Heated politics of Longannet going cold

- Published

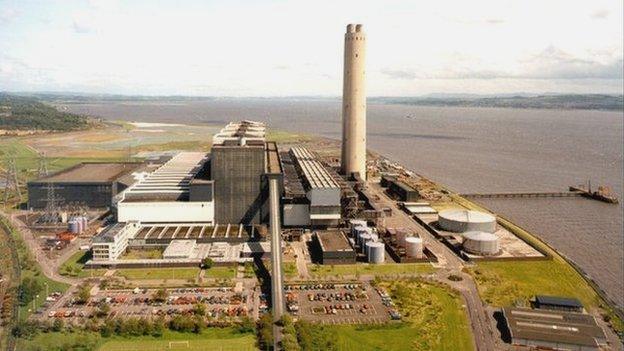

The closure of Longannet is almost certain to be brought forward to next March

Longannet power station is a bit of a monster. At 2,400 megawatts capacity, the huge plant on the banks of the Forth can keep the lights on for most of Scotland.

Recently, it's been sweating its 42-year-old sinews to do so, particularly when the wind drops and all those turbines stop supplying the power grid.

The Fife monster's days were numbered, however. While burning all that coal, it was facing a steeply-rising bill for emissions. And once it has burned through its licence conditions, it was due to close in 2020. That was the intention of government policy, and it has had cross-party support.

However, that date is almost certain to be brought forward to March 2016, following Longannet's failure to win the National Grid auction for back-up supply to ensure voltage remains steady.

With closure, 270 jobs will go, plus those in the supply chain, including freight operations form Hunterston. Scotland's struggling coal industry will struggle even more.

The green lobby won't be shedding a tear. But the sense of political crisis around Longannet exposes a large gap in planning for the country's greener energy future.

High voltage

To explain, let's back up. Scotland has been producing more thermal power than it needs, from coal, nuclear, hydro and increasingly - when the weather's right - from wind.

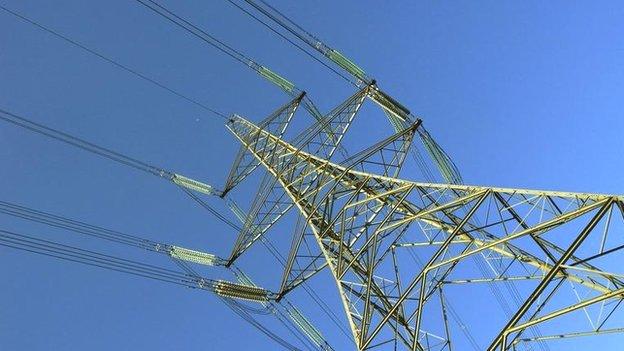

So it has long been an exporter of power. And given a strong breeze, exports are getting bigger. That's why more capacity is required to transfer that power to population centres in England and beyond, into the increasingly integrated European market.

High-voltage links from the Highlands are being upgraded (remember the Beauly-Denny line controversy?), as is cross-border transmission. A very expensive sub-sea cable is being sunk between Ayrshire and Merseyside, and a marine cable off the east coast may follow.

This works in both directions, so when Scotland's renewable generation isn't generating, the grid in Scotland can draw on gas, coal, nuclear, solar and other renewable power generation from England and beyond.

Until that transmission capacity is in place, which will take another two years, the National Grid is concerned that it needs back-up capacity to ensure a reliable voltage.

And that's why it asked thermal generators to make their bids as the most competitive option for that back-up.

Nuclear power was not included, as it lacks the flexibility to respond to unexpected drops in supply elsewhere.

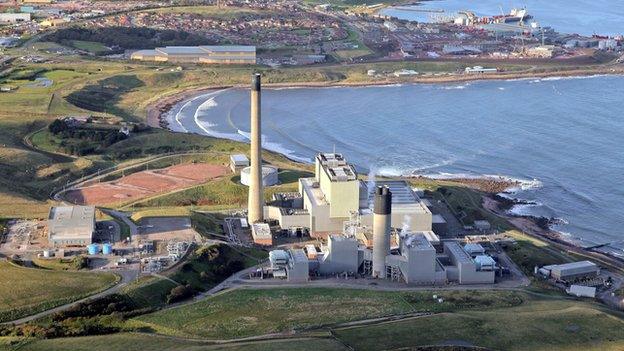

So the bidders were coal-burning Longannet, gas-burning Peterhead, owned by SSE, and an innovative solution from a company called Tower Bridge Ventures, which wanted to moor gas-burning power turbines on barges.

Pumping power

Having lost, Longannet is fast running out of steam. Its owner, Scottish Power, had hoped to keep going to 2020 with reduced transmission charges to offset the rising costs of its emissions.

Ofgem, the energy regulator, was reviewing the cost to generators of pumping their power into the grid.

For many years, that has been heavily biased towards encouraging electricity generation near where it's consumed, in cities, and mainly in English cities.

So if you generate power in London and along the English south coast, you get a subsidy from the grid. If you generate it in northern Scotland, you pay a hefty whack for the privilege (and if you're a customer in northern Scotland, there are lower bills as partial compensation).

With policy pointing to much more renewable energy, which is most efficiently generated where the wind blows most strongly (that being northern Scotland), Ofgem's Project TransmiT reviewed those charges and revised them - a bit.

But the revision doesn't come close to making Longannet's numbers add up. Its transmission costs next year fall from £40m to £34m, and then go up again the following year.

Ageing fleet

All this makes Longannet a hot political potato, and it's being super-heated this close to a Westminster election.

Its owner, Scottish Power and parent company Iberdrola, are being criticised by Labour for not investing in emissions abatement technology.

Ofgem and the UK government are being criticised by the Scottish government for charges that discriminate against Scottish generators.

The Scottish government is being criticised for an energy policy that is too dependent on renewable energy.

And south of the border, things aren't looking too good either. The ageing fleet of thermal and nuclear power stations are being closed down at quite a rate, and nothing like enough preparation has been done to replace them.

The political row is over Longannet's failure to win the auction. But that eclipses the celebration for the other side of this story: Peterhead won!

Industry insiders reckon Peterhead is about 60% cleaner per unit of energy than Longannet

The Aberdeenshire plant also faces very high transmission charges. But they can be offset by much lower emission costs from burning gas. Industry insiders reckon Peterhead is around 60% cleaner per unit of energy than dirty old king coal at Longannet.

The £15m capacity payment, added to payments for actually generating the back-up as necessary, gives it a financial lift at a time when gas-burning is uneconomic for all generators.

SSE has pulled back on Peterhead's operational capacity for that reason. And last year, when it was in a different auction to provide back-up capacity, it failed Ofgem's technical test.

But it is the last remaining hope for Scotland to get on with the much-vaunted carbon capture and storage (CCS). That happens to have been the great hope for Longannet as well, until Scottish Power gave up on the expense and delays.

Signals at red

This is an industry which is very heavily regulated. It responds to market and regulatory signals.

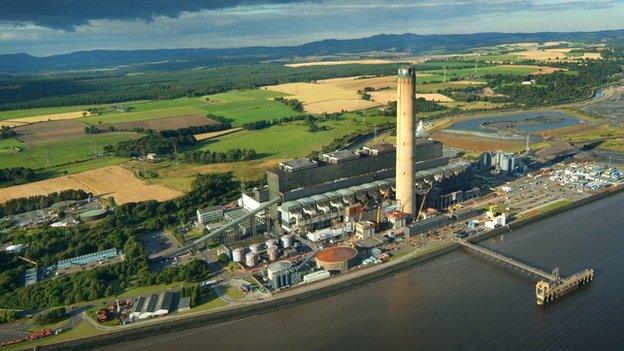

The signals, for now, are at red for old and new thermal capacity. Cockenzie in East Lothian could have gas turbines fitted where the coal-burners were recently shut down, but it makes no financial sense for now. Fracked gas could cut costs and make gas-burning economic, as it has in the US, but fracking is under a moratorium in Scotland.

The signals are at red for new nuclear power as well. Onshore wind is meeting opposition, offshore wind is failing to get its costs into a commercially viable condition, and wave power is becalmed by a lack of investment capital. At least tidal power is coming up the beach, though very slowly.

We could look to government to sort this out. But the election has thrown up a promise from Labour that it would put much tighter controls on household energy pricing. Not only has that pledge kept prices from falling, it also puts a chill on future investment in generating plant.

There are probably better ways of keeping the lights on.

- Published23 March 2015

- Published23 March 2015