Face of Orkney's St Magnus reconstructed

- Published

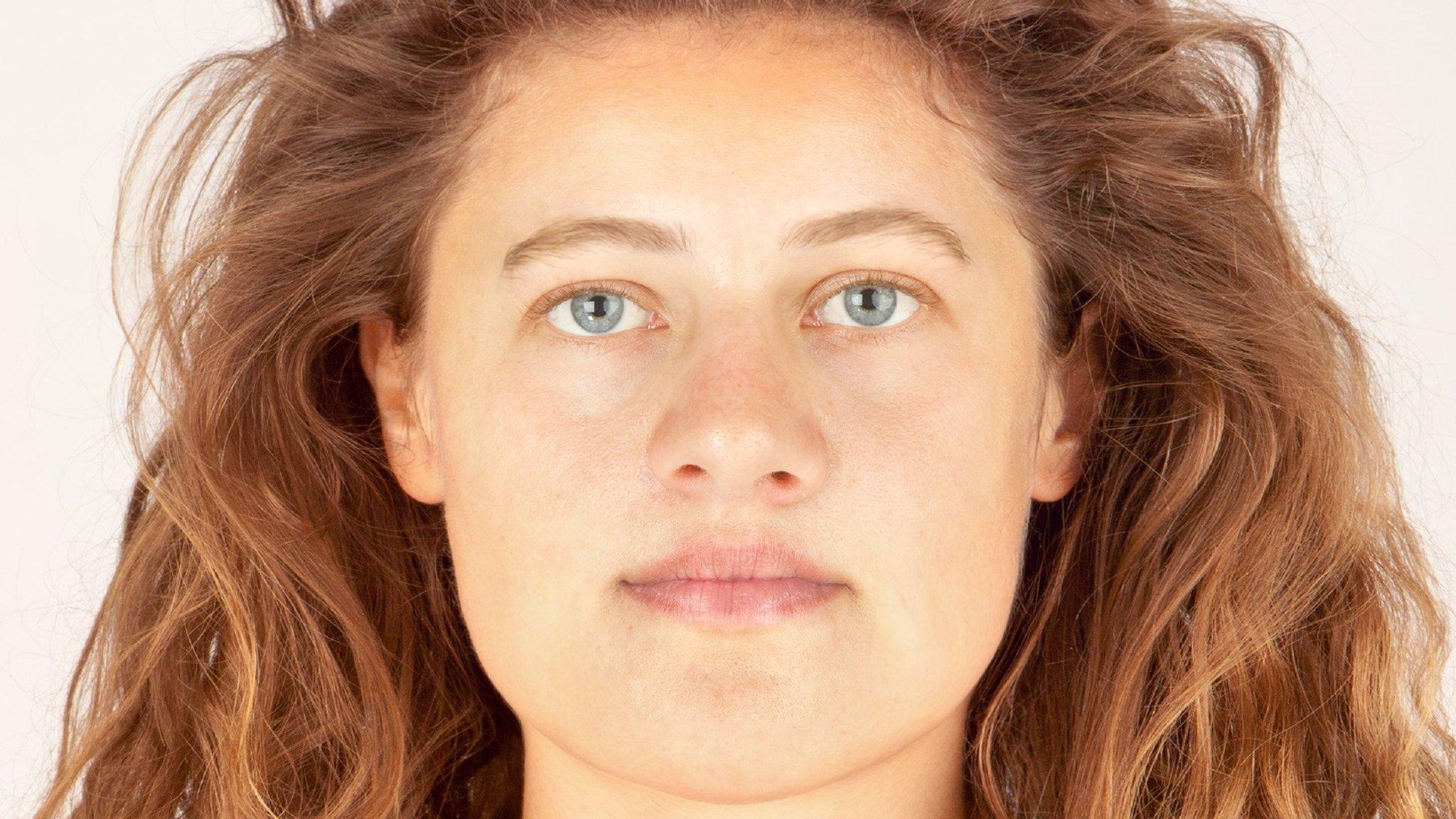

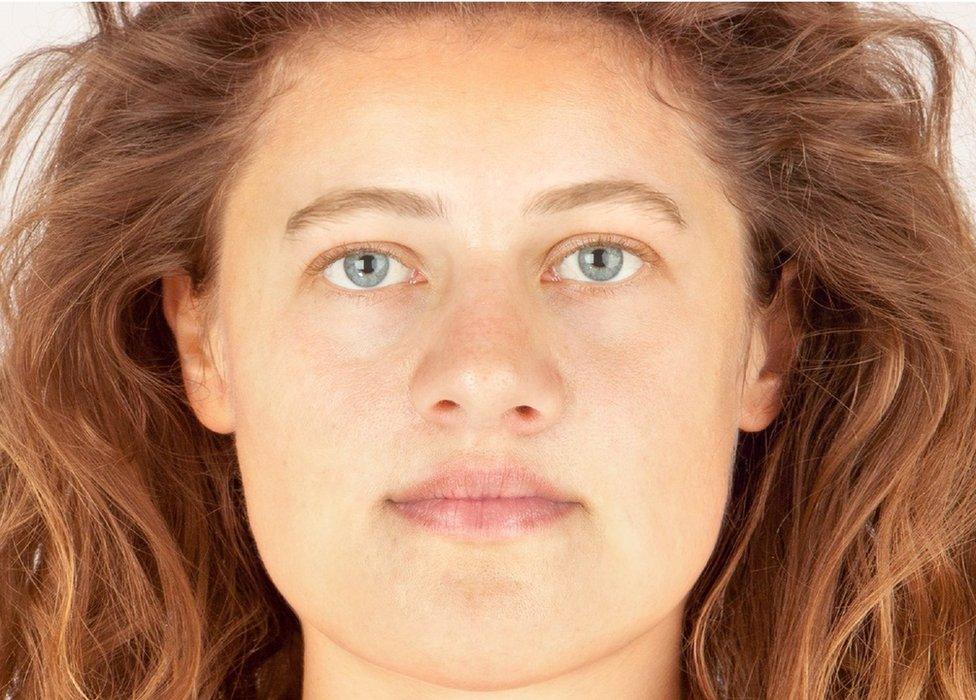

Forensic artist Hew Morrison used specialist computer software for his reconstruction of St Magnus

A facial reconstruction has been made of Orkney's St Magnus to help mark the 900th anniversary of his death.

Forensic artist Hew Morrison's research included studies of photographs taken in the 1920s of what is said to be the skull of the 12th Century Norse earl.

Before sainthood, Magnus Erlendsson shared the earldom of Orkney with his cousin, Hakon.

Hakon's jealousy of his cousin's popularity on the islands led to Magnus being put to death.

Although the date of his martyrdom is uncertain - they range from days in the years 1115 to 1118 - Orkney's annual St Magnus International Festival has chosen 2017 to mark the anniversary, external.

University of Dundee graduate Mr Morrison, whose other reconstructions include that of a Bronze Age woman buried in the Highlands, hopes his work on St Magnus will be displayed during the festival.

A photograph taken in 1925 of the skull found in a wooden box in Kirkwall's St Magnus Cathedral

St Magnus' life and death are a feature of the Orkneyinga Saga, external, an interpretation of Orkney's early history, including the conquest of the isles by Norway and the islands' earls.

The saga, written between the late 12th and early 13th centuries, tells of the collapse of the cousins' shared earldom. Hakon turned against Magnus and eventually betrayed him and had him executed.

The doomed earl's head was split in two by an axe, according to the saga. Miracles were said to have happened where Magnus was buried, including rocky ground changing into a grassy field.

Shape of skull

Centuries later, in 1919, a wooden box with a skull showing a wound and an assortment of bones inside was discovered during renovations to St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall on Orkney.

A University of Aberdeen professor and an Aberdeen church minister examined the bones and determined that they must be Magnus' remains. The relics were interred in a pillar of the cathedral.

Mr Morrison said he first heard the story of the bones when he was a boy.

He said: "I had forgotten about it until I visited Orkney back in 2015 whilst working on another facial reconstruction project.

"Understanding that the bones are permanently inside a pillar of the cathedral, thus inaccessible, I wondered whether there had ever been decent enough photographs taken of the remains that could be used to recreate a two-dimensional facial reconstruction.

"I managed to track down through Orkney Archives excellent photographs taken in 1925 that were suitable to use."

The relics of St Magnus are held in the care of Kirkwall's cathedral

A wooden box found in 1919 is believed to have held the relics of St Magnus

Mr Morrison has used computer software to create his reconstruction, drawing on what is shown in the vintage photographs to help guide the shape of skull.

He said: "The photographs from 1925 were fortunately of a good quality, but most importantly a scale ruler was photographed alongside these photographs, which allowed me to scale the skull up to life size.

"The missing jaw was re-created using a formula from the fields of anthropology and orthodontics.

"For this part of the reconstruction, I worked alongside my friend Keli Rae who is also a forensic artist and had previously used this method for replacing missing jaws prior to reconstructions."

Mr Morrison's other work has included a facial reconstruction of a Bronze Age woman who was buried in the Highlands

The reconstruction of the Bronze Age woman also involved research of a skull

Mr Morrison also drew on modern data of male European tissue measurements to gauge the skin depth for his reconstruction.

But he said: "An individual's hair and eye colour cannot be determined from the anatomy of a skull.

"No DNA/isotopics from samples of bone were available that would have helped to determine hair and eye colour.

"Although there were no visual records such as illustrations or paintings of St Magnus created during the time of his life, there are depictions of him in the form of stained glass windows and statues, but these were created many years after his death."

He added: "Taking into regard St Magnus's Scandinavian ancestry, light-coloured hair and blue eyes were added to the face."

Orkney's St Magnus festival will be held in June.

- Published29 July 2016