Banking on eradicating poverty

- Published

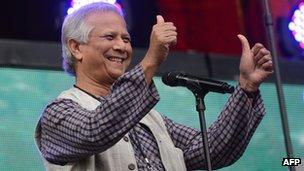

Prof Yunus founded the original Grameen bank in Bangladesh in the 1970s

Nobel Prize winner Prof Muhammad Yunus spends much of his life travelling the world, furthering his work aimed at moving towards eradicating poverty.

This week his focus will be in Scotland, where he is due to be welcomed as Glasgow Caledonian University's new chancellor.

Prof Yunus is one of the most influential pioneers of micro finance.

His new university role comes as plans advance for the opening of the first Scottish branch of the Grameen Bank, which he founded many years ago.

In her corner office, Glasgow Caledonian University Principal Prof Pamela Gillies is explaining how she sees the possibilities offered by the bank.

"I think this is going to be one of the biggest public health interventions in Scotland since the banning of smoking in public places," she says.

"It is an idea that crosses cultures and economic boundaries and gives control and responsibility for the health and well-being of their everyday lives back to the poorest people in society."

The original Grameen bank was founded in Bangladesh in the 1970s.

Prof Yunus lent a small amount of money to a group of villagers at a rate which would allow them to make a profit from their small businesses and still pay him back.

Small beginnings

From small beginnings an international microcredit revolution was born, lending to millions around the world.

"I bought the feed, I bought the chicks," explains one woman in Zambia, who took out a small loan which allowed her to begin keeping chickens.

"It has really helped me so much. We didn't know about business and we were taught simple book keeping."

But can an idea like this work here?

Glasgow Caledonian has facilitated the setting up of the Grameen Scotland Foundation. It, in turn, will support the launch of the bank. It is thought there could be borrowers by the New Year.

The university has also set up the Yunus Centre for Social Business and Health, which - among other things - will analyse how the bank works.

Prof Gillies says she hopes the bank can change lives and inspire a new generation of people who feel constrained by their current welfare circumstances.

She explains: "We hope to encourage them to take themselves out of poverty, take control over their own lives and this will be, in the long-run, tremendous for people whose families have spent three or four generations in a workless situation. It should really transform their lives."

Transformation

There's a transformation of another kind taking place in the Provanmill area of Glasgow.

At three or four tables people have come to a lunch club run by local women. There is lentil soup, as well as a roll and sausage on offer, a chance to chat and a couple of games of bingo - all for a couple of pounds.

The women - all volunteers - who run this place are part of a self-reliance group facilitated by the Church of Scotland.

Each member contributes a small amount of money each week which goes to buy ingredients for the following week.

The original Grameen bank was founded in Bangladesh in the 1970s

One of those involved is Jake Crawley, whose dream is to set up her own laundry and create herself a job.

The ultimate aim of this project is to help her do that - there are potential premises in the church where the lunch club is run.

Since they set up about 18 months ago, the women have driven the lunch club forward by their own efforts.

Now they are getting together costings with a view to setting up the laundry as a business.

For that they will need some kind of micro loan and Ms Crawley says she will need help to ease her off benefits and hopefully into her own business.

"Myself, I would rather move on," she comments. "Get our laundry set up and I create myself a job, because that's what I want to do - not because a job centre or work programme is forcing me to do jobs."

The term micro credit covers many different models of doing things.

Some micro credit, for instance, is highly commercial, some has been unregulated.

'Good record'

Prof Cam Donaldson is the Yunus chair in social business and health at Glasgow Caledonian University.

Part of what his centre will be doing is looking at how this model works when introduced to a more advanced economy.

He said the west of Scotland had a good record of alternative financial intermediaries, such as credit unions.

"But I think it's still fair to say that those institutions don't target, as specifically as Grameen does, those that are worst off in society and thinks about such people as having their own ideas, their own potential and to try and encourage that."

Yet micro finance hasn't always worked well. In south east India, for instance, there has been a crackdown by the state government on micro-lenders after reports of over-lending.

Micro 'trap'

Some believe that micro finance is not the way forward.

Milford Bateman - a consultant in local economic development - argues there is evidence a lot of micro finance is used for consumption spending and can trap people in simply servicing loans. And he believes there are other problems.

"There's absolutely no evidence that more and more micro-enterprises will somehow lead through some unspecified mechanism to economic development and poverty reduction," he adds.

Prof Donaldson agrees there have been problems in some areas, where micro credit has been unregulated. More established institutions like Grameen and others, he says, don't operate like that.

"Where we need to get to, to grow the economy, is the bit in between individual poor entrepreneurs and larger businesses, which are small and medium-term enterprises, and that's what needs to be supported," he argues.

You can hear more about micro finance by listening to BBC Radio Scotland's Business Scotland on BBC iPlayer and by free download.

- Published6 August 2012

- Published1 July 2012

- Published2 March 2011

- Published27 January 2011