The big clean up

- Published

Each digger at Glenmuckloch is capable of scooping up 15 tonnes

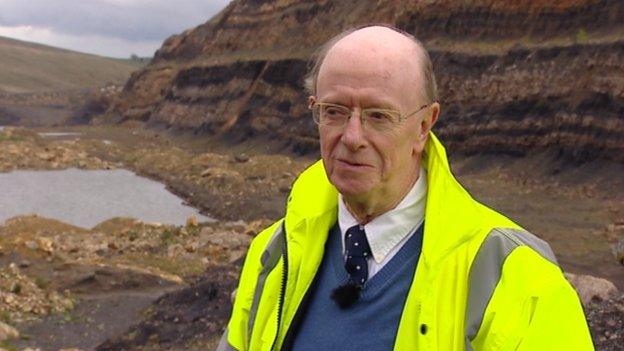

Russel Griggs has become one of Scotland's biggest landowners, to his astonishment.

The businessman and professor has control over around 10,000 acres of land, much of it in the Southern Uplands where South Lanarkshire, Dumfriesshire and East Ayrshire meet.

These comprise seven sites of special industrial ugliness, because that is where vast diggers and trucks tore away at hillsides to expose coal seams.

When you visit them, the most striking thing is how fast this happened. They look like it should have taken centuries to have such an impact, yet most were worked in the past quarter century and for less than ten years each.

The area has been worked for coal for eight centuries, some of it deep-mined. Removing topsoil and rock to get at these narrow seams of soil only became commercially viable when the machinery got to the right scale and robustness.

I went with a TV camera crew to the Glenmuckloch opencast site near Sanquhar, being worked by coal company Hargreaves and on land owned by the Duke of Buccleuch.

We watched in awe as each scoop from the digger picked up 15 tonnes. Four scoops goes into each truckload. They could take 100 tonnes each, but that would not be an efficient use of the vast engines. For every tonne of coal removed, around 22 tonnes of rock has to be extracted around the coal seam.

For those who, child-like, wonder at the scale of these machines, the tyres give you some idea of the money involved. Each truck has six tyres, they cost £7,000 each, and because of wear and tear on rocks and gravel, they need to be replaced at least twice a year.

Undercut by fracking

For several other such sites, the money ran out. Fracking in North America undercut coal. US power stations were converted to cheap gas, so as demand for coal fell, the price plummeted.

Scotland had been the biggest player in UK opencast mining. At the start of 2013, the two companies dominating Scottish opencast production - ATH and Scottish Resources Group - went bust. About 1,000 jobs went.

The insolvency experts who took them over quickly found the firms were nowhere close to being adequately funded for the clean-up costs, to which they had committed.

Filling in the giant holes and landscaping Scotland's opencast coalmines would take almost as much earth-moving as the original mining. The cost of that is estimated at £200m.

But the liquidators had only £4m they could hand over, while councils had to go after the bonds (a form of insurance policy) which the companies had taken out.

Prof Griggs has enlisted school pupils to decide how the £100,000 a year income from Glenmuckloch's windfarms should be spent

According to Prof Griggs, if all the bonds were paid out they would raise perhaps £30m to £40m. But as some are being contested by insurance companies, he anticipates between £20m and £25m will be available to him.

The failure to fund the clean-up clearly reflects badly on the defunct firms, which had thought they could finance each restoration project with cash from the next site.

It also reflects poorly on the local councils, which failed to nail down the financial assurances when they awarded the planning approval. Fife was also caught by this. We're assured lessons have been learned, and it won't happen again.

But to salvage what it could, the Scottish government turned to Prof Griggs as its adviser on business regulation. It asked first if red tape was one reason things had gone so badly. His answer was that it was only a part of the explanation.

But having got him interested, ministers then asked if Prof Griggs would lead the newly-created Scottish Mines Restoration Trust, and do what he could to sort out the mess.

The Sanquhar resident began with that £4m budget, employing four people, to secure the sites, fence off ponds where swimmers sometimes unwisely go, and to monitor water quality.

He turned to a wildlife charity, and gifted it some moorland and forest. He is, cautiously, considering options on selling parcels of land to local farmers.

Pupil investment

Griggs has been working with the Duke of Buccleuch, owner of Glenmuckloch, from which £100,000 of community funds are expected to come from two wind turbines being installed this summer.

He said: "I'm getting on in life and I decided that if we were looking 25 years into the future, with £100,000 a year to invest in the community, maybe we should ask the young people to do it.

"So the investment committee - the people who'll make the decisions where the money will go - will be the rolling fifth and sixth form of Sanquhar Academy."

In their first year of operation, the pupil committee has compiled a short list of applications for funding, focussing on facilities for the young and for older local residents.

"Having worked with these young people for the last year in putting this together, they've risen to the task amazingly," said Prof Griggs.

"My Trust is giving them a little pump priming at the beginning.

"We've given them £25,000 to start, because it's unlikely that the income from the wind turbines will start to come through until August or September this year."

Spireslack is said to be a "geologists' playground"

Prof Griggs turned to the British Geological Survey to see if its members could make use of other sites. What they found astounded them. One told him - perhaps with a little exaggeration - that the Spireslack site in South Lanarkshire, excavated in only the four years to 2007, is the geologists' equivalent of the Large Hadron Collider.

The diggers have exposed layer upon layer of geological pre-history, ripe for study instead in place of geology textbooks or computer generated 3D images.

"This is a geologists' playground," Prof Griggs told me

"When they come here, they go gooey-eyed. These are things you won't see anywhere else in the world."

Where seams of coal and sandstone have been forced up by volcanic activity, and then cleared away in the 21st century, the sheer 'pavement' under it is exposed at around 45 degrees, offering an enticing prospect for geologists and for climbers and abseilers. The last thing they would want to do with £200m, if it were available, would be to fill it this 1km long, 80-metre deep valley.

The disturbed rocks offer abundant opportunities for fossil-hunters. Nearby, flattened terraces of disused coalfield is being considered for lease to chicken farmers.

And while the area could become a public geo-park, turned over to both study and geology education, the leisure potential ranges from a very long zipwire, to mountain and quad biking, to redevelopment of the football pitch where the legendary Glenbuck Cherrypickers team played.

Scotland and Liverpool legend Bill Shankly was born in Glenbuck village in 1913, and was one of dozens of locals who went into professional football.

Although Glenbuck village has been flattened by the earthmovers, scores of fans still make the pilgrimage from Anfield to Shankly's birthplace each year.

If the Restoration Trust's plans work out, the pilgrims could have the opportunity to stay in holiday cottages and play on a restored Glenbuck pitch. The local mining heritage could be explained in a museum. Griggs is looking for the entrepreneurs to make it happen.

Healing scars

Along the valley and a rock's throw from the M74 motorway at the Happendon/Cairn Lodge services, Mainshill Wood opencast site offers more, highly unusual geological formations, where the pressures from millennia ago have left vertical coal and limestone seams.

The topography and location suggest this has more potential as a family-oriented leisure attraction, whereas Spireslack could work better for the committed thrill-seeker.

The ponds on the site are considered ripe for arrays of solar panels or (safety-conscious) leisure boating. As it currently stands, some of the site would work well as a science fiction film set.

According to Prof Griggs, local communities often see only vast scars on the landscape around them, and want them healed. He is encouraging them to see the sites as opportunities to make something out of the new contours of the land.

"I never thought I'd become one of Scotland's biggest landowners," he joked. "It's been great fun doing this. I've learned things. I think everyone should go through life and learn new things. I've met some fascinating people as I've gone through this, and I understand a bit more about geology now.

"But I'm sure the communities will say 'it's not fun having a big hole on my doorstep'. So my real fun will be when I get all the communities back to getting these sorted out for them".