The life-saving machine developed in Aberdeen

- Published

The world's first full-body Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) prototype is on display in Aberdeen Royal Infirmary

The world's first full-body MRI scanner was cobbled together with copper pipe from a local plumber and a tube from a children's play park, according to a member of the pioneering team behind it.

Aberdeen University researchers were at the forefront of developing ground-breaking Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) technology that would go on to save lives across the world.

Prof Tom Redpath, who was a young PhD student at the time, says no-one had any idea how successful and important the MRI scanner would become.

Magnetic resonance imaging uses strong magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed images of the inside of the body.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The Mark I prototype, which is now displayed in a special gallery at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, was a gigantic step forward.

It was first used on 28 August 1980 on a Fraserburgh man who was battling terminal cancer.

It went on to scan more than 1,000 patients before it was replaced by an updated model three years later.

Looking at the original scanner, Prof Redpath, who retired seven years ago, says: "It's completely unlike a modern MRI scanner.

"There is no plastic facing to it, so you can actually see the guts of the thing and recognise the pieces of coils and copper and magnet that would actually make up a modern scanner."

The Mark I was cobbled together using copper from a local plumbers' merchant

Prof Redpath says the strength of the magnetic field generated by the 1980 scanner was "peanuts" compared to modern machines, which are up to 100 times stronger.

"Despite that, it still produced usable images," he says.

According to the professor, a lot of people at the time did not think the technology was worth pursuing because they said it would never work and they already had CT scans.

He tells BBC Scotland: "Our department was quite adventurous in what it got up to.

"I was quite young at the time and it just seemed like a very interesting thing to be doing.

"Very quickly after scanning that first patient we realised this was a) going to work and b) going to be useful."

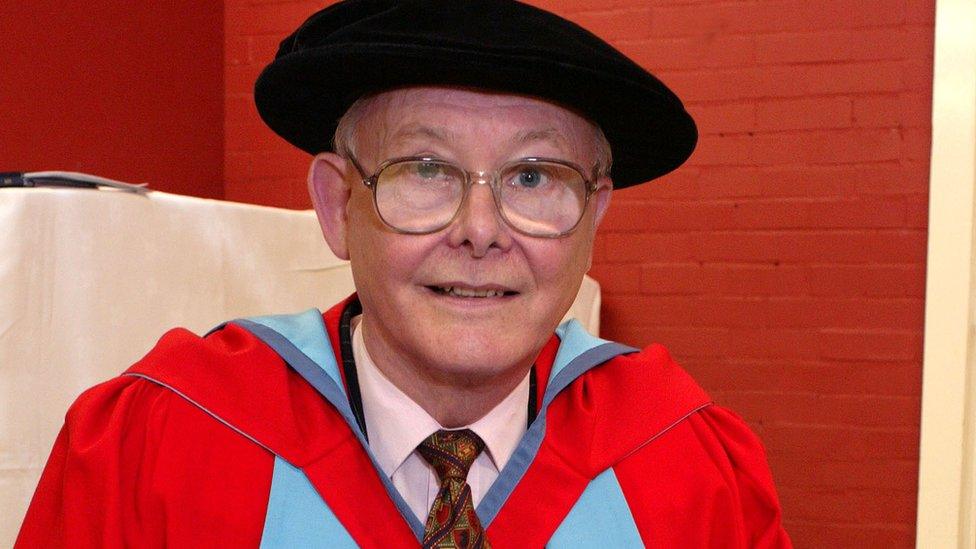

Prof John Mallard, who led the Aberdeen University team which developed the scanner, said: "The driving force for us was the fact that we had X-rays that were telling us everything about the bones.

"But we had absolutely nothing that was telling us about the soft wet tissues within the body.

"And that's what MRI did."

MRI scanners are now used routinely around the world

Prof Mallard, now 91, said: "What I remember most about that time was that it was excellent for picking up multiple sclerosis (MS).

"I had a cousin who died of MS so I was particularly pleased that we'd found something that if he'd still been alive it could have helped him."

The technology behind MRI was developed in the 1970s by the late Sir Peter Mansfield and his team at the University of Nottingham.

Sir Peter shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2003 with the inventor of the technique, US chemist Prof Paul Lauterbur.

But it was the team in Aberdeen that was responsible for developing the world's first full-body MRI scanner.

It obtained the first clinically useful image of a patient's internal tissues using MRI.

Prof Mallard and his team are also credited with technological advances that led to the widespread introduction of MRI across the world.

Prof Redpath says he is "proud" of being part of the team that developed MRI but was disappointed that the UK quickly lost its lead in the field to other countries such as the US and Germany.

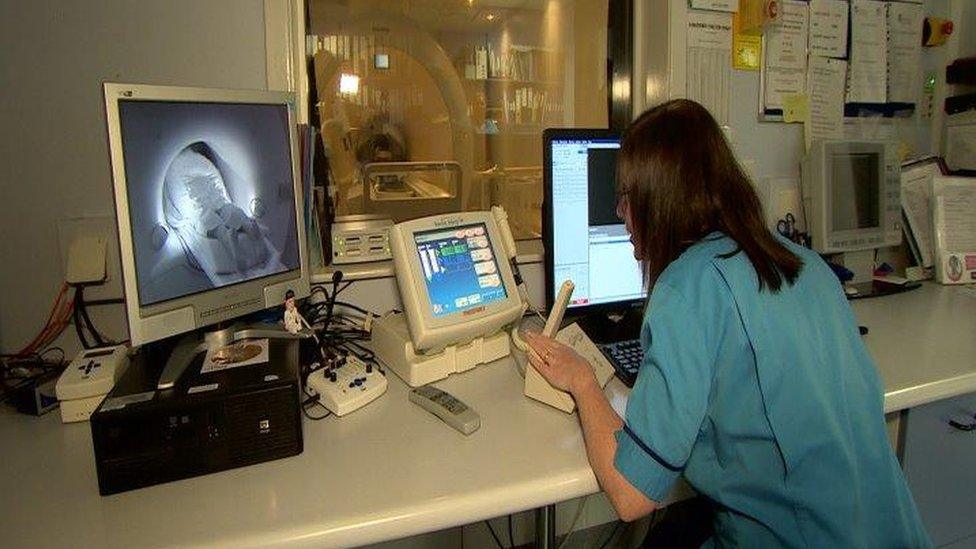

A patient is monitored undergoing an MRI scan at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary

He says MRI imaging has developed far beyond what was thought possible at the time, especially in areas such as functional scanning of the brain.

"The difference between the Mark I and a modern scanner is a bit like the difference between a World War One fighter aircraft and a modern Typhoon jet fighter," he says.

"The basics are the same but the actual technology has moved on so much. It's just incredible."

Alison Murray, professor of radiology at the University of Aberdeen, says the significance of the development could not be underestimated.

"I think it was revolutionary," she says.

"MRI is probably the biggest game changer in modern medicine because we can do so much imaging.

"I can honestly say they save lives. They show us the extent of pathology, they help us diagnose pathology.

"We can pick up lesions when they wouldn't otherwise be visible. That saves lives by early diagnosis."

Prof David Lurie said the new scanner has been likened to "100 MRIs in one"

Breast cancer survivor Estee Coetzee says having an MRI can be "a little bit of a daunting experience".

"But they make you as comfortable as you can be," she says.

"They make a lot of noise which is fine because they give you headphones and they even let you choose the music you want to listen to."

Ms Coetzee was only 28 when she was diagnosed.

Three years on she is cancer-free.

The information from the MRI scans shaped her treatment.

She says: "It was just really to have not missed anything that was not seen under CT or ultrasound - to make absolutely sure we'd not missed a hidden lesion because MRI is so much more powerful."

Patients are already being scanned in the Fast Field Cycling Machine, the next generation of MRI.

It is described as "100 MRIs in one" and is still sitting in the workshop where it was built.

No doubt it will one day follow its predecessor and become just another part of everyday medicine.

- Published26 June 2018

- Published21 November 2017

- Published9 February 2017

- Published23 January 2017