A bomb, a song, a rabbit - the first WW2 bombs to fall on British soil

- Published

A rabbit was the victim of the first bomb to hit British soil in WW2

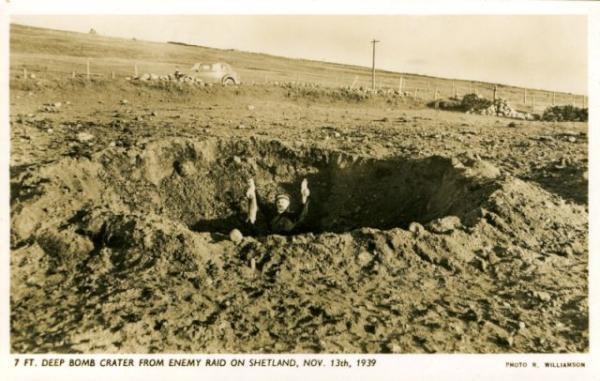

On 13 November 1939, the first German bombs to fall on British soil exploded at Sullom in Shetland.

The attack brought home the reality of war to one of the remotest part of the country.

The bombing, just weeks into the war, was recorded in a curious set of photographs - but therein lies a mystery.

The bombers were targeting vessels docked in Sullom Voe - two cruisers, HMS Cardiff and HMS Coventry, a number of cargo ships, and nine flying boats.

Local historian and blogger Richard Ashbee said the raid appears to have been based on some preliminary reconnaissance the previous week.

"They (Germany) might have thought Shetland was going to be a base long-term," says Mr Ashbee.

But the impact on Shetland was "nil ... less than negligible" according to curator of Shetland Museum and Archives Dr Ian Tait.

That was because not one bomb hit its target.

'Curiously intact'

A number fell into the sea and peat land, with one "almost hitting a school", according to Mr Ashbee.

But the four that fell on rocky ground seemed to claim a victim - a rabbit.

The photo "immortalised" Britain's first bombing raid.

There appears to be photographic evidence of this - a man holding the unfortunate animal inside the crater - but not everyone is convinced.

"The rabbit in the photo is curiously intact," observes Dr Tait.

"The fact is a rabbit was killed in the attack, but was eaten. Some people claim this rabbit (in the photo) is a prop - that's an over-rectification of history."

So how did this photo come to be taken and is there any truth in the story that a rabbit was killed?

Dr Tait explains: "The rabbit in the photo isn't the one the bomb killed."

Robbie Williamson, a photographer from Lerwick, had a keen eye for a shot. When he heard about the rabbit's death, he went to record the "historic bombing" for the purposes of a postcard.

But his camera wasn't the only gear he brought.

"He had a good eye for something that would sell. But before going north he went to a butcher's shop to buy a rabbit," explains Dr Tait.

Recreating the incident, Williamson asked his driver to stand in the crater, holding up the rabbit, "immortalising the event".

"Over the years, it became accepted this was the rabbit the bomb killed."

Run Rabbit Run

This wasn't the only time Robbie Williamson was to demonstrate his talent for reimagining Shetland's war history.

Some weeks later he photographed the aftermath of a further bombing in Shetland - and drew in the aircraft that supposedly dropped the bombs.

Comedy act Flanagan and Allen performing at the BBC

The rabbit incident also triggered another intriguing myth surrounding the bombing of Sullom.

At the time "Run Rabbit Run" was a popular song, recorded and performed by comedy double-act Bud Flanagan and Chesney Allen.

"Part of the mythology, fuelled by Williamson's photo, is that this is the rabbit the song was written about," explains Dr Tait.

But this can't be the case - the song was part of a London stage act performed at the start of October 1939, a month before the bombing.

"What the Sullom rabbit's death ensured was the instantaneous popularity of the song," said Dr Tait.

"There were spin-off versions made with alternative lyrics but it wasn't written about that rabbit - the rabbit popularised the song."

Vulnerable island

Recreated photos and popular songs aside, what long-term effects did the bombing have on Shetland?

For Shetlanders, he thinks the attack must have been a shock.

"They would have felt far from the main centre of population and industry," he says.

But the attack may have also alerted authorities to the risks of basing vessels in Shetland.

"It's my interpretation, but I daresay that for the War Office, it exposed the fact that Shetland was vulnerable."

It's a notion historian Richard Ashbee agrees with.

"Shetland has a massive coastline - it could have easily been invaded and nobody would have known until it was too late."

As the war progressed, more and more troops and vessels were stationed across Shetland, particularly when Nazi Germany invaded Shetland's eastern neighbour, Norway.

The population of the islands "more than doubled" as troops were stationed from Sumburgh to Unst.

"Shetland was invaded, but by friendly troops," he adds.

- Published14 October 2019

- Published8 September 2019

- Published10 November 2018