Heat is on: Why are energy bills so high?

- Published

Household bills have more than doubled over the past ten years

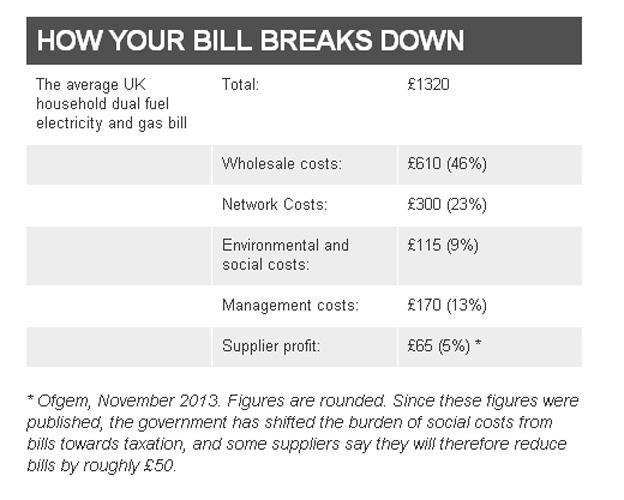

Household energy bills are hurting. In the past ten years, they've more than doubled. In 2004, the dual gas and electricity average annual bill was £590.

It rose most steeply in the following five years to £1,205, and by last year, it was at £1,320.

For families in bigger homes, and those in poorly insulated housing, the pain of that rise is particularly acute.

And it has fuelled the problems from inflation being well above target for much of the past five years - only returning to its 2% target in this month's figures.

While that has been the case, average pay has lagged, and household budgets have been squeezed.

The problem has put pressure on government and on the big energy suppliers to ease the pain.

Last month, the government took away a levy through which customers paid to help lower-income households with their bills. In turn, that means taking about £50 off the average bills of companies, including Scottish Power and SSE (Scottish Hydro), over the next few weeks.

Hidden costs

Another tranche of the household bill is being diverted into paying for the expansion of renewable energy, such as wind power. And that has built up political pressure to cut back on Britain's commitment to expansion of renewables.

But there's another cost in the bill. It's hidden, it's kept confidential, and yet it's for a part of the industry that appears to be on the consumers' side.

This is the cut of the bill taken by price comparison websites, in return for referring customers. The recommendation to switch creates churn in the market, and it is seen by supplier companies as worth paying high fees to the websites.

Whether or not customers choose to use the sites, the cost to the supplier is embedded within bills for all customers.

Industry regulator Ofgem has a voluntary code of conduct for price comparison websites, which requires them to say on their sites they have a commercial relationship with companies mentioned in quotes. But there is no requirement for details of what that relationship involves.

David Hunter, an energy industry analyst with Schneider Electric, explained how it works for BBC Scotland's Reporting Scotland.

"If you use a price comparison website, that website or broker will be paid commission by the successful supplier for placing business through them," he said.

"They're very secretive about the amount of money they make from doing that.

"We know the supplier makes a profit for billing you of about £60 a year, and bearing in mind what we know about supply cost information, I wouldn't be at all surprised if the websites and brokers are making £60 or perhaps more out of every customer's annual bill."

BBC Scotland asked the big six supplier companies and some leading price comparison websites what is paid for this brokerage service.

Those who replied said the information was confidential. Npower went further, explaining the service was useful to customers, and that it reckons the cost to consumer is lower than David Hunter's estimate, at £20 to £40 per customer per year.

Lawrence Slade, chief operating officer, with industry body Energy UK, spoke on behalf of the industry, but said he did not have contractual details from member firms. He said the use of websites replaced a more conventional form of selling that has landed the industry with large fines for misleading customers.

"If you go back 10 or 15 years ago, the internet was in its infancy, and we didn't have this as a channel of sale," he said.

"We were reliant on doorstep sales. Of course, the industry has now stopped doorstep sales as a channel of selling, and we're open to these new channels, such as comparison websites and collective switching.

"So we view these things as different channels of sales to let people engage in the market. Costs associated with these sites would be part of the overall marketing costs of any energy companies business, large or small."

'Improve transparency'

The other controversial aspect of household energy costs is the integration of supplier companies. The large ones have generating capacity, and the retail divisions buy from those power stations and gas producers.

The level of profit in generating electricity in 2012, according to Ofgem, was 20%, down from 24% the previous year, whereas the profit from retail averaged 5% last year.

The industry says such profits are necessary for investment in replacement power stations and grid connections. They say profit is a less meaningful measure of their operations than Return on Capital.

They also integrate with gas and electricity supply at its source to protect the retail supplier division against fluctuations in prices and uncertainty of supply from the market.

Some companies have responded to pressure to put some of their wholesale energy into the market place. But David Hunter says there is a case for much more of it to go into the market, so that entrants to the energy markets could have a wider range of options on buying energy in short or longer-term deals.

"One thing stopping smaller energy companies coming in and shaking up competition is that that power isn't going to the market," he said.

"We would separate the power stations from the billing arms of these companies, and make the power go into the market, so the smaller companies can get involved on a level playing field and offer competitive deals to us at home."

Lawrence Slade of Energy UK emphasises that some energy is being put into the marketplace for that purpose, and that the divisions are being ring-fenced to help improve transparency.

The energy companies face continuing pressure to pare down costs to consumers, particularly from Westminster politicians preparing for the May 2015 election.

At least privately, they admit to having been put in a weak position by their customer sales methods landing them with large fines.

But in recent months, they have been resisting some of that pressure - highlighting the government-imposed elements of energy bills. They have also been trying to explain to customers and politicians that none of the solutions to higher bills is simple.