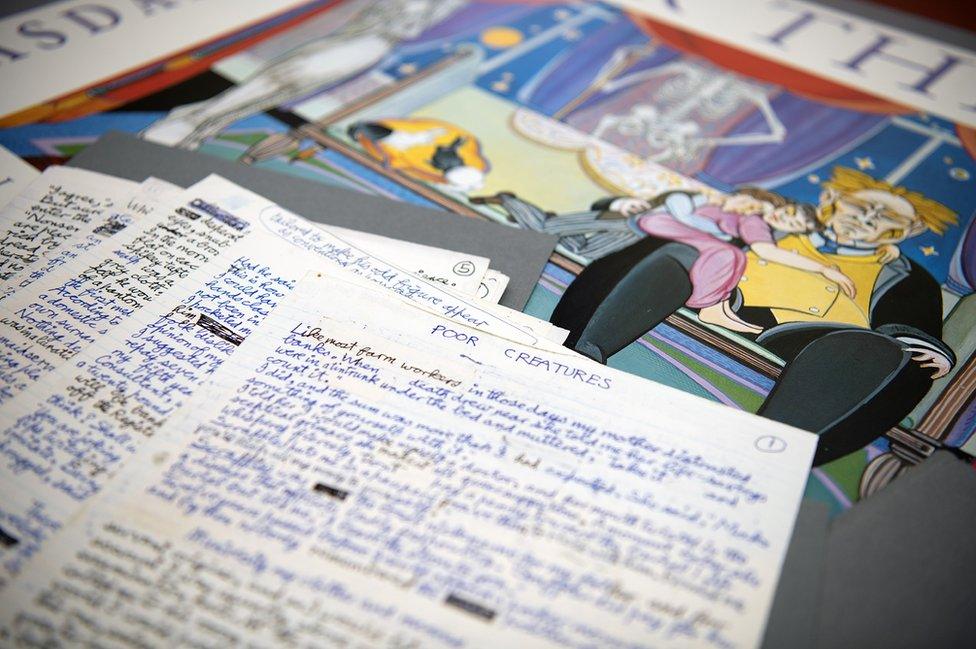

It includes handwritten notes, manuscripts, artworks and letters. There are three early versions of Poor Creatures, which would go on to become Poor Things.

In the correspondence is a letter from Gray to Yorgos Lanthimos after his visit to Glasgow, wishing him the best for his film adaptation.

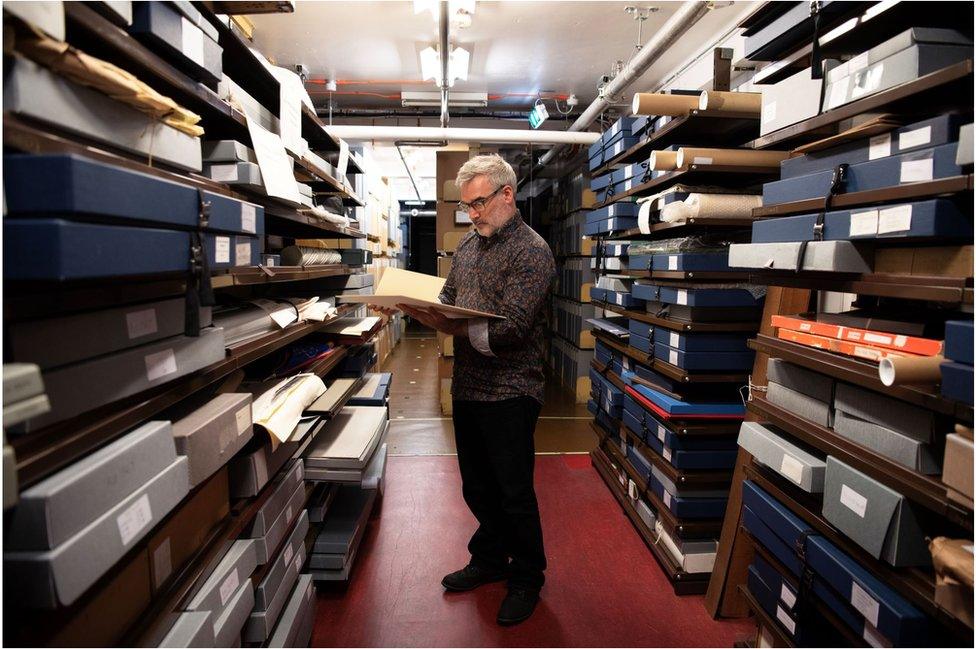

Colin McIlroy, curator of modern literary manuscripts said: "There are hundreds and hundreds of boxes.

"And it covers pretty much the working process for almost all of his written output: novels, short stories, dramas, radio adaptations, film scripts, diaries, and correspondence."

The archive gifted by Alasdair Gray to the National Library of Scotland

Some of the archive is available for consultation in the library's reading rooms but with 200 boxes, spanning a career of almost seven decades, the library is currently fundraising for a full time cataloguer.

Chris Cassells, head of archives and manuscript collections at the library said: "This is a collection of international significance - one of the biggest literary archives we have.

"We would very much hope that, given the amount of attention the film has received, given that it's really put Alasdair's name in the spotlight internationally, that people will watch the film before reading the book.

"And then they'll read other books and explore perhaps further into the hinterlands of Scottish literature."

Related topics

- Published29 December 2019

- Published28 March 2014

- Published29 November 2016